About Charles Robert Darwin

March 29, 2017

About Henri Bergson

March 29, 2017Evolutionary Naturalism

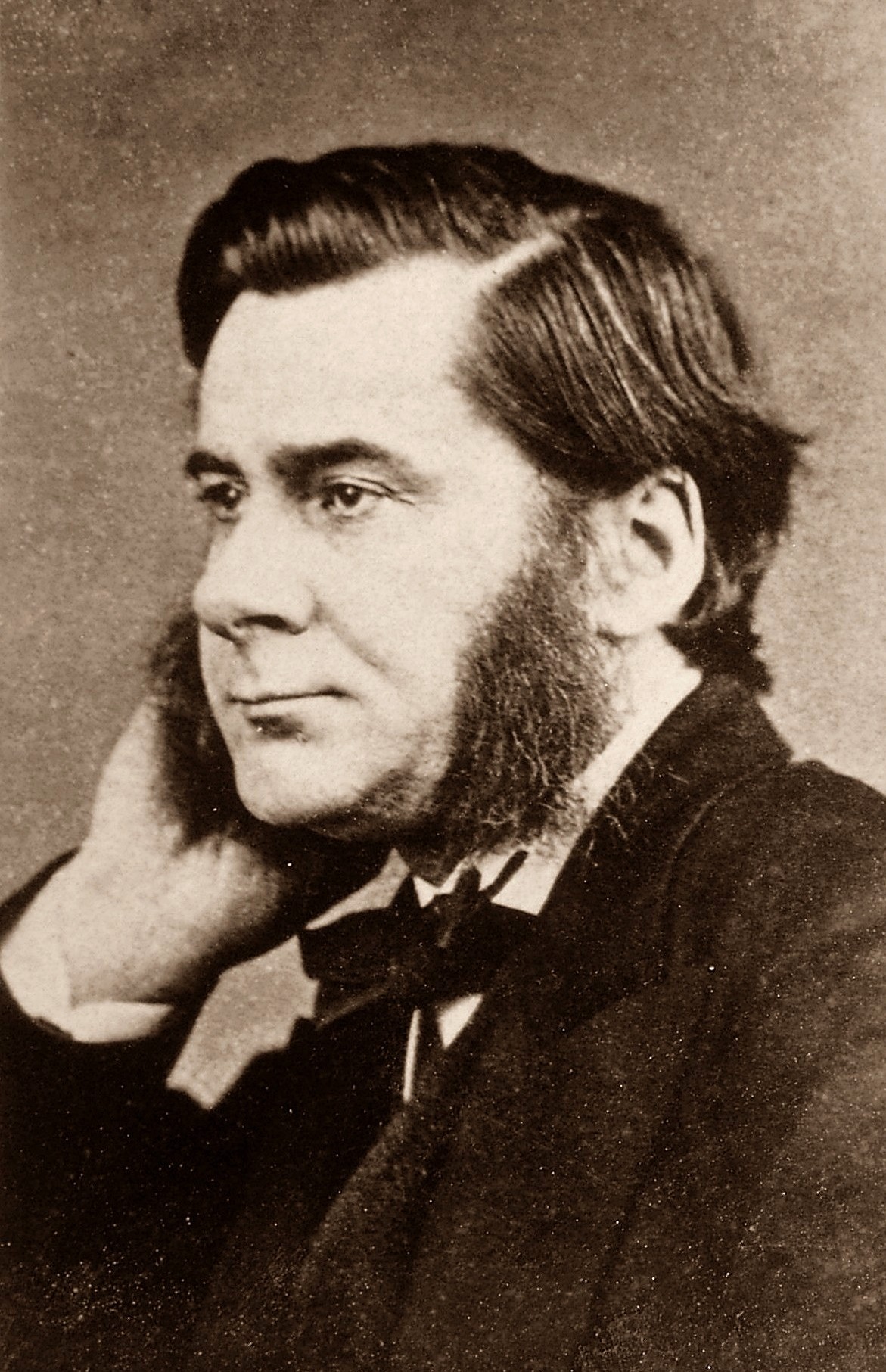

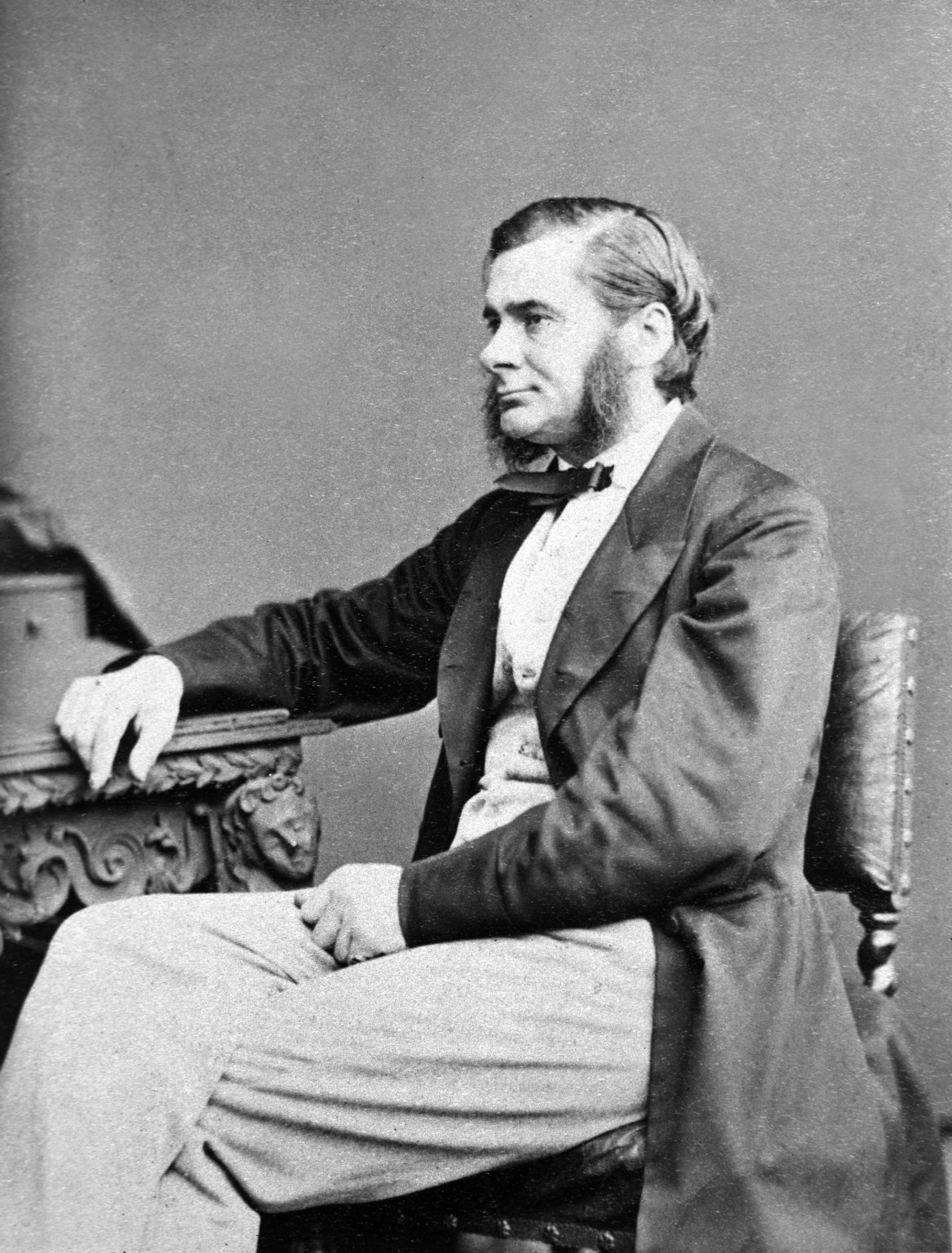

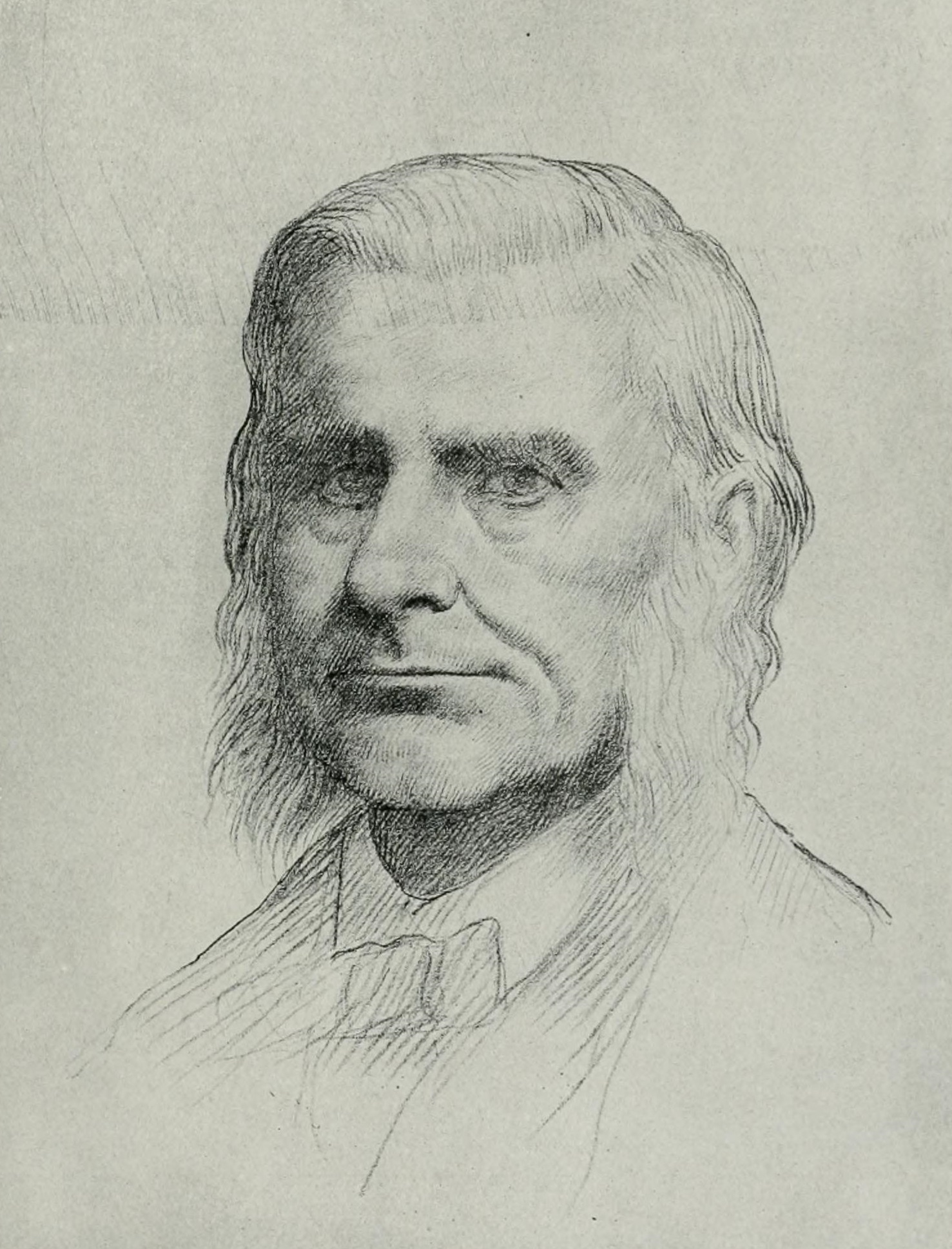

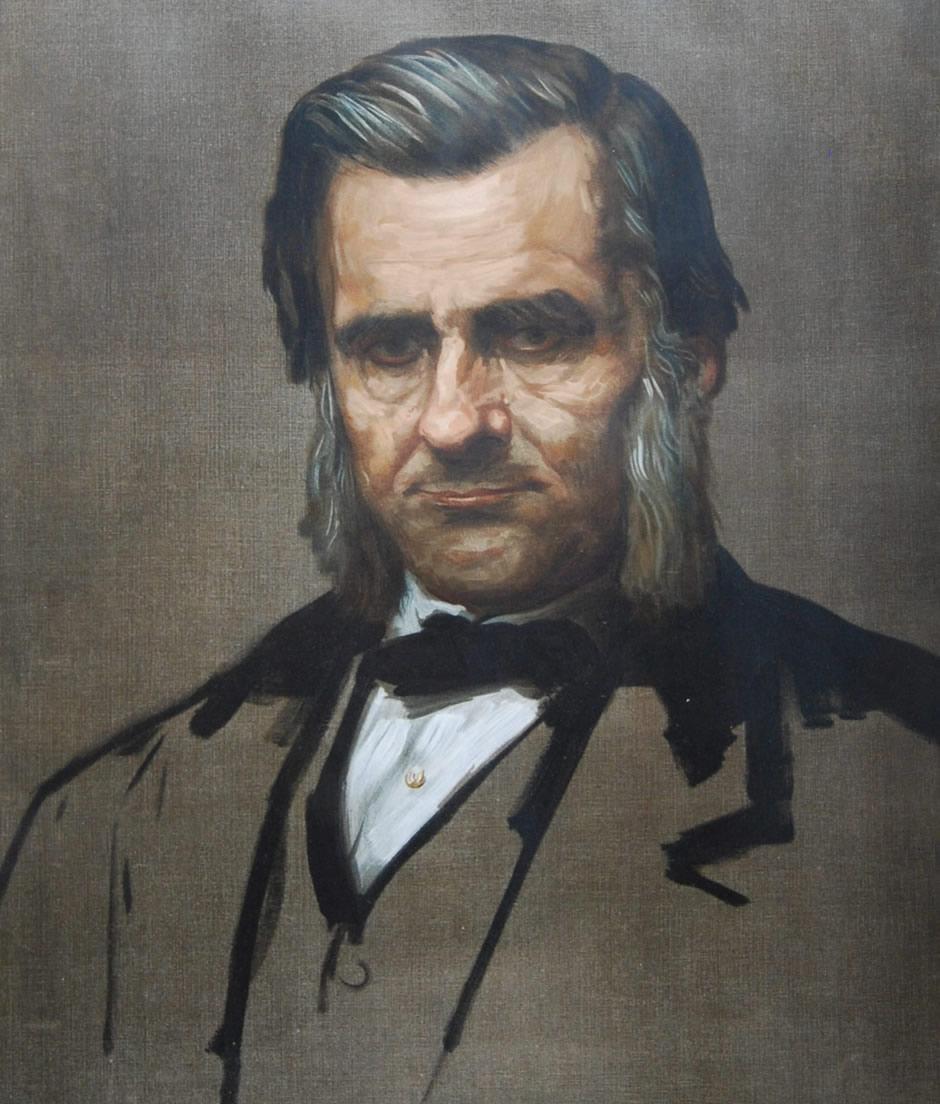

About Thomas Henry Huxley

T homas Henry Huxley, the distinguished zoologist and advocate of Darwinism, made several incursions into philosophy. From his youth he had studied its problems unsystematically; he had a way of going straight to the point in any discussion; and, judged by a literary standard, he was a great master of expository and argumentative prose. Apart from his special work in science, he had an important influence upon English thought through his numerous addresses and essays on the topics of science, philosophy, religion, and politics. Among the most important of his papers relevant here are those entitled 'The Physical Basis of Life' (1868), and 'On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata' (1874), along with a monograph on Hume (1879) and the Romanes lecture Ethics and Evolution (1893). Huxley is credited with the invention of the term 'agnosticism' to describe his philosophical position: it expresses his attitude towards certain traditional questions without giving any clear delimitation of the frontiers of the knowable. He regards consciousness as a collateral effect of certain physical causes, and only an effect--never also a cause. But, on the other hand, he holds that matter is only a symbol, and that all physical phenomena can be analyzed into states of consciousness. This leaves mental facts in the peculiar position of being collateral effects of something that, after all, is only a symbol for a mental fact; and the contradiction is left without remark.

His contributions to ethics are still more remarkable. In a paper entitled 'Science and Morals' (1888), he concluded that the safety of morality lay "in a real and living belief in that fixed order of nature which sends social disorganization on the track of immorality." His Romanes lecture reveals a different tone. In it the moral order is contrasted with the cosmic order; evolution shows constant struggle; instead of looking to it for moral guidance, he "repudiates the gladiatorial theory of existence." He saw that the facts of historical process did not constitute validity for moral conduct; and his plain language compelled other to see the same truth. But he exaggerated the opposition between them and did not leave room for the influence of moral ideas as a factor in the historical process.

Another man of science, William Kingdon Clifford, professor of mathematics in London, dealt in occasional essays with some central points in the theory of knowledge, ethics, and religion. In these essays he aimed at an interpretation of life in the light of the new science. There was insight as well as courage in all he wrote, and it was conveyed in a brilliant style. But his work was cut short by his early death in 1879, and his contributions to philosophy remain suggestions only.

Thomas Henry Huxley

was the seventh and youngest surviving child of George and Rachel Huxley. His father taught mathematics and was assistant headmaster at a school in Ealing which Thomas Henry attended for a brief period. The reguar instruction which Huxley received was minimal and lasted no more than two years. He was not considered a preecocious child but did exhibit in his yout the natural ability to draw which later, in spite of no training served him well in his zoological work. For his general education Hixley was largely self-taught; while still in his teens he read extensvely, particularly in science and mataphysics, and gained a facility in reading German and French.

Huxley had early leanings toward mechanical engineering as a career, but the combination of a family of moderate means and two medical brothers-in-law led him into medicine. He attended a postmortem when he was about fourteen and may have contracted some sort of dissection poisoning which manifested itself in an apathy remedied only by a stay in the open countryside. The “hypochondriacal dyspecsia” recurrent throughout the remainder of his life he thought to have been brought on by this incident; whatever it was, he was usually cured by a spell in fresh air. In 1841 Huxley became apprenticed to one of his brothers-in-law, John Godwin Scott, who practiced in the north London. During his apprenticeship, he wide reading, attended some courses, and earned the silver medal in a botanical competition.

In September 1842 Huxley and his brother James were awarded free scholarships at Charing Cross Hospital. The lecturer on physiology, Thomas Wharton Jones, had a strong influence on Huxley’s interest in physiology and anatomy and helped teach him methods of scientific investigation. Jones encouraged and aided Huxley with his frist scientific paper, on the discovery of a layer of cells (Huxley’s layer) directly within Henle’s layer in the root sheath of hair. Huxley passed the M.B. examination at London University in 1845 and soon afterward that for membership in the Royal College of Urgeons. He applied to and was taken into the Royal Navy, being assigned to H.M.S. Victory for service at Haslar Hospital, where he remained until assigned to H.M.S. Rattlesnake. on a surveying voyage to the Torres Straits off Australia as ship’s surgeon, not as a naturlist, a position filled by John MacGillivray. Any natural history Huxley undertook on the four-year voyage was his own affair, but it was to set the course of his career toward zoology rather than medicine. Abroad the Rattlesnake, Huxley’s scientific equipment was minimal, consitiing principally of a microscope and a makeshift collecting net. The limiatation of his equipment was perhaps fortuante, as he focused his attention on the wealth of planktonic life for the study of which a steady supply of fresh specimens was necessary. Through extensive shipboard dissections and through library work in Sydney, Australia (where he also saw much of William Macleay), Huxley was able to bring some order to these minute organisms which had been simply lumped together in those two great zoological lumber rooms, Linnaeus’ Vermes and Cuvier’s Radiata.

The novelty of much of his material was evident to Huxley and propted him to send several papers to the Linnean Society, about which he received on a major paper “On the Anatomy and the Affinities of the Family of the Medusae” to the Royal Society, which turned out to be the first of a series of wedges he drove into Cuvier’s Radiata. By the time of the Rattlesnake’s return the paper had been published in the Philosophical Transactions and soon earned him election as a fellow of the Royal Society. Combined with several other papers it brought Huxley the Royal Medal in 1852. After his return to England in 1850 Huxley arranged for leave from active duty in order to remain in London to work on the materials he had brought back. During these several years he became very much a part of the London scientific scene, making many friendships and enlisting the support of leading scientific figures in his running battle with the Admiralty over payment for the publication of his results. The battle continued until the Admiralty became exasperated and ordered Huxley back to active duty. He refused, leaving himself without any means of support and no prospect of a scientific appointment in London, where he felt he must remain to do effective scientific work. During this period he wrote articles and miscellaneous pieces for several reviews, when the editors would pay.

Invertebrate Studies . Nearly all of Huxley’s scientific effort in the period 1850-1854, during which he published about twenty scientific papers, was concentrated on the materials from the Rattlesnake. Working out the details and relationships of the delicate marine animals he studied set the pattern for his career and gave him a firm grasp of major zoological problems. of his numerous publications on these invertebrates his major contributions are found in four memoirs; his 1849 paper on the Medusae, two 1851 papers on tunicates, and one in 1853 on the Cephalous Mollusca. In his paper on the Medusae (Scientific Memoirs, I, 9-32), Huxley made two notable contributions—recognition of this group as a coherent whole and of an embryological analogy. First, he described the structure common to the different groups of Medusae, recognizing that they all consist fundamentally of two layers, or “foundation membranes’ which produce the inner and outer parts, that they all seem to lack blood and blood vessels, and that the existence of any nervous system was doubtful. He then allied with the Medusae the Hydroid and Sertularian polyps, whose structure is similarly based on the same two foundation membranes. Although it was less obvious, Huxley recognized that the complicated colonies (for example, the Portuguese man-of-war) making up the Physophoridae and Diphydae were colonies of hydralike organisms each of which had the typical Medusae double-membrance structure. The group of organisms which Huxley connected on the basis of this fundamental structure was readily accepted as one of the major groups of animals, becoming the nucleus of the Coelenterata, and as such required and received the attention of zoologists. Although its importance was perhaps not fully appreciated until after Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the embryological analogy that Huxley drew was an even more fundamental contribution than the organization of the medusoid organisms. He concluded that the two foundation membranes are physiologically analogous to the serous and mucous layers in a typical embryo. At this time Huxley made only the comparison and did not speculate on its possible significance.

In 1851 Huxley presented to the Royal Society two major papers on tunicates: “Observations on the Anatomy and Physiology of Salpa and Pyrosoma” and “Remarks Upon Appendicularia and Doliolum, Two Genera of Tunicates” (Scientific Memoirs, I, 38-68, 69-79). In the Salpa paper Huxley confirmed earlier suggestions that this organism’s life cycle passes through an alternation of solitary and chain-like colonial generations. Huxley observed a great abundance of specimens at various growth stages, from which he was able to come to the important conclusion that the solitary stage is the product of sexual generation and that the colony results from budding. This recognition contributed strongly to his theory of animal individuality in which he stated that both forms are parts or organs of a single individual, because they both develop from a single ovum. Huxley elaborated this thesis in a discourse “Upon Animal Individuality” at the Royal Institution in April 1852. He related, anatomically and systematically, all four genera of free-swimming forms covered in these two papers to the Ascidiacea, or sea squirts, and thus gathered the ascidians into a group based on their typical structure as he had done with the Medusae. The zoological position of Appendicularia had been most unsettled owing to its possession of a tail. Huxley demonstrated that this tail is a retained larval feature lost by most adult ascidians. The significance of this urochordal structure in relation to the vertebrate pedigree did not become evident until later.

Just as with the Medusae and the ascidians, Huxley sought and found in the Cephalous Mollusca a typical structure of which each genus and species is a modification. Briefly, Huxley started with several surface-dwelling forms with transparent shells and then dissected a wide variety of mollusks, determining their anatomical similarities on comparative grounds. Drawing heavily on the German embryologists who had studied their development, Huxley concluded that their parts are homologous and that they constitute a great group, the Cephalous Mollusca, comprising the Cephalopoda, Gasteropoda, and Lamellibranchiata all of which are modifications of a typical form, or “archetype.” The paper which resulted, “On the Morphology of the Cephalous Mollusca...” (Scientific Memoirs, I, 152-193), was highly important to his contemporaries for the anatomical and systematic conclusions which Huxley reached. It is also of particular interest for its insights into Huxley’s zoological methods, not only in his study of the invertebrates from the Rattlesnake but also in his later work on vertebrates, both fossil and recent.

Huxley opened his paper on the Cephalous Mollusca with a quotation from “the highest authority,” Richard Owen, setting forth what Huxley believed to be “the true aims of anatomical investigation.” In this passage Owen states that mere anatomical description is of relatively little value until the facts “have been made subservient to establishing general conclusions and laws of correlation, by which the judgment may be safely guided.” Whether with invertebrates, birds, the structure of the vertebrate skull, or fossil horses, Huxley sought to establish conclusions which, no matter how general or widesweeping, were invariably firmly based on facts from his experience. Huxley’s use of one of Owen’s favorite words, “archetype,” could lead to some confusion because of the naturphilosophisch and platonic connotations associated with it and because of his attitude toward the output of that mode of thinking, of which Owen’s work was a part. Huxley explicitly denied any connection between his archetypes and any ideas after which organisms might be modeled. To him the word meant “the conception of a form embodying the most general propositions that can be affirmed” about the organisms under consideration.

Within any great group, such as the Cephalous Mollusca, Huxley thought that the members varied by excess or defect of the parts of the archetype. He rejected the idea of any progression from a lower to a higher type within the group and instead thought there was “merely a more or less complete evolution of one type.” Here Huxley used “evolution” in its historic sense of an unfolding, or unrolling—that is, an embryological unfolding. While the manner in which he treated the Cephalous Mollusca was fundamentally the same as that used with the Medusae and ascidians, the discussion of the archetype and its modifications as a result of embryological development was a new element. There is more than a coincidental relationship between these ideas and those in the “Fragments Relating to Philosophical Zoology” which Huxley selected and translated from the works of Karl Ernst von Baer. Huxley had a broad acquaintance with the German zoological literature and held a high regard for much of it, especially in embryology and cytology; for example, see his major review “The Cell-Theory” (Scientific Memoirs, I, 241–278).

Vertebrate Studies. In 1854, when he succeeded Edward Forbes as lecturer in natural history at the Government School of Mines, Huxley at last had a means of support within the scientific community. Soon afterward he was appointed to the additional post of naturalist with the Geological Survey. He now had not only a scientific position but also the income needed to marry Henrietta Heathorn, whom he had met in 1847 in Sydney. They became engaged in 1849 but did not see each other again until she came to England for their marriage in 1855. Their son Leonard, the well-known teacher and writer, was the father of Julian Huxley, the biologist, Aldous Huxley, the writer, and Andrew Fielding Huxley, the physiologist.

At least in part, Huxley saw these positions as being temporary, while he awaited a post in physiology; since no such position became available, he held the same appointments for over thirty years. With considerable rapidity the focus of Huxley’s attention shifted from the invertebrates to the vertebrates. This shift was induced by his duties as lecturer on natural history, which required him to prepare in unfamiliar areas of biology, combined with his duties in connection with the Geological Survey, which brought him in close contact with a range of vertebrate fossils. Although beginning with a certain distaste for fossils, he soon became deeply involved in problems in paleontology and geology. His first fossil work was in cooperation with John William Salter, identifying a variety of fossils, an experience which was to prove invaluable in the aftermath of Darwin’s Origin. As with the invertebrates, Huxley was not concerned with species as such, but only as they led to more general zoological problems. In addition to his paleontological work, Huxley helped to organize the Museum of Practical Geology where he began, in 1855, his series of lectures of workingmen. He further developed his own regular course at the School of Mines. In addition to this he was appointed to the triennial Fullerian lectureship at the Royal Institution for 1856-1858. This sampling of his activities is indicative of the number of projects he would undertake at one time.

In the late 1850’s, Huxley began a detailed study of the embryology of the vertebrates, which provided a firm base for much later work as well as strengthening his teaching. An outcome of this study was his 1858 Croonian lecture at the Royal Society, “On the Theory of the Vertebrate Skull” (Scientific Memoirs, I, 538–606). Huxley made an important methodological contribution to morphology by his insistence that, as suggestive as they are, comparisons of adult structures are insufficient for the demon-stration of homologies. Only by studying the embryological development of the various structures from their earliest stages and determining that they follow the same path of development can we say with certainty that they are homologous. Huxley was continuing the tradition of K. E. Von Bear and M. H. Rathke and, more specifically, was reviving detailed studies of the skull done by Rathke and others in 1836-1839. These neglected earlier studies had shown the inadequacies of the vertebral theory of the skull originated by Goethe, elaborated by Lorenz Oken, and developed to its fullest by Richard Owen.

Huxley’s objective in his Croonian lecture was to put morphological studies on a more scientific basis, especially by the utilization of embryological criteria which could be as productive for the vertebrates as they had already been for the invertebrates. Many, and particularly Owen himself, saw this lecture as an attack on Owen, who was still considered England’s preeminent anatomist. Although not intended as such, it assuredly helped to prepare the way for the disputes between Huxley and Owen after 1859. In his lecture Huxley established that the various vertebrate skulls are modifications of the same basic type and, importantly, distinguished and named the different modes by which the lower jaw is articulated to the skull, which has become an important diagnostic character. Huxley concluded that the differentiation of the skull and the vertebral column occurs at such an early stage that they could not have a common origin. He also drew an analogy between the membranous, cartilaginous, and osseous stages of the development of the skull and between the skulls of Amphioxus, sharks, and the higher vertebrates.

The Evolution Controversy . Those today who know Huxley know him primarily as the protagonist of evolution in the controversies immediately following the publication of On the Origin of Species late in 1859. Huxley was prepared for the role he was to play, since he had by then acquired a broad background in vertebrate and invertebrate zoology and in paleontology. He also had read widely in the zoological literature in English, German, and French. Inevitably, he was familiar with the various hypotheses concerning the transmutation of species, particularly those of Lamarck and Robert Chambers, both of whom he held in low opinion. Huxley’s review of the 1854 edition of Chambers’ vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was the only one he later regretted for its “needless savagery.” Before the Origin, Huxley was constitutionally opposed to transmutation ideas because of his critical skepticism of all theories, the same skepticism which he embodied in the term he coined, “agnosticism.” Also, his belief that the natural groups of organisms were demarcated by sharp lines seemed, if valid, to negate the possibility of evolution occurring.

When the Origin was ready for publication, Darwin sent Huxley one of three prepublication copies, the other two going to Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker. Darwin was not confident that Huxley would react favorably to his book but wanted him as one of its judges. Darwin and Huxley had become by then close friends, and Darwin often had drawn on Huxley’s wide-ranging knowledge. On 23 November 1859 Huxley wrote to Darwin that nothing had impressed him more since his reading of Baer, praised Darwin for his new views, and warned him about the abuse he was bound to receive. Already Huxley was sharpening his claws and beak in preparation for the impending battles. Entirely by chance, Huxley had an early opportunity to praise the Origin publicly, although anonymously, when he was asked to review it for the London Times (26 December 1859). Huxley followed this with a Friday evening discourse at the Royal Institution in February 1860 and an article in the April issue of the Westminster Review. His February discourse “On Species and Races, and their Origin” (Scientific Memoirs, II, 388-394) set a model for many later defenses of the Origin. After discussing the varieties and species of horses and pigeons, Huxley turned to man’s relation to the apes, the topic of greatest concern to his listeners and one only hinted at in the Origin. Without going into the full details, he argued that man differs less from the highest members of the Quadrumana than the extreme members of that group differed from one another. This was an implicit rejection of Owen’s classification of the Mammalia. Moreover, and most importantly, Huxley made a strong plea, often to be repeated, for judging Darwin’s work on scientific grounds, as a work in science, for “the man of science is the sworn interpreter of nature in the highest court of reason”.

When the British Association for the Advancement of Science met in Oxford late in June 1860, Huxley was recognized as an able younger biologist, but his name certainly was not yet a household word. During this meeting he had two encounters important for the future of Darwin’s hypothesis, as well as for his own career: one with Owen on scientific details, which was settled later, and one with Samuel Wilberorece, bishop of Oxord, which was of a more general nature. The result was Huxley’s being recognized as the principal defender of the Origin and he thus earned the name “Darwin’s bulldog.” The less prolonged, although more dramatic, of these was the second, the exchanges with “Soapy Sam” Wilberforce. Wilberforce had been coached in matters scientific of Owen, but he was apparently a poor learner-or Owen a poor teacher. Wilberforce made a number of scientific blunders and then directed his famous query to Huxley asking whether Huxley’s ancestry from an ape was on his grandfather’s or his grandmother’s side. Waiting until the audience called upon him to answer, Huxley carefully corrected the Bishop’s scientific errors and added that he would rather be related to an ape than to a man of ability and position who used his brains to prevent the truth. Unfortunately, there is no verbatim account of this incident, but a number of eyewitness accounts agree in substance. This episode, in addition to establishing Huxley as the principle spokesman for Darwin, gave convincing evidence that the evolutionists were not going to be cowed by the Church.

Huxley’s dispute with Owen

at the British association meeting had actually begun in 1857 and was not settled finally until 1863. In 1857 Owen read before the Linnean Sociaty a paper on the classification of the Mammalia, which he repeated substantially in his Reade lecture at Cambridge in MAy 1859. Cuvier had seperated man, in the order Biman, from the remainder of the primates in the order Quadrumana. Owen constructed a taxonomy based on certain characteristics of the mammalian brain, which seperated man still further from the other primates and placed him in a new subclass, the Archencephala. In his system Owen argued that the human brain differed fro mthose of all other mammals not only in degree but also in kind, and that it had certain structural characters peculiar to it. The most famous of these was a small internal ridge known as the hippocampus minor which became well-known to the public and gave its name to this controversy. The essential factor in Owen’s taxonomy of the MAmmalia wasthe assertion that man was zoologically distinct from all of the other mammals. After the Origin, Owen’s system carried the additional implication that an evolutionary hypothesis valid for the other animals would not necessarily apply to man. When, in 1857, Huxley had first become acquainted with Owen’s classification of the Mammalia he doubted Owen’s facts and conclusions regarding man’s place in nature. Characteristically, Huxley performed a series of dissections of primate brains to satisfy himself that Owen’s qualitative distinctions were not valid. Although Huxley published nothing on the brain at that time, he incorporated the information in his teaching after 1858, and it provided him with the necessary ammunition for the British Association meeting in 1860. On Thursday, 28 June, in section D, after a paper on plants by Charles Daubeny, Owen repeated his assertions of 1857 and 1859 that the brain of the gorilla, when compared with that of man, showed greater differences than existed between that of the gorilla and of the lowest of the Quadrumana, or primates. To this assertion Huxley publicly gave a “direct and unqualified contradiction” and promised to justify himself in this unusual procedure elsewhere. This he did in “On the Zoological Relations of Man With the Lower Animals” (Natural History Review, 1 [1861], 67-84), in which he demonstrated through references to a series of earlier studies by various authors the falsity of Owen’s assertions that only in man did the celebral hemispheres overlap the cerebellum and that only man possessed a posterior cornu of the lateral ventricle and a hippocampus minor. The above article wa part of an extended debate with Owen (1860-1863), in which Huxley, with assistance from others and particularly from William Henry Flower’s dissections, effectively showed Owen’s errors regarding those cerebral characters.

By the end Huxley had demonstrated clearly that the differences between man and the apes were smaller than those between the apes and the lower primates. Therefore, man had to be considered zoologically a member of the primates. While the controversy was based on certain rather esoteric anatomical details, the results of the hippocampus minor debate were reported in the public press, inspired poetry and cartoons in Punch, and occupied a prominent place in Charles Kingsley’s novel The Water Babies.

Darwin had said in the Origin only that light would be thrown on man’s relationship to his evolutionary hypothesis, and this controversy, with its public following, was instrumental in man’s being considered in zoological terms and his orgin as a result of the evolutionary process. Huxley also covered much of the same material on man and the other primates in lectures to various audiences and in his Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863), which synthesized the anatomical and embryological evidence from his own work and the literature.

In addition, during the 1860’s, Huxley devoted a fair share of his effort to physical anthropology, particularly on the recently discovered Neanderthal skull and various races of aman and their relationships to one another. Huxley’s treatment of man in zoological terms, as a topic to be considered scientifically and not emotionally, assisted strategically in the public’s considering Darwin’s evolutionary hypothesis on the same terms. This latter was Huxley’s goal in all of his lecturing and writing on the subject of evolution. He firmly believed that if people would only look at the alternative in a cool and reasoning manner they must recognize the fact of evolution and natural selection as its most probable mechanism.

While Huxley is best known for his defense of Darwin’s hypothesis, he did not accept it uncritically and did not consider that the problem was finally settled nor that natural selection was by any means proven as the mechanism. When Huxley read the Origin, he was immediately convinced of the fact of evolution and thought Darwin had successfully put this ancient doctrine on a scientific basis. Huxley had long been handling the kinds of evidence that Darwin used and was well acquainted with them; he needed only for Darwin to lead the way in showing him how to arrange it. That way led through natural selection as the mechanism by which evolution had occurred. For Huxley and others natural selection provided a method for organizing their own facts. Throughout his life after 1959 Huxley maintained that natural selection was the most probable hypothesis of an evolutionary mechanism. For him it remained a hypothesis because of the lack of experimental proof. Huxley thought this proof would be the “production of mutually more or less infertile breeds from a common stock” in a selective breeding program. He thought it could be achieved “in a comparatively few years.” In 1893 Huxley still thought such proof was necessary, but he was less optimistic about the time required. In his early essays on evolution, which he would stand by until the end of his life, he distingiuished between morphological species, which could be demonstrated and could serve as evidence that evolution had taken place, and physiological species, which must be produced by selection to confirm natural selection as the mechanism.

After 1859 Huxley’s own scientific work, as distinct from his role as Darwin’s defender, had much the same charater as his earlier work, with the notable difference that it was now focused principally on vertebrates, both recent and fossil. A considerable proportion of this activity was detailed, descriptive work on a single narrow problem in anatomy or paleontology—the “species work” which was always a burden to him. In several areas, however, Huxley made the same kind of broad, sysnthetic contributions he had made on invertebrates—"the architectural and engineering part of the business,” as he called it. Huxley substantially groups, basing his revisions on his own observations, to which he added a broad knowledge of the relevant literature. This aspect of his work has been of value not because all of it is still considered valid, but because it posed questions and problems which stimuilated further work by his followers, who, expectedly, went beyond Huxley.

Huxley did important work on all the major groups of vertebrates; but during the 1860’s he was particularly interested in birds. After his Croonian lecture he began to study the develpment of the chick’s skull. Approaching the birds as if they were all fossils, Huxley based his classification on osteological characters in what was probably the first comprehensive, comparative study (1867) of a single avian organ system (Scientific Memoirs, II, 238-297). His study set a model for much later avian taxanomic work which incorporated Huxley’s findings. On the basis of several skeletal characters, for example, the keel and ossification of the sternum, Huxley divided the birds into three principal groups, Saurarae, Ratitae, and Carinatae, the subdivisions of which were based heavily on the bony structure of the palate. In 1868, in a memoir on the anatomy of the gallinaceous birds (Scientific Memoirs, II, 346-373), Huxley, building particularly on P. L. Sclater and Darwin, incorporated the facts of geographical distribution into his taxonomy, making zoo geography a part of the definition of a species. He also suggested a linking of South America and Australia, a suggestion which has since received much support.

Paleontology. Some of Huxley’s earliest paleontological work was on fishes from the Devonian Downton Sandstones which led him into a revision of much Devonian fish material and a memoir (1861) on the classification of the Devonian fishes (Scientific Memoirs, II, 421-460). Huxley was able to throw new light on many affinities, revising the work of Louis Agassiz and other early workers, by utilizing the new and also the results of his extensive studies of piscine embryology. This memoir, and his 1866 supplement, remained a standard work on these animals for several decades. Huxley also did extensive studies of labyrinthodont Amphibia from the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian of Great Britain and similar forms from around the world (see Scientific Memoirs, II-III, Passim). The most important of these were the genera Loxomma and Anthracosaurus. His elaboration of the morphology of these early tetrapods led him to place them on the borderline between the fishes, amphibians, and reptiles. Their ancestral relationship to all higher tetrapods has since been well organized.

Closely related to his studies of birds was Huxley’s interest in Mesozoic reptiles, particularly the Dinosauria. He rejected the proposed close affinity of pterodactyls to birds, the similarities being only analogous and not homologous. Huxley recognized that all the Dinosauria he had examined had strong ornithic characters in the tetraradiate arrangement of the ilium, ischium, pubis, and the demur, factors by which they differ from the majority of reptiles (see for example, Scientific Memoirs, III, 465-486). At about the same time E. D. Cope recognized similar relationships. For these reptiles Huxley established (1869) the order Ornithoscelida (most of the members of which are now in the order Ornithischia), which included such forms as the Iguanodon (Scientifice Memoirs, III, 487-509). On the basis of these specific similarities and more general evidence Huxley combined the reptiles and birds into the Sauropsida, one of his three great divisions of the Vertebrate; the others were the Ichthyopsida (fishes and amphibians) and Mammalia. He later (1880) further divided the Mammalia into three groups of ascending complexity, the Prototheria (monotremes), Metatheria (maruspials), and Eutheria (placentals). These terms were meant to describe “stages of evolution” and, therefore, were more than purely taxonomic terms (Scientific Memoirs, IV, 457-472). These became important divisions because they were based on deepseated anatomical characters, rather than the relatively superficial ones, such as teeth and digits, which are more closely related to the mammals’ life habits.

In 1862 huxley, as secretary of the Geological Society, was called upon to give the presidential address, in which he discussed several aspects of paleontology. He did not think that the fossil record had been able to provide evidences that modifications of any group had actually taken place through geological time or that earlier members of any long-standing group were more generalized than later ones. Eight years later, when Huxley was president of the Geological Society, he felt compelled to correct the statements of the earlier address. In the interim a substantial quantity of fossils had been discovered, among which were a number of ancestral forms of horses. From European Middle Miocene deposits came a three-toed equine, Anhitherium, which Huxley connected by stages to Equus, each member of the sequence being the result of increased specialization away from the average ungulate mammal. Huxley thought there should be Eocene predecessors of Anchitherium which were even less modified, and he suggested Plagiolophus might nearly be this form. He thought the equine pedigree would eventually be stretched back to a five-toed ancestor. One of Huxley’s first visits on his American trip in 1876 was to Othniel Charles Marsh in New Haven, where he spent most of a week studying Marsh’s very complete series of North American fossil horses extending back to the Upeer Eocene Orohippus. Huxley recognized this as a more complete and more extensive series insights and fossils, rejected his proposed line of equine ancestry and revised an address to be given in New York. In that lecture, primarily using sequences of teeth and limb material, Huxley presented the most complete evidence of modification having occurred through geological history. He then went on to predict that a yet more generalized form than Orohippus would be found; two months later he received work that Marsh had found Eohippus, the proposed ancestral form. This series of horses was the first extensive series which gave proof that the kinds of modifications demanded by Darwin’s hypothesis had taken place and that the ancestral stages were more generalized than their more recent representatives.

Influence in Scientific Education. In addition to his extensive scientific output, of which only some high spots have been touched here, Huxley was an active teacher from 1854 until near the end of his life. Although it changed and developed under him, the lectureship on natural history at the Government School of Mines moved from Jermyn Street to South Kensington in 1872, to become part of the Royal College of Science, Huxley was forced to give a lecture course supplemented only by demonstrations, owing to an absence of laboratory space. After 1872 laboratory work became an integral part of his course, in which the students did the dissecting and observing to verify the facts in the text and lectures. Huxley conceived of this as an essential training in scientific method. He was fortunate in having Michael Foster and E. Ray Lankester among his first laboratory assistants. Both his lectures and laboratory classes were based on the same basic notion types that he used in his original scientific work; Huxley thought this was the only means of bringing any logic to the myriad organic forms. In this approach to biology, Huxley was highly innovative, as he well aware, although his method of teaching has now become a commonplace.

Huxley’s teaching was by no means limited to his formal courses. He was Fullerian professor at the Royal Institution and Hunterian professor at the Royal College of Surgeons. He also gave a number of Friday evening discourses at the Royal Institution and a considerable array of special lectures on assorted topics at various locations. of all his public speaking Huxley was most interested in the serious of workingmen’s lectures which gave regularly, beginning in 1855, by which he wanted “the working classes to understand that Science and her ways are great facts for them.” He was “sick of the dilettante middle class” and wanted to try his skills with the working class, who turned out in large numbers for his appearance. Huxley did not talk down to his audiences bacause of a firm belief that even the most complicated ideas could be understood by the major-ity of mankind if they were presented clearly and logically, step by step. Some of Huxley’s fines addresses were to workingmen, for example, the series on man’s place in nature and his 1868 “On a Piece of Chalk” (Collected Essay, VIII, 1–36). The latter is an excellent example of his style, which was at the root of his great success as teacher and public speaker. This style was not dependent on the use of words or the structure of sentences but on the careful organization of ideas. Huxley;s stress on clarity of thought was equally evident in the full range of his writings and was a key to their success.

In many places Huxley stressed the need for inclusion of science at all levels of education; but he did not stress science to the exclusion of history, literature, and the arts. His view of education not as an accumulation of facts but as a training and honing of all the faculties an individual might possess was the key to his conception of a liberal education. Huxley made a case for his views to various audiences: at the South London Working Men’s College in “A Liberal Education; and Where to Find It”; at the opening of The Johns Hopkins Univeristy in “Address on University Education”; and on the eve of his election to the first London School Board in “The School Boards: What They Can Do, and What They May Do” (all in Collected Essays, III). The last outlines the program which to great extent Huxley convinced his fellow board members to adopt under the 1870 Act of Parliament. He included the necessary disciplines of reading, writing, and arithmetic, and added physical science, drawing singing, physical development, and domestic subjects. Surprisingly, to many of his colleagues, he also advocated studying the Bible, but without any theology, because it was great literature which embodied great morality and was the basis of three centuries of British civilization. In his service on the London School Board, Huxley proved to be one of the important shapers of primary education.

As offshoots of his teaching and often based on his lecture series, Huxley wrote several textbooks; two were designed for the general public. Physiography (1877) was an introduction to nature in all its aspects, what might be called general science, and Lessons in Elementary Physiology (1866) was a discussion of the human system written for the schools. For anatomy students Huxley wrote The Crayfish (1879) as an introduction to zoology and general works on both vertebrate and invertebrate animals.

Huxley’s philosophic interests and writings focused on Descartes, Berkely, and Hume, particularly on that fundamental problem of the relationship of mind and matter. Just as he conceived that the goal of education was to enable one to act, his conclusions in philosophy were the kind with which one could live. Huxley settled on a practical philosophy—an empirical idealism that recognized that all we can know of the world are affectations of the mind. He thought that such a view must be the philosophy of scientific men. He also held a practical materialism in the sense that it involved placing physical phenomena in a chain of direct causation. Huxley summarized these views in his 1868 lecture on protoplasm, “On the Physical Basis of Life” (Collected Essays, I, 130–165). In his discussions of education and scientific method Huxley put a strong emphasis on clear and distinct ideas, very much in the Cartesian tradition. Also, Huxley emphasized what he called a duty of doubt, an active skepticism, from which he believed freedom of thought would necessarily follow. For Huxley this freedom of thought was an essential element in the scientific process. In this context Huxley coined the term “agnosticism”—which to him embodied no belief nor implied any—when he became a member of the Metaphysical Society. For Huxley agnosticism was an attitude, a tool of the intellect, and “the fundamental axiom of modern science.” It involved, positively, following one’s intellect as far as it would go and, negatively, not accepting any conclusions which were not clearly demonstrable.

Huxley regarded the Bible highly, both as one of the great works of English literature and as a defense of freedom and liberty. For him it was “the Magna Charta of the poor and oppressed” insofar as it supported the concept of righteousness. To a great extent the Protestants had shifted the notion of infallibility from the Church to the Book, the Bible. It was in this context that Huxley first became involved in Biblical controversy, on the subject of the authority of Genesis. Huxley applied agnosticism, as a method, to this and other Biblical problems, including the divine inspiration of the New Testament Gospels and various revelations and miracles. Huxley often argued that matters of morality were independent of religion and theology, for example, in his letter to Charles Kingsley after the death of Huxley’s first son, Noel.

Huxley was also a man of affairs. Between 1862 and 1884 he served on ten royal commissions investigating problems of education, fisheries, and vivisection. He held office in diverse scientific societies, particularly the Ethnological, Geological, and Royal societies, and the British Association, each of which he served as president. His role on the London School Board has been mentioned. Huxley was a member of the X-Club, which served to keep a small group of scientific friends in contact, and of that unique group the Metaphysical Society, before which he spoke on such topics as “Has a Frog a Soul?” His scientific and public works led to many honors, including the Royal, Copley, and Darwin medals from the Royal Society and ultimately appointment as a Privy Councillor. In all of his multifarious activities as scientist, educator, and public figure Huxley’s success was dependent more than anything else on his clear thinking, his scrupulous weighing of all pertinent evidence, and, once he had reached a decision, on his effort to lead those around him, step by step, to see the rightness of his position.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. Original Works. The majority of Huxley’s shorter writings are available in two collections. The Scientific Memoirs of Thomas Henry Huxley, Michael Foster and E. Ray Lankester, eds. 4 vols. and supp. (London, 1898-1903), contains probably all of Huxley’s important scientific papers as well as reports of his Royal Institution Friday Evening Discourses. Huxley selected and arranged his Collected Essays (London, 1893-1894), writing a preface to each of the nine volumes; the planned tenth volume was never completed. Huxley’s Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake (London, 1935), Julian Huxley, ed., was long lost among the family’s old account books. During the period he needed to write for money, Huxley, with George Busk, translated and edited Kölliker’s Manual of Human Histology (London, 1853); with Arthur Henfrey he edited two volumes of Taylor’s Scientific Memoirs (London, 1853-1854). The most important of Huxley’s separate scientific writings was his Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (London, 1863).

As introductory textbooks of zoology Huxley wrote An Introduction to the Classification of Animals (London, 1869) and The Crayfish: an Introduction to the Study of Zoology (London, 1879). His A Manual of the Anatomy of Vertebrated Anmials (London, 1871) and A Manual of the Anatomy of Invertebrated Animals (London, 1877) were comprehensive treatments which served as standard textbooks.

The great bulk of Huxley’s manuscripts are in the Imperial College of Science and Technology, London. These have been ably catalogued in Warren R. Dawson, The Huxley Papers. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Correspondence, Manuscripts and Miscellaneous Papers...(London, 1946). See also J. Pingree, Thomas Henry Huxley: List of His Correspondence With Miss Henrietta Anne Heathorn, Later Mrs. Huxley, 1847-1854 (London, 1969) and Thomas Henry Huxley: A List of His Scientific Notebooks, Drawings and Other Papers (London, 1968).

Huxley was a prolific correspondent, and his letters may be found in many collections of papers of his correspondents.

II. Secondary Literature. The standard source for Huxley’s life is Leonard Huxley, Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley, 2 vols. (London, 1900), which includes extensive bibliographies of his addresses, books, and scientific papers, as well as lists of honors he received and scientific societies and Royal Commissions of which he was a member. This work is weak on the period of the voyage of the Rattlesnake, apparently because the Diary of the voyage had not then been found.

Probably the best analysis of Huxley’s scientific work is P. Chalmers Mitchell, Thomas Henry Huxley. A Sketch of His Life and Work (London, 1900); see also Michael Foster, “Obituary of T. H. Huxley,” in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 59 (1896), 46-66. Most of the many biographical writings on Huxley rely heavily on the above three items. The various works devoted to the lives and letters of Charles Darwin, Joseph Hooker, and Charles Lyell are valuable for additional information and other views of events in Huxley’s life.

Cyril Bibby, T. H. Huxley: Scientist, Humanist and Educator (London, 1959), is based on extensive original research and emphasizes Huxley’s activities and writings as an educator and a public figure, topics which because of space are only touched on in the above article.

For the debate following Huxley’s “On the Physical Basis of Life,” see Gerald L. Geison, “The Protoplasmic Theory of Life and the Vitalist-Mechanist Debate,” in Isis, 60 (1969), 273-292. Finally, Aldous Huxley discussed his grandfather’s success as a writer in his 1932 Huxley Memorial Lecture, “T. H. Hucley as a Literary Man”; reprinted in Aldous Huxley, The Olive Tree (London, 1937).