About Auguste Comte

March 31, 2017

About William James

April 3, 2017Communism

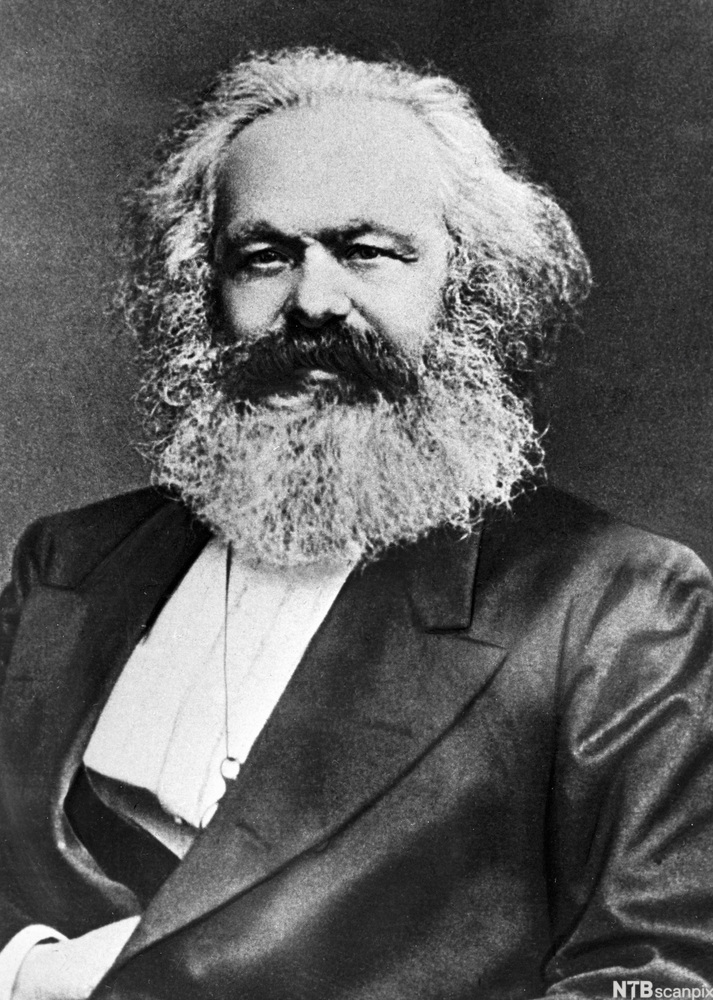

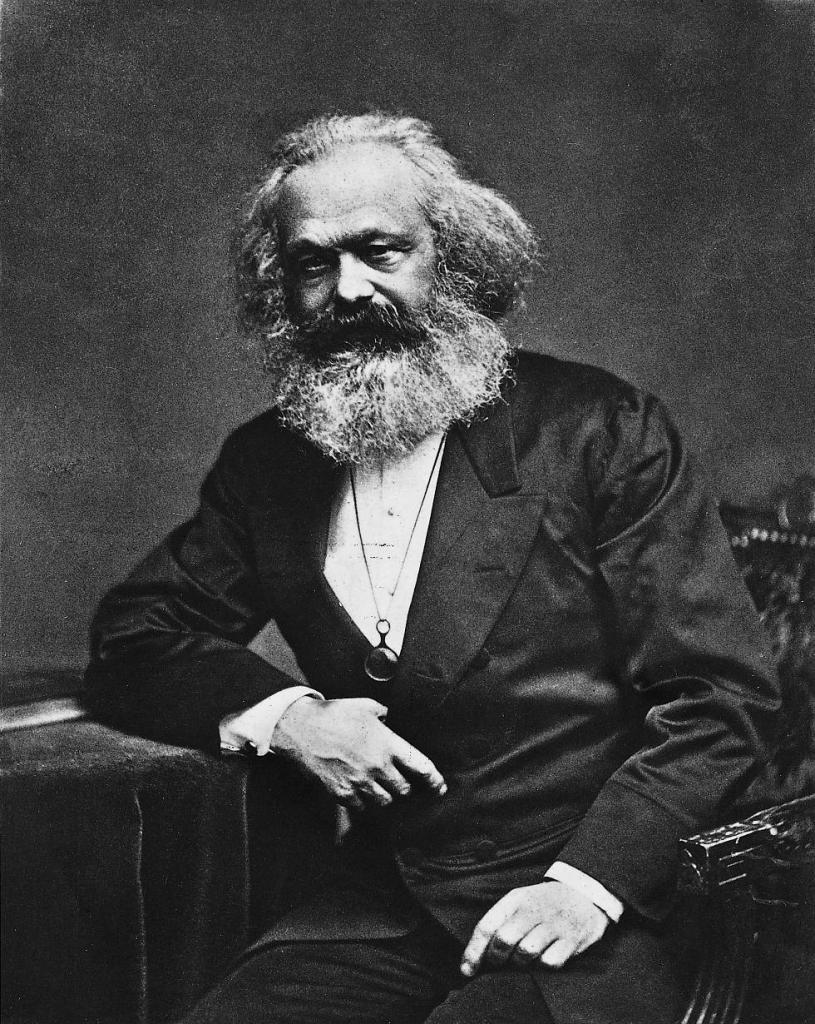

About Karl Marx

K arl Marx was the third child and eldest son of Heinrich Marx (born 1782), a lawyer of local distinction and moderate wealth who was appointed magistrate a year after formal conversion to the Evangelical Lutheran church in1817. The elder Marx combined enlightened Voltairean and deist inclinations with middle-class cultural interests, liberal Prussian patriotism, and a strong paternal affection for Karl. Both Heinrich and his Dutch wife, Henriette Pressburg, came from distinguished rabbinical families, Heinrich’s having been of particular prominence since the early fifteenth century in Germany Italy, and Poland, and Henriette’s for a century in Holland and before that in Hungray. Although there was no Jewish education or tradition in the upbringing of their children–indeed, the home was deliberately separated from family connections— Jewish self consciousness was to some extent unavoidable. There were nine children of whom four survived early childhood.

Marx was educated (1830–1835) at the Fried rich Wilhelm-Gymnasium in Trier, formerly a Jesu it school, where he was influenced chiefly by the headmaster, who was also the history teacher. But greater encouragement came from his father’s interest in the poet Gotthold Lessing and the French classics, and from their devoted neighbor, Baron Ludwig von Westphalen, who, with warmhearted-enthusiam, read Homer, Dante Cervantes, and Shakespeare as well as such advanced political thinkers as Saint-Simon, with young Marx. To his mother Karl was “the best and most beloved” and he wrote to his father of his “angel of a mother” despite the lack of any mutual intellectual or political sympathy. Heinrich Marx died in 1838, Henriette Marx in 1863

Biography

During 1835–1841, Marx studied at the Universities of Bonn and Berlin reading law at his father’s request but turning to philosophy and history. After initial resistance, he studied Hegel thoroughly, in part through the lectures of Eduard Gans but more deeply with an intellectual club of somewhat older philosophers among them Bruno Bauer and later Arnold Ruge. In 1836 Marx became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, daughter of his beloved older friends; they were married in 1843. Hoping for an academic career, he submitted a dissertation entitled “The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophies of Nature”to the University of Jena in 1841 and was awarded the doctorate. Central to that dissertation was Marx’s praise for Epicurus’s addition of spontaneity –the famous“swerve”to the determinism of the Democritean atomic dynamics, and for the Epicurean recognition of an animate level of human will along with the inanimate level of human will along with the inanimate mechanisms of natural necessity.

Immersed for some time in the history of philosophy Marx followed Hegel’s cultural setting of philosophical thought in an inherently rational and explicable sequence that is the historical as well as the systematic maturation of awareness and self awareness of the human spirit. The young Marx understood Hegel’s work to be also a fundamental advance in logic and methodology of inquiry, one that would enable philosophers to comprehend the movement of ideas in their actuality,their potentialities their mutual conflicts and inner tensions, and their syntheses. The scope of this outlook was vast, for it was to reach all the achievements of civilization with every specialty to be understood in its own historical development and in its relation to other; religions and philosophies but also the arts and literature fashions and superstitions, wars and revolutions, politics, jurisprudence, technologies, and the science of nature and of mankind. Above all, Marx thought that Hegel would make clear the relation of man to his environment, to his fellows, and to himself by a philosophy that was at once an epistemology, a history, and a psychology.

In contrast with the orthodox conservative reading of Hegel (according to which all that exists is to be understood by rational methods, and to be understood and defended as being rational, necessary, and good, the progressive embodiment of reason in history), Marx joined with the Young Hegelians in seeing basic challenge and change to be central for Hegel, with progress the recurring theme of the increasing self-awareness of human consciousness, in the larger society as much as in the philosophical mind. For young Marx the task of philosophical reason was to criticize whatever exists, whether in social institutions, religious doctrine, or the realm of ideas; for what exists is limited, always incompletely rational, and potentially open. Illusions, self-deceptions, group delusions, plain factual errors were to be exposed; the incompletely rational, the spurious, and the idolatrous would be recognized and, partly by being known, righted.

Not unexpectedly, the initial target of these young radical thinkers was religious doctrine, in its logic, its historical evidence, its social roles, and its relation to political interests and to scientific knowledge. Marx’s personal hero was Prometheus, “who stole fire from heaven and began to build houses and settle on earth .”Philosophy, for Marx,“turns itself against the world that it finds”.

If only on ideological grounds, Marx was unable to begin an academic career . His friend Bauer was dismissed from his teaching post at Bonn because of his secular critique of the Christian Gospels, and Marx, seeing his academic hopes disappearing, turned to journalism. He joined the staff of a liberal newspaper in Cologne, the Rhenished Zeitung; became editor by October 1842; and resigned early in 1843, just before the paper was closed by the Prussian censor. He met Friedrich Engels briefly in Cologne; and by their second meeting in Paris in 1844, a friendship had flourished that was to last until Marx’s death and to be an example of intimate collaboration, personal affection, steadfastness, and mutual respect.

Marx went to Paris in October 1843, already committed to a life that would combined sciencetific work with political activity. He had begun thorough studies of economics, in particular the writing of Adam Smith and Ricardo, and he was coming to terms with Hegelian and post-Hegelian philosophy. He joined the radical German colony in Paris, and collaborated in a short-lived publication. Arnold Ruge’s radical Deutsch französischre JahrbucherFor the first time Marx met revolutionary members of the urban working class; he knew the French socialist Prodhon the Germany poet Heine, and the Russian anarchist Bakunin; he associated himself with a secret communist group, the League of the Just; he became a socialist and a communist. He was in Paris for only three years but they were the years of his early maturity of his decisive intellectual professional and political transformation. From those years come his incisive and profound notebooks, published a century alter(the influential Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844) and his first writings with Engles.

Deported from France in 1845, Marx lived in Brussels until the revolutionary year of 1848 when he returned briefly to Paris at the invitation of the provisional government; he then went to Cologne to organize the Neue Rheinische Zeitung Within six months he had been charged with incitement to rebellion and tried in court Although acquitted in February 1849. Marx was expelled once more He stayed briefly in Paris was again ordered from France and in July 1849. settled himself and his family permanently in London Engles came to London in November of that year and in 1850 he settled in Manchester to work in his father textile firms thereby providing Marx, principal financial support.

Aside from some ten years writing political commentary mainly for the New York Tribune(1852–1862), Marx had no regular income. Despite Engle support he was often desperately poor and was beset by chronic and for extended periods very painful illnesses. In the 1860’s he wrote of the family’“humiliations torments and terrors”yet his three surviving daughters recalled with gratitude his unending story storytelling his games with them and his entrancing reading aloud from the whole of Homer, the Niebelungenlied Don Quixote the Arabian Nights and that Bible of the Marx household which was Shakespeare. 0nly in his last decade when Engele had retired from his prosperous business to settle in London was Marx somewhat free from financial trouble.

Marx’s political activities were manifold from his first contacts with working-class people in the early 1840’s his repeated organizational efforts; the German Communist League in Brussels (1847);various workers and democratic associations in subsequent years; the Manifesto of the Communist party written with Engles and published in 1848; the International Working Men’s Association of 1864 with its several congresses and its national section (ultimately dissolved in 1876 after a struggle with Bakunin); the uniting of the various German workers’; parties in 1875; continuing relations with the Chartists and with other British labor organizations efforts to assist refugees after the fall of Paris Commune in 1871; and throughout his life, a voluminous correspondence with European and American socialists and sympathetic thinkers and activists.

Nevertheless, Marx’s principal energies were devoted to his studies of empirical material and theoretical models relating to the development and functioning of modern European society, the political economy of capitalism. He saw the first volume of his chief work Das Kapital published in 1867; the second volume (1885) and the third (1894)were edited from Marx’s notes and drafts by Engels; further portions (1905–1910) were edited by Karl Kautsky. The important preparatory outlines and studies for Kapital the Grundrisse of 1857–1858 were first published at Moscow in 1939–1941 but became widely available only with the Berlin edition of 1953. Aside from these Marx’s works comprise more than a dozen monographs and treatises, and hundreds of shorter articles. Since 1957 the collected Marx-Engles Werke have appeared in forty volumes.

Marx and a science . Marx’s scientific work was entirely within the social sciences but on several counts his work related to the natural sciences.

First he sought to be scientific in his understanding of society. He gave recurrent attention to scientific methodology, at times in the context of comparing a natural science with social science but more often in his appreciative but critical fusion of Hegle’s mode of understanding with empirical studies or in his critical studies of the methods of classical political political economics. As general methodolgist of science, Marx is of historical and systeamatic interest beyond his great influence upon economis, history, and sociology.

Second Marx’s conception of explanation in social science was entirely historical with the consequence that he gave particular attention to the nature of historical understanding. Here again his methodological views are of broad interest, to the philosopher of science and to historians of ideas, as well as directly to the historian of science as historiographer, as specialist-investigator, and as historiographer, as sepcialist-investigator, and as the interpreter of science as a component of civilization.

Third, Marx’s central conception of natural science as a social phenomenon requires that historians and philosophers of science—and scientists—set their accounts of the cognitive as well as the practical character of science within the framework of an understanding of the societies within which science arises and develops. For Marx himself, as we shall see, this social character of science suggested an agenda of separate issues about the sciences. It required both a coherent Marxist history of science and technology, and the elaboration of a political economy of science, but Marx himself was unable to devote energy to these tasks.

Fourth, Marx’s materialist outlook upon mankind as situated within the natural environment, together with his conception of human emancipation through mastery of natural and social forces, bring his theory as well as in his epistemology and methodology. Here the relations between the Marxian dialectic, the Marxian understanding of materialism, and both of these with Marx’s concept of nature, take their place.

Science. The principal contribution of Karl Marx to the understanding of the sciences was his emphasis on their social character. Although he admired the great advances in knowledge that the sciences have provided, especially since the Renaissance—that is, he acknowledged the cognitive successes of the sciences–Marx nevertheless comprehended them as social phenomena. For the sciences to be social meant, to begin with, that they were part of the general social and economic processes of their times, changing with the changes in those historical processes; and if at times they were isolated from social forces, then they were understood as a product of social conflict and pressures that allow such isolation. To be social meant, further, to respond to socially produced motivations and purposes, and to do so with socially stimulated modes of inquiry and explanation, and criteria of success or failure.

At times a component of leisure-class playtime and the object of curiosity, and often characterized for many scientists by the pleasant fulfillment of creative labor rather than by the imposition of necessity, the sciences were nevertheless not in any full sense promoted by such pleasurable motivation, for in the development of the sciences Marx saw a central contribution to the grim and practical task of mastering nature. By the mid-nineteenth century, mastery had come to a novel and high point in human history, accompanied by the bourgeois revolution and the development of industrial capitalism. Where, Marx wrote,“…would natural science be without industry and commerce? Even this ’pure’ natural science is provided with an aim, as with its material, only through trade and industry, through the sensuous activity of men” (The German Ideology [New York ed.], 36).

As an element in the general historical process, science would be understood only in a completely historical way. Whether Hegelian or not in his historical epistemology, Marx imposed upon himself the task of comprehending scinece, like other human phenomena, within the political and economic history of mankind. Perhaps it is not evident that engineering, the technologies, and the practical arts must be described and understood in their social context and their historical development, with the external play of economic, military, political, cultural, and other forces upon them, as well as the internal sociology of inventivess, learning, and genius (these notions, too, would have to be investigated and supplemented, as well as set within historical contexts); but it was surely not so evident when Marx was writing. The noted pioneering works on the development of technology were Johann Beckmann’s Beiträge zur Geschichte der Erfindungen (5 vols. [Leipzig, 1782–1805]) and J. H. M. Poppe’s Geschichte der Technologie (3 vols. [Göttingen, 1807–1811]). Both were known to Marx, and neither paid much attention either to the steam engine in particular or to the industrial revolution at large. Even Charles Babbage limited himself to an analysis of individual technological accomplishments, rather than striving for general historical comprehension, in his standard work On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (London, 1832).

April Fools Day is coming. Prank your friends opening a never ending fake update screen on their computer. Sit back and watch their reaction.

The Marxian analysis is best seen in the detailed studies that constitute chapter 15,“Machinery and Modern Industry,” of volume I of Capital, particularly section 1, “The Development of Machinery.” Marx there sets himself the task of understanding the distinction between the two revolutions in mode of production: that of manufacture with labor power, which uses tools, and that of industrial production, which uses tools, and that of industrial production, which uses machinery. He sees the historical process to be from handicraftsmen who use tools to manufactures whose laborers are still craftsmen using tools to manufactures whose laborers are still craftsmen using tools but are socially linked through division of labor, with resulting reduction in labor cost. Then comes the drastically influential entry of machinery on the historical scene. His analysis may be given in several passages:

(1) On the general nature of productive machinery:

All fully developed machinery consists of three essentially different parts, the motor mechanism, the transmitting mechanism, and finally the tool or working-machine. The motor mechanism is that which puts the whole in motion. It either generates its own motive power, like the steam engine, the caloric engine, the electromagnetic machine, etc., or it receives its impulse from some already existing natural force, like the water-wheel from a head of water, the wind-mill from wind, etc.…The tool or working-machine is that part of the machinery with which the industrial revolution of the 18th century started. And to this day it constantly serves as such a starting point, whenever a handicraft, or a manufacture, is turned into an industry carried on by machinery (Capital, I, 367).

(2)On machines as distinct from human implements:

On a closer examination of the working-machine proper, we find in it, as a general rule, though often, no doubt, under very altered forms, the apparatus and tools used by the handicraftsman or manufacturing workman: with this difference, that instead of being human implements, they are the implements of a mechanism, or mechanical implements…. The machine proper is therefore a mechanism that, after being set in motion, performs with its tools the same operations that were formerly done by the workman with similar tools. Whether the motive power is derived from man, or from some other machine, makes no difference in this respect. From the moment that the tool proper is taken from man, and fitted into a mechanism, a machine takes the place of a mere implement. The difference strikes one at once, even in those cases where man himself continues to be the prime mover. The number of implements that he himself can use simultaneously is limited by the number of his own natural instruments of production, by the number of his bodily organs. In Germany, they tried at first to make one spinner work two spinning wheels, that is, to work simultaneously with both hands and both feet. This was too difficult. Later, a treadle spinning wheel with two spindles was invented, but adepts in spinning, who could spin two threads at once, were almost as scarce as two-headed men. The [spinning] Jenny, on the other hand, even at its birth, spun with 12–18 spindles, and the stocking-loom knits with many thousand needles at once. The number of tools that a machine can bring into play simultaneously, is from the very first emancipated from the organic limits that hedge in the tools of a handicraftsman…(Capital, 1,368, 370–371).

…apart from the fact that man is a very imperfect instrument for producing uniform continued motion but assuming that he is acting simply as a motor, that a machine has taken the place of his tool, it is evident that he can be replaced by natural forces…(capital, 1,370–371).

(3)On the change in scale of power required for industry:

Modern Industry had…itself to take in hand the machine, its characteristic instrument of production, and to construct machines by machines. It was not till it did this that it built up for itself a fitting technical foundation, and stood on its own feet…. But it was only during the decade preceding 1866, that the construction of railways and ocean steamers on a stupendous scale called into existence the cyclopean machines [steam engines] now employed in the construction of prime movers…capable of exerting any amount of force, and yet under perfect control.

…we find the manual implements reappearing, but [also] on a cyclopean scale. The operating part of the boring machine is an immense drill driven by a steamengine;…the tool of the shearing machine, which shears iron as easily as a tailor’s scissors cut cloth, is a monster pair of scissors; and the steam hammer works with an ordinary hammer head, but of such a weight that not Thor himself would wield it (capital, 1,373, 380–382).

(4) On the deliberate link of science with industry, and the social implication:

The implements of labour, in the form of machinery, necessitate the substitution of natural forces for human force, and the conscious application of science, instead of rule of thumb. In Manufacture, the organization of the social labour-process is purely subjective; it is a combination of detail labourers; [whereas] in its machinery system, Modern Industry has a productive organism that is purely objective, in which the labourer becomes a mere appendage to an already existing material condition of production. In simple cooperation, and even in that founded on division of labour, the suppression of the workman, isolated by the collective, still appears to be more or less accidental. Machinery, with a few exceptions to be mentioned later, operates only by means of associated labour, or labour in common. Hence the co-operative character of the labour-process is, in the latter case, a technical necessity dictated by the instrument of labour itself (Capital, 1,382).

(5) On the role of science in completing the role of the division of labor:

(a)…Intelligence in production expands in one direction, because it vanishes in many others. What is lost by the detail labourers, is concentrated in the capital that employs them. It is a result of the division of labour in manufactures, that the labourer is brought face to face with the intellectual potencies of the material process of production as the property of another, and as a ruling power. This separation begins in simple co-operation, where the capitalist represents, to the single workman, the oneness and the will of the associated labour. It is developed in manufacture, which cuts down the labourer into a detail labourer. It is completed in modern industry, which makes science a productive force distinct from labour and presses it into the service of capital (capital, 1,355).

(b) The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science into its paid wage labourers (Communist Manifesto, Collected Works, VI, 487).

(6) On the distinction between science and cooperative labor:

It should be noted that there is a difference between universal labour and co-operative labour…Universal labour is scientific labour, such as discoveries and inventions. This labour, such as discoveries and inventions. This labour is conditioned on the cooperation of living fellow-beings and on the labours of those who have gone before. Co-operative labour, on the other hand, is a direct co-operation of living individuals (Capital, III, 124).

(7) On the relations of nature, science, and industry:

…historiography pays regard to natural science only occasionally, as a factor of enlightenment, utility, and of some special great discoveries. But natural science has invaded and transformed human life all the more practically through the medium of industry; and has prepared human emancipation, although its immediate effect had to be the furthering of the de-humanization of man. Industry is the actual, historical relationship of nature, and therefore of natural science, to man…. In consequence, natural science will lose its abstractly material–or rather, its idealistic–tendency, and will become the basis of human science, as it has already become the basis of actual human life, albeit, in an estranged form. One basis for life and another basis for science is a priori a lie. The nature which develops in human history–the genesis of human society–is man’s real hence nature as it develops through industry, even though in an estranged form, is the true nature (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, 142–143).

Marx early recognized that, like prejudices and religious beliefs, ideas too have their social functions and determinants–and not least scientific ideas, even those of the most confirmed and objectively established sort. Thus, he was an admirer of Charles Darwin’s work, which he saw as a penetrating insight and proof of the historical character of biological nature. But he also noted, with amusement, that Darwin’s hypothesis saw nature in a social image:

(8) (a)…Darwin’s book is very important and serves me as a natural-scientific basis for the class struggle in history. One has to put up with the crude English method of development, of course. Despite all deficiencies, not only is the death-blow dealt here for the first time to “teleology” in the natural sciences but its rational meaning is empirically explained…(letter to Lassalle, 16 Jan. 1861, Selected Correspondence, Moscow ed., 151).

(b) It is remarkable how Darwin recognizes among beasts and plants his English society with its division of labour, competition, opening up of new markets, “inventions”, and the Malthusian“struggle for existence”. It is Hobbes’s bellum omnium contra omnes, and one is reminded of Hegel’s Phenomenology, where civil society is described as a “spiritual animal kingdom”, while in Darwin the animal kingdom figures as civil society…(letter to Engels, 18 June 1862, Seclected Correspondence, 156–157).

But Marx also saw Darwin’s work as suggestive for human history, and for the instrumental role of the human body, of technology, and of science:

(c) Darwin has interested us in the history of Nature’s Technology i.e., in the formation of the organs of plants and animals, which organs serve as instruments of production for sustaining life. Does not the history of the productive organs of man, of organs that are the material basis of all social organization, deserve equal attention? And would not such a history be easier to compile, since as Vico says, human history differs from natural history in this, that we have made the former, but not the latter? (Capital, 1,367).

To Marx, sociological understanding of the origin of scientific ideas was a component of the total appreciation of science. Two further aspects of his thought relate to such a historical sociology of science: the instrumental aspect of science, and of all knowledge, and the flexibility of nature when confronted with humankind. Here Marx consistently treated science under the general heading of labor, and he understood scientific conceptions to be joined with the material basis of human existence, with practical life, and with the social relations among human beings. The previous passage continues:

(d) Technology discloses man’s mode of dealing with Nature, the process of production by which he sustains his life, and thereby also lays bare the mode of formation of his social relations, and of the mental conceptions that flow from them….[But the] weak points in the abstract materialism of natural science, a materialism that excludes history and its process, are at once evident from the abstract and ideological conceptions of it spokesmen, whenever they venture beyond the bounds of their own speciality (Capital, 1, 367).

Marx saw that capital “first creates bourgeois society and [with it] the universal appropriation of nature….” Nature takes an instrumental role in human history.

(9) For the first time, nature becomes purely an object for humankind, purely a matter of utility; ceases to be recognized as a power for itself; and the theoretical discovery of its autonomous laws appears merely as a ruse so as to subjugate it under human needs, whether as an object of consumption or as a means of production (Grundrisse, 410).

Such an attitude toward technology and science leads to Marx’s notion of freedom, in the now familiar Marxian theme of reversing the domination of human beings either by the “blind” forces of nature or by the industrial society with its technology. It is technology that is the fundamental, because it is the mediation between man and nature:

(10)The realization of freedom consists in socialized man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their material interchange with nature and bringing it under their common control, instead of allowing it to rule them as a blind force (Capital, III, Chicago ed., 954).

This too leads beyond craft technology to science with the impressive modification of human life, which is made possible by the cognitive achievement of science when, and if, it is, in Marx’s term, “appropriated”:

(11) In this transformation, it is neither the direct human labour he himself performs, nor the time during which he works, but rather the appropriation of his own universal [scientific] productive power, his understanding of nature and his mastery over it by virtue of his presence as a social body–it is, in a word, the development of the social individual which appears as the great foundation-stone of production and of wealth (Grundrisse, 705, slightly modified).

To understand the “societal individual” is to understand Marx’s theory of society. Here we cannot pursue the main body of Marx’s work; but we must indicate his own method, which is also his conception of scientific explanation and scientific inquiry.

Scientific Method. Research into Marx’s methods of scientific thought and investigation, both as shown in his works and as deliberately expounded by him, has reached no general scholarly agreement. The principal explicit texts on method in Marx’s writings are section 3,“The Method of Political Economy,”of the introduction to his Grundrisse; Notes on Adolph Wagner: the preface to the second edition of Capital; section 2 of The Holy Family; and the preface to Critique of Political Economy.

Engels often praised Marx’s method, even above Marx’s achievements, which were said to have been due to it. In a letter of 1895 to Werner Sombart, Engels wrote:“Marx’s whole manner of conceiving things is not a doctrine, but a method. It offers no finished dogmas, but rather points of reference for further research, and the method of that research…”In the several methodological texts, and from his first writings to the last, Marx consciously worked on methodological problems, explicitly and repeatedly developing his own views by criticizing Hegel for methodological (as well as other) inadequacies; frequently criticizing other economists, historians, philosophers, and political thinkers on grounds of scientific method; and , at the same time, elucidating his own understanding of the conceptual principles of sound scientific thinking. Although much is still disputed among Marxists and by other students of Marx’s works, some matters of substance and of conceptual vocabulary seem clear from the relevant texts.

In the preface to the second edition of Capital, Marx quoted at length from a Russian article that treated his method in Capital in what Marx said was“this striking and generous way”:

(12) (a)“The one thing which is of moment to Marx, is to find the law of the phenomena…[and] the law of their variation, of their development, i.e., of their transition from one form into another…Marx only troubles himself about one thing; to show, by rigid scientific investigation, the necessity of successive determinate orders of social conditions, and to establish, as impartially as possible, the facts that serve him for fundamental starting points [and] both the necessity of the present order of things, and the necessity of another order into which the first must inevitably pass over…Marx treats the social movement as a process of natural history, governed by laws not only independent of human will, consciousness and intelligence, but rather, on the contrary, determining that will, consciousness and intelligence…not the idea, but the material phenomenon alone can serve as its starting-point. Such an inquiry will confine itself to the confrontation and the comparison of a fact, not with ideas, but with another fact. For this inquiry, the one thing of importance is both that facts be investigated as accurately as possible, and that they actually form, each with respect to the other, different moments of an evolution…it will be said, the general laws of economic life are one and the same, no matter whether they are applied to the present or the past. This Marx directly denies. According to him, such abstract laws do not exist. On the contrary, in his opinion every historical period has laws of its own….In a word, economic life offers us a phenomenon analogous to the history of evolution in other branches of biology. The old economists misunderstood the nature of economic laws when they likened them to the laws of physics and chemistry…” (Capital, 1, xxvii-xxix).

To this, Marx adds:

(12) (b)…what else is he picturing but the dialectic method? Of course the method of presentation must differ in form from that of inquiry. The latter has to appropriate the material in detail, to analyse its different forms of development, to trace out their inner connection. Only after this work is done, can the actual movement be adequately described. If this is done successfully, if the life of the subject-matter is ideally reflected as in a mirror, then it may appear as if we had before us a mere a priori construction (Capital, I,xxix-xxx).

Marx distinguishes the method of inquiry from the method of exposition. Inquiry (Forschung) is factually realistic, beginning with initially uninterpreted data that are subjected to analysis in stages of complexity that demand insightful abstraction, simplification, and subtlety. The factual data (Tatsache) are the concrete entities, or wholes; and the results of analysis are abstract principles, analyzed into theoretically formulated “parts,” hypothetically guided by theories that have been based upon, and more or less tested by, previous empirical investigations. Inquiry is a complex stage of empiricism and of inductive and hypothetical analysis.

Presentation (Darstellung) gives the results their necessary development, which aims to be a conceptual return to the concrete and brings the component parts or qualities of any subject matter together in their “organic” interrelatedness and their evolutionary or historical movements. The return will be mediated by expository as well as theoretical demands so as to clarify the separate qualities and the various relations among them and with their environment. For Marx, the truth will be the whole in its changes; and these in turn relate by historical processes, the Marxian dialectic of contending and negating “forces” within history. Indeed, the negative quality of historical changes links up, for Marx, with his positive notion of liberation of unfulfilled and repressed (alienated) human nature. (We shall see below how this may also comprehend nature.)

Volume I of Capital presents a theoretical model of the process of production in capitalism that, like so many models in natural science, isolates the theoretically conceived key qualities by means of simplifying assumptions. For Marx, abstraction was a justified but contrary-to-fact simplification. As he understood the problem of knowledge, scientific thought must be completed by a careful conceptual process of synthesis, by removal of the assumptions stage by stage, and by asymptotic approximation to the concrete complexity of the real world. The abstract model of Marx’s volume I was brought closer to the actual economic process of nineteenth-century capitalism, as he hoped, with his series of realistic considerations in volume III.

Abstraction is characteristic of all science but, for Marx, it has a central place in scientific investigation of social phenomena. Furthermore, abstraction is the method of discovering the “inner connections” and “inner movements” of the phenomena; Marx remarked that “all science would be superfluous if the manifest form and the essence of things directly coincided” (Capital, III, 797). In his preface to the first edition of Capital, Marx wrote:

…the body, as an organic whole, is more easy of study than are the cells of that body. In the analysis of economic forms, moreover, neither microscopes nor chemical reagents are of use. The force of abstraction must replace both. But in bourgeois society the commodity-form of the product of labour–or the value form of the commodity–is the economic cell-form (Capital, I, xvi).

Investigation, then, is empirical but also abstract; exposition is dialectical and concrete. Truth in science is concrete. And, as we shall see, Marx was not an inductivist. But while the scientist starts with abstract categories (of thought), he must go from these to the concrete, for the elementary and simple abstraction, although not fictitious, is only one aspect of any object of investigation, and an aspect in relation to man. To go further requires the human side and, hence, the social relations among the categories. Marx’s mature methodological reflections on this dialectic of abstract and concrete moments of scientific practice were most fully set forth in the 1857 introduction to the Grundrisse:

(13) It seems to be correct to begin with the real and the concrete, with the real precondition, thus to begin, in economics, with e.g. the population, which is the foundation and the subject of the entire social act of production. However, on closer examination this proves false. The population is an abstraction if I leave out, for example, the classes of which it is composed. These classes in turn are an empty phrase if I am not familiar with the elements on which they rest, e.g. wage labour capital, etc. These latter in turn presuppose exchange, division of labour, prices, etc. For example, capital is nothing without wage labour, without value, money, price, etc. Thus, if I were to begin with the population, this would be a chaotic representation [Vorstellung] of the whole, and I would then, by means of further determination, move analytically towards ever more simple concepts [Begriff], from the imagined concrete towards ever thinner abstractions until I had arrived at the simplest determinations. From there the journey would have to be retraced until I had finally arrived at the population again, but this time not as the chaotic conception of a whole, but as a rich totality of many determinations and relations.

…[This] is obviously the scientifically correct method. The concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many [abstract] determinations, hence a unity of the diverse. It appears in the process of thinking, therefore, as a process of concentration, as a result, not as a point of departure, even though it is the point of departure in reality and hence also the point of departure for observation [Anschauung] and conception. Along the first path the full conception was evaporated to yield an abstract determination; along the second, the abstract determinations lead towards a reproduction of the concrete by way of thought.

… it may be said that the simpler category can express the dominant relations of a less developed whole, or else those relations subordinate to a more developed whole which already had a historic existence before this whole developed in the direction expressed by a more concrete category. To that extent the path of abstract thought, rising from the simple to the combined, would correspond to the real historical process.

As a rule, the more general abstractions arise only in the midst of the richest possible concrete development, where one thing appears as common to many, to all. Then it ceases to be thinkable in a particular form alone…

This example of labour shows strikingly how even the most abstract categories, despite their validity precisely because of their abstractness-for all epochs, are nevertheless, in the specific character of this abstraction, themselves likewise a product of historic relations, and possess their full validity only for and within these relations.…

It would be unfeasible and wrong to let the economic categories follow one another in the same sequence as that in which they were historically decisive. Their sequence is determined, rather, by their relation to one another in modern bourgeois society, which is precisely the opposite of that which seems to be their natural order or which corresponds to historical development. The point is not the historic position of the economic relations in the succession of different forms of society. Even less is it their sequence “in the idea”(Proudhon) (a muddy notion of historic movement). Rather, their order within modern bourgeois society (Grundrisse, 100-108).

To Marx, exposition and articulation, when carefully accomplished, showed the movement of thought, a conceptual dynamic. He was concerned to contrast his understanding of this dialectic with that of Hegel, for whom

(14)… the life-process of the human brain, i.e., the process of thinking, under the name of “the Idea”, he even transforms into anindependent subject, [as] the demiurge of the real world, and the real world is only the external, phenomenal form of “the Idea” With me, on the contrary, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought (Capital, I,xxx).

For Marx, the concrete-in-thought was real and concrete enough, insofar as thoughts are real, but in no way was it to be considered as the genuine thing, as abstractions that somehow were formed into concrete matters of nature or society. Indeed, Marx focused his methodological criticism of Hegel in 1857 on this point:

(15) In this way Hegel fell into the illusion of conceiving the real as the product of thought concentrating itself [sich zusammenfassenden Denkens] probing its own depths, and unfolding itself out of itself, by itself, whereas the method of rising from the abstract to the concrete is only the way in which thought appropriates the concrete, reproduces it as the concrete in the mind. But this is by no means the process by which the concrete itself comes into being…the concrete totality is…a product…of the working up [Verarbeitung] of observation and conceptual representation into concepts [Begriffe]. The totality as it appears in the head, as a totality of thoughts, is a product of a thinking head, which appropriates the world in the only way it can, a way different from the artistic, religious, practical and mental appropriation of this world. The real subject-matter ratains its autonomous existence outside the head just as before: namely as long as the head’s conduct is merely speculative, merely theoretical. Hence, in the theoretical method, too, the subject, society, must always be kept in mind as the presupposition (Grundrisse, 101–102).

Marx’s empirical side had earlier been pressed against ‘Hegel in 1843 in the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’:

(16) Thus empirical actuality is admitted just as it is and is also said to be rational: but not rational because of its own reason, but because the empirical fact in its empirical existence has a significance [for Hegel] which is other than it itself. The fact, which is the starting point, is not conceived to be such but rather to be the mystical result.

It is evident that the true method is turned upside down. What is most simple is made most complex and vice versa. What should be the point of departure [of the presentation] becomes the mystical result, and what should be the rational result becomes the mystical point of departure (O’Malley ed., 9, 40).

The issue appears thirty years later in the 1873 preface, once more in Marx’s well-known image:

(17)…With him [dialectic] is standing on its head. It must be turned right side up again, if you would discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell (Capital, 1, xxx).

Perhaps the most explicit contrast, in Marx’s own estimation, was stated in the unpublished notes for The German Ideology:

(18) First Premises of Materialist Method.

The premises from which we begin are not arbitrary ones, not dogmas, but real premises from which abstraction can only be made in the imagination. They are the real individuals, their activity and the material conditions under which they live, both those which they find already existing and those produced by their activity. These premises can thus be verified in a purely empirical way…

Empirical observation must in each separate instance bring out empirically, and without any mystification and speculation, the connection of the social and political structure with production…

This method of approach is not devoid of premises…Its premises are men, not in any fantastic isolation and rigidity, but in their actual, empirically perceptible process of development under definite conditions.…

When reality is depicted, philosophy as an independent branch of knowledge loses its medium of existence. At the best its place can only be taken by a summing-up of the most general results, derived through abstractions which arise from the observation of the historical development of men. Vieweda part from real history, these abstractions have in themselves no value whatsoever. They can only serve to facilitate the arrangement of historical material, to indicate the sequence of its separate strata. But they by no means afford a recipe or schema, as does philosophy, for neatly trimming the epochs of history.… (German Ideology, 42,46–48).

Marx and Nature. By “nature” Marx meant the natural world of the nonliving, and the living, in which the human-social world was situated; but he also meant to include mankind within that natural world, as a species among the mammals, an animal among animals, a living being among all the forms of life, and a material entity of matter and energy, existing in the forms of space and time. In the profound but compressed manuscripts of 1844, Marx set forth his theme of understanding nature as that of understanding the relation between man and nature, between historical man and the external environment. But the environment comprises both the existing situation within which mankind exists, and as such relates to his species history, and also the autonomous world, temporally prior to mankind. What is this human-natural relation? In the long human history of recurring and potential scarcity, man has mainly struggled with nature. Whatever the cognitive forms–whether magical, technological, scientific, or otherwise–human interaction with nature has had domination as its goal. Even when the mode has been one of alliance or harmony with nature, nature has set the conditions and limits; and when the mode is one of successes in conquest, transformation, using and exploiting nature and natural processes, the transformations of nature by human labor (and its allied intelligence) nevertheless must be seen against the inexhaustible properties and impenetrable levels of resistance of matter.

For Marx, man and nature have a history together; man encounters nature in his own species history, each encounter within a specific concrete stage of that history. Without doubt, for Marx, nature had its own history; but that was not so much his own view as one he thought increasingly demonstrated by the natural sciences themselves. For him this was evident from developments in geology, astronomy, and, above all, evolutionary biology. And yet there was also a peculiarly Marxian understanding of nature that had two further aspects.

First, Marx stressed the insight that ideas of nature have their own history, which is a part of general human cultural history, itself a creative product of the material processes of society (and hence Marx’s apercu is a principal stimulant to later sociology of knowledge, and of scientific ideas in particular). Such a historical sociology of science reworked the ancient relativism about varying human perceptions of nature from skepticism about knowledge of nature to the (social-scientific) cognitive problem of the history of that knowledge. In the Marxian reconstruction of relativism it remains a difficult research question to locate the sources of success and failure of different approaches to nature, to ascertain the cognitive thread within human practice (and especially among the differing modes of cognitive practice that are revealed by studies in the history of the natural sciences and technologies). In the end, Marx believed practice was always the criterion, but practice is complex. At least, Marx saw, external nature was receptive to human labor, if not ever exactly a simple metaphorical raw and unformed clay to be shaped by the human potter. What was necessary in human development, he also saw, was for man to learn both the facts of natural entities, processes, tendencies, and laws, and the alternative possibilities to which those facts may be understood (with difficulty) as pointing. Here he thought he went beyond the “mere” empiricism of positive science.

In the latter sense, Marx understood the literal role of man within nature as concretely formative; men and women are fully natural beings who seek, choose, and remake the natural world, within the necessary limits. Man is child and maker of nature. Man the maker, for Marx, is even greater than his hero Prometheus, the conqueror of fire and liberator of mankind, because man creates new natural events, materials, qualities-indeed, creates a new nature.

The materialist history of ideas of nature is a history of changing intentional practice, for which implicit as well as explicit ideas have their several functions: cognition, rote aids to learning, conjectures to be tested and often to be generalized. All of this is articulated by means of the developing languages of collaborating scientific workers who are also ideological representatives of class and sectional interests (including interests in the concrete facts, in the truths of those facts and of what they suggest or conceal-or, at any rate, in some partial truths). Ideas of nature, and scientific theories as their modern form, were for Marx a part of the labor process, theoretical practice. To Marx, Hegel had investigated nature only through his logic, vainly seeking a concrete content; orthodox science investigated nature through observation and hypothesis, seeking autonomous laws; Marx investigated nature through man.

Second, at all human times, as nature is encountered historically, it must have its socially conditioned aspects and, increasingly, its socialized transformations. In its transition from the “natural” role of peasants in feudal agriculture to the “commodity” of man and natural processes in capitalist industry, nature changes. Nature has become, and now is, part of human history, which expands human nature so as to make over the external environment, at times, into the larger material body of individual men and of humanity. These metaphors were useful to Marx, to whom the flow of matter and energy between the body and the environment easily suggested that man is more than what his skin encloses, and for whom the social reality equally existed in such a mutual relationship with the natural context. Human bodily processes were natural, and so were social processes; Marx saw his most illuminating natural-science metaphor for social processes in“metabolism” (Stoffwechsel)

But the historical situation of nature was not seen by Marx as just metaphorical. Nature as known to concrete human beings is nature as it has been both dominated and understood; for nature to be under stood by ideas of nature means nature’s being subjected to the specific criteria and requirements of societies the dominant class forces of which have also dominated their forms of rationality. For Marx, while “prior” nature produces the human species in the course of biological, geological, and chemical processes, yet there are historical stages of nature, known to historians of science and technology by periods in the history of the natural sciences; and these, he anticipated, may be linked with the stages of evolution of social-economic formation. It is not too much to say, then, that there is a nature known to feudal society, and a different nature known to capitalist society; different societies raise different questions, work on different problems, use different ideas and methods, labor in different ways, learn differently, generalize differently, and reason differently. (When Marx wrote [see excerpt (5), above] that science is “pressed into the service of capital,” he did not refer to applied science alone.)

Marx’s early image of man in nature was that man appropriates nature, thereby bringing human purposes into nature. But which human purposes? Marx did not hesitate to link closely human appropriation and exploitation of nature with human exploitation of human beings. If men are treated as things, so will nature be; if human labor becomes the center of exploitation, and then is abstracted into average values for exchange in a commodity society–in a word, commercialized–then commercialized nature will appear (where it had not been); if men are distorted and polluted, then a polluted nature will be made. Marx’s conception of social tendencies toward the emancipation of mankind from human exploitation was explicit about his grounding of human liberation in a changing relationship with nature. Just as the emancipation of man requires emancipation from necessary labor (or at least minimization, as sketched in Capital, III), so it implies an open attitude on Marx’s part toward changes in ideas of nature when the relation of man to man is no longer dominated by exploitation.

In bourgeois industrial society, and always in class societies, Marx saw nature as a limiting and resisting material that had increasingly become a productive force; or if nature itself is not literally a productive force, then the social metaphor may be shifted and nature comes to function as abstract matter, to be made, administered, and exploited as men wish, and as abstractly as the labor power of the working men. In the expected future classless society, which Marx in the Grundrisse foresaw to be characterized by fully automated and nearly labor-free factory productive processes, human nature may once again see its (new) rationality within nature. That is, if human purpose transcends mere domination, then it may transcend that purpose with respect to external nature too; and nature again would be receptive.

Marx did not pursue the matter of nonexploited nature further, with the singular but crucial exception of the changes in human nature as part of the natural order. Any speculation or development of his suggestions is beyond our concern here, but at least his discussions of the bodily base for aesthetic sensibility may be mentioned. He linked liberation from domination by the social relations of private property to “the complete emancipation of all human senses and qualities” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, 139): indeed, the liberated human being in socialist society, the seemingly quite new man, would be one whose “senses are other than those of non-socialized man.” For, he argued, “…not only the five senses but also the so-called mental senses-the practical senses (will, love, etc.)-in a word, human sense-the human nature of the senses-comes to be by virtue of its object, by virtue of humanized nature. The forming of the five senses is a labor of the entire history of the world down to the present” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, 141).

At any rate, postcapitalist (or, in general terms, postexploitative) nature-for-man would be that part of the universe that is transformed into an environmental context within which the specifically human qualities and faculties will develop and flourish. Marx saw nature, and with it human nature, as flexible, plastic, and, above all, not restricted to a utilitarian function. He went so far as to say that the human senses would “relate themselves to the thing for the sake of the thing…” but he went on at once to add that “the thing itself is an objective human relation to itself and to man and vice versa…nature has lost its mere utility by use becoming human use” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, 139). These processes of humanization and socialization of natural objects are precise: “The eye has become a human eye, just as its object has become a social, human object-an object made by man for man.” And so sensuous human nature, along with all social-historically related external nature, changes as society does; Marx wrote: “The social reality of nature, and human natural sciences, or the natural science about man, are identical terms.”

The lesson was completely socialized. A repressive, exploitative society would be expected to produce a dehumanized nature, because the actual known world of science, technology, and their society is a world of things that, in Marx’s understanding of political economy, are actually or potentially objectified human labor. Through labor, the primary category of both his philosophy and his social science, we are brought to comprehend Marx’s natural science. Man makes himself, following Hegel’s famous phrase; but man also makes his natural world, for, as Marx said, nature is man’s inorganic body.

(19)…just as the working subject appears naturally as an individual, having a natural existence, so does the first objective condition of his labor appear as nature, as earth, as his inorganic body. The individual himself is not only the organic body of nature but also the Subject of this inorganic nature (Crundrisse,488).

In critical discussion of the destructive use of natural resources, Marx was looking ahead to a nondestructive relationship with nature, which equally would be the work of human labor; praxis, he believed, had the potentiality of treating human beings as human and, at the same time, of accepting both the potentialities and the limitations of nature. Within those potentialities, a fully human home on earth could be designed and constructed. in light of scientific understanding of the fullest range of human potentialities and those of external nature.

Marx took his idea of socialized nature cautiously. The limitations placed by autonomous nature are genuine, for, as mentioned above, Marx agreed with Giambattista Vico that human beings have made human history, but not natural history. The problem that arises, then, for Marx in his conception of nature can be clarified by his method of investigation: Nature in its autonomy, prior to human history and apart from that history, is, as one commentator remarked, only on the horizon of history. Nature has its own history, and yet it both generates and yields to the human species with its characteristically concrete history. Autonomous nature, then, is-and can be-only abstract for mankind because it has been apprehended neither by ordinary practice nor by any cognition through scientific practice. “…nature, taken abstractly, for itself, rigidly separated from man, is nothing for man” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, 117, Bottomore ed.).

There must be concrete nature rather than an artificial abstraction; but this shift to the concrete, as we have seen, is what Marx understands to be nature appropriated, exploited–indeed, mediated by socially organized labor. In 1880, toward the end of his life, Marx wrote: “Only a schoolmaster–professor [could construe] the relations of man to nature as not practical from the outset, that is relations established by action, but as theoretical relations…” (Notes on Adolph Wagner, 190). He went on to clarify: Not first the epistemological relation of scientific practice but, rather, first the socially primary relation of “appropriating certain things of the external world as the means for satisfying their own needs, etc.” and by “thus satisfying their needs, therefore they begin with production.” Intellectual practice–indeed, all learning from experience and reflecting upon experience in theoretical practice comes after the fundamental base within material production.

The common-sense Marx prevailed, even while he analyzed socialized nature and speculated upon liberated nature. In The German Ideology he wrote:

(20).…of course, in all of this, the priority of external nature remains unassailed…but this differentiation [between autonomous or presocial, and socially mediated, nature] has meaning only insofar as man is considered to be distinct from nature.

Marx goes on at once, in this comment on Feuerbach:

For that matter, nature, the nature that preceded human history…is nature which today no longer exists anywhere (except perhaps on a few Australian coral-islands of recent origin) and which, therefore, does not exist for Feuerbach (German Ideology, 63).

And yet, as we know from Marx’s sociological comment on Darwin’s work, any thought of nature before mankind, or of nature insofar as it is not yet known or appropriated, must, for Marx, be comprehended through the very same socially generated categories as the concretely grasped nature of ordinary labor and scientific practice. And even the autonomous qualities are suspected of being human-with cunning, as Hegel might have said (see excerpt [9] above).

If nature provides the metabolic biochemistry for man in society as in physiology, the metaphor deserves a further caution, since Marx understood that metabolism too has its autonomous properties and laws. Hence, “Man can only proceed in his production in the same way as nature itself, that is he can only alter the forms of the material” (Capital, 10). But these alterations affect nature too; Marx simply sees man as an agent of nature transforming itself. He speaks of labor power as a “material of nature transferred to a human organism” ; and he also sees quickly, in Capital, that the very simile of changing the forms of a kind of raw, unformed substance must be otherwise understood: “The object of labour can only become raw material when it has already undergone a change mediated through labour.” And yet it is nature that actually participates in such mediation through the emergence of the human species, which brings practical, creative, transformative labor into nature.

(21) Labour is, in the first place, a process in which both man and nature participate, and in which man of his own accord starts, regulates, and controls the material reactions between himself and Nature. He opposes himself to Nature as one of her own force…(Capital, I, ch. 7, 156).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. Original Works. The current standard ed. of the known published and unpublished writings of Marx and Engels in Marx-Engels Werke, 39 vols. plus index (Berlin, 1957–1968), which includes early works from student days, speeches and newspaper articles, and the correspondence with each other and with third parties. Supplementary vols. appeared in 1967 and 1969. There are two Russian-language eds. of the complete works, the Sochinenia, 25 vols.(Moscow, 1928–1946), and a 2nd, rev. ed. (Moscow, 1955-): a complete Oeuvres in French is under way (Paris, 1963-): and the Collected Works are in progress in English, 50 vols. plus an index vol. (New York-London-Moscow. 1974-). M. Rubel, Bibliographie des oeuvres de Karl Marx (Paris, 1956), is immensely helpful: it includes “Repertoire des oeuvres de Friedrich Engels” as an appendix: a supp. appeared later (Paris, 1960).

Also see M. Klein et al., Marx-Engels-Verzeichnis: Werke, Schriften, Artikel (Berlin, 1968). An earlier collected ed., the Karl Marx-Friedrich Engels: Historischkritische Gesamtausgabe, 11 vols. (Frankfurt-Berlin: Moscow, 1927–1935), commonly referred to as MEGA went only as far as 1848. Despite its limited scope, it was significant and influential as the first publication of major early writings of Marx and Engels and for the bulk of the correspondence between them. A guide to the various collected eds. is G. Hertel, Inhaltsvergleichregister der Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgaben (Berlin, 1957). As noted in these various eds. and guides, many of Marx’s works were first published decades after his death: the historically influential writings must be seen in that respect.

The principal centers of research in the original materials are the Institut fur Marxismus-Leninismus (Berlin). the Institute of Marxism-Leninism (Moscow), and the International Institute for Social History (Amsterdam). A practical introduction to the Amsterdam holdings is the Alphabetical Catalog of the Books and Pamphlets of the International Institute of Social History, 12 vols. (Boston, 1970); 2-vol. supp. (Boston, 1975). An annotated variorum scholarly ed. of the complete writings, speeches, notebooks, and correspondence of Marx and Engels is in preparation at the Berlin institute. A preliminary but useful specimen volume is Karl Marx-Friedrich Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Editionsgrundsätze und Probestucke (Berlin, 1972). Publication of this new MEGA began in 1975.

A chronological list of Marx’s principal works, as well as those written in collaboration with Engels. includes the following. The date of composition is indicated in parentheses.

“The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophies of Nature,” Ph. D. diss. (1841); Critique of Hegel’s ’Philosophy of Right’ (1843); On the Jewish Question (1843); Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844; The Holy Family (1844), written with Engels; Theses on Feuerbach (1845); The German Ideology (1845–1846), written with Engels; The Poverty of Philosophy (1847); Manifesto of the Communist Party (18480), written with Engels; The Class Struggles in France, 1848–1850 (1850; The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852): Grundrisse (Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy-Rough Draft) (1857–1858); A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1858–1859); Wages, Price and Profit (1865); Capital, written over many years; I was published in 1867; II and III were posthumously edited by Engels and published in 1885 and 1894: IV, Theories of Surplus Value, appeared in three parts, 1905–1910, and was edited by K. Kautsky; The Civil War in France (1871): Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875); and Notes on Adolph Wagner (1879–1880), unfinished critique of a textbook on political economy.

II. Secondary Literature. The literature Marx and his work seems endless. Of interest are the biographies, with differing viewpoints, by Franz Mehring (long a standard), Isaiah Berlin, Otto Rühle, Werner Blumenberg, H. Gemkow, David Riazanov, David McLellan, M. Rubel, and the exhaustive joint biographical studies of Marx and Engels by Auguste Cornu (treating only 1818–1846 in 3 vols. thus far). A detailed chronicle of Marx’s life, keyed to the current Werke ed., is M. Rubel, Marx-Chronik: Daten zu Leben und Werk (Munich, 1968), rev. trans. of the French original in Karl Marx, Oeuvres, Économie, I (Paris, 1965). A useful detailed chronological study of Marx’s life, with full précis of all his works, is given by M. Rubel in Marx Without Myth (Oxford-New York, 1975), written with M. Manale.

The topics that might be listed under “Marx and science” range throughout the entire Marx literature, for “science” in his case must include the various social sciences (not excluding historical studies) and their methodologies, along with the natural sciences, mathematics, logic, engineering, and the relevant portions of philosophy (including philosophy of science, metaphysics, and epistemology) as well as their histories. Thus, Marx’s methodology in Capital has been examined and interpreted; his relationship to Kant, to Spinoza, and to J. S. Mill; aspects of his critique and development of Hegel’s thought; his response to Darwin; his sociological and historical understanding of religions; and so on. The following list (see also “Engels” in the DSB) includes some works that bear upon Marx’s own understanding of nature, natural science, technology, methodology, and epistemology.

L. Althusser, For Marx (London-New York, 1969), translated from the French ed. (Paris, 1965): L. Althusser and E. Balibar, Reading Capital (London, 1970), translated from the French ed. (Paris, 1968); J. D. Bernal, Science in History (London, 1954; Cambridge, Mass., 1971); and The Freedom of Necessity (London, 1955); T. Carver, ed., and trans., Texts on Method of Karl Marx (Oxford, 1975), annotated texts of the introduction to the Grundrisse and the Notes on Adolph Wagner; J. Fallot, Marx et le machinisme (Paris, 1966); E. V. Ilyenkov, The Dialectic of Abstract and Concrete in Marx’s ’Capital’ (Moscow, 1960), in Russian-the third and central chapter is available in German in Beiträge zur marxistischen Erkenntnistheorie, A. Schmidt, ed. (Frankfurt, 1969), 87–127; in French in Recherches internationales (1968), 98–158; and in a complete Italian ed.; G. Lukacs, Zur Ontologie des gesellschaftlichen Seins: Die ontologischen Grundprinzipien von Marx (Frankfurt, 1972), a methodological study; H. Marcuse, Reason and Revolution (New York, 1941); S. Moscovici, Essai sur I’histoire humaine de la nature (Paris, 1968); B. Ollman, Alienation (Cambridge-New York, 1971); and M. Raphael, Theorie des geistigen Schaffens auf marxisticher Grundlage (Frankfurt, 1974), rev. ed. of Erkenntnistheorie der konkreten Dialektik (Paris, 1934)-available in English as vol. XLI of Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Boston-Dordrecht, 1978).

Also see R. Rosdolsky, Zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Marxschen ’Kapital’, 2 vols. (Frankfurt-Vienna, 1968), also in English (London, forthcoming 1978); N. Rosenberg, “Karl Marx on the Economic Role of Science,” in Journal of Political Economy,84 (1974), 713–728; “Science, Invention and Economic Growth,” ibid., 90–108, both in Rosenberg, Perspectives on Technology (Cambridge-New York, 1976); and “Marx as a Student of Technology,” in Monthly Review,28 (1976), 56–77; A. Schmidt, Der Begriff der Natur in der Lehre von Marx (Vienna, 1962; rev. ed., Frankfurt. ed., Frankfurt, 1971); also in English (London, 1971); A. Schmidt, Beiträge zur marxistischen Erkenntnistheorie (Frankfurt, 1969), esp. G. Markus, “Uber die erkenntnistheoretischen Ansichten des jungen Marx” J. Zelency, “Zum Wissenschaftsbegiff des dialektischen Materialismus” and E. V. Ilyenkov (cited above); P. Thomas. “Marx and Science,” in Political Studies,24 (1976), 1–23; R. C. Tucker, Philosophy and Myth in Karl Marx (Cambridge, 1961); and J. Zelency, Die Wissenschaftslogik bie Marx und ’Das Kapital’ (Berlin, 1968), trans. and rev. from the Czech ed. (Prague, 1962).