About Aristotle

March 15, 2017

About Plotinus

March 16, 2017The Greek Foundation

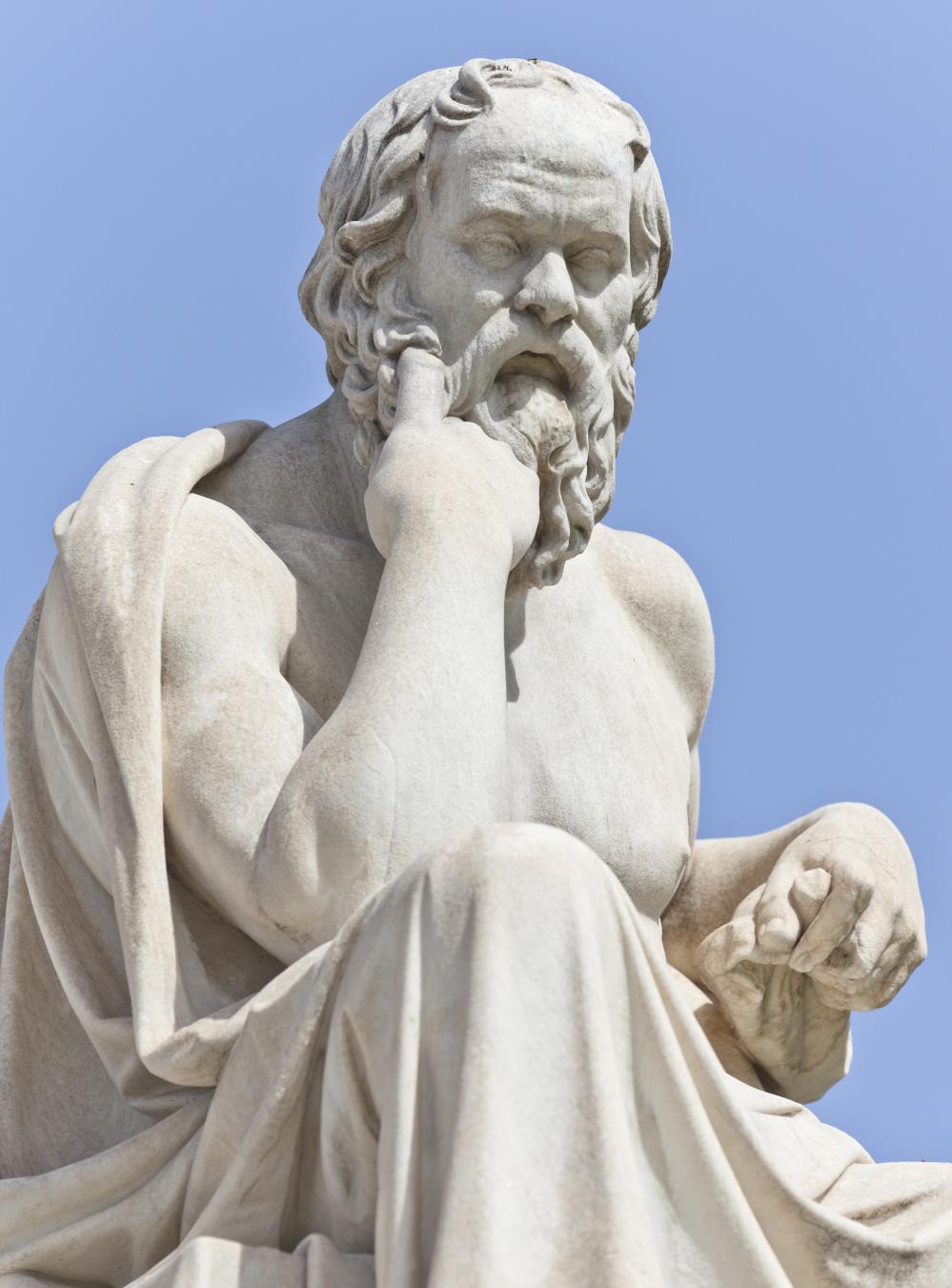

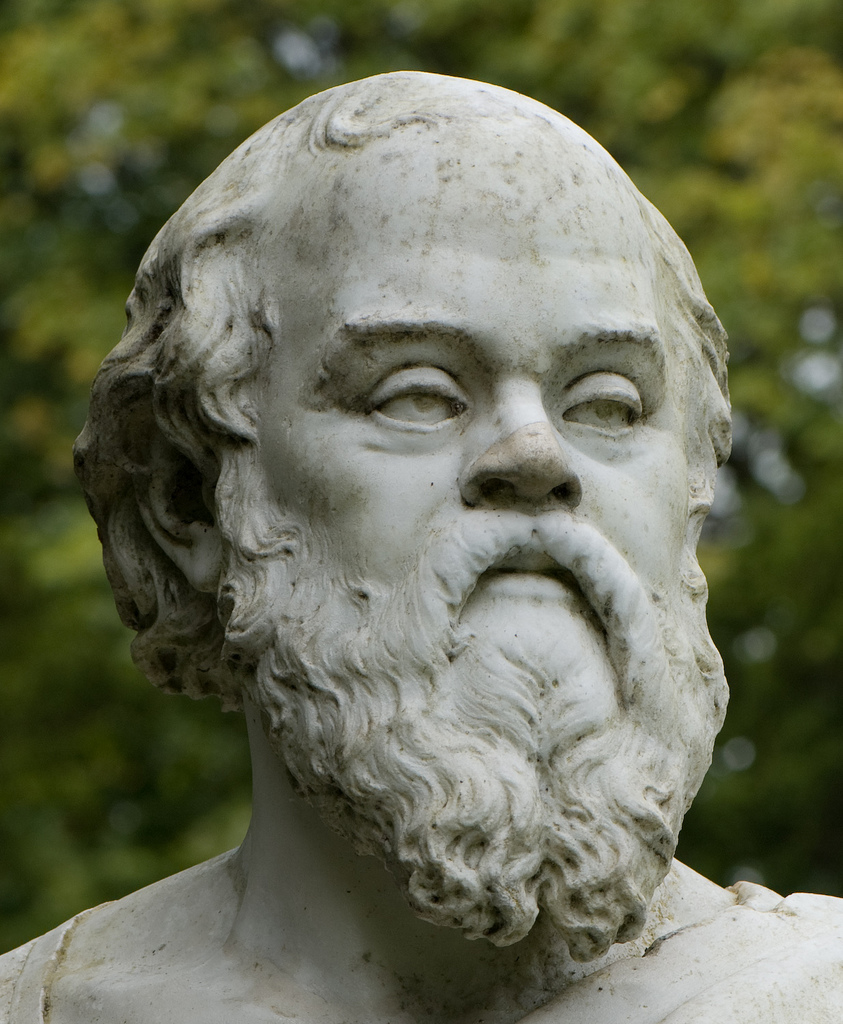

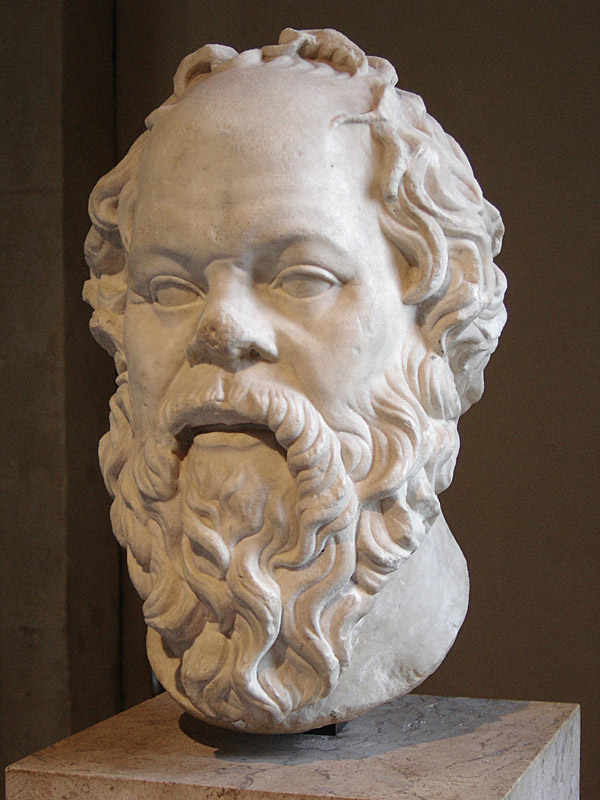

About Socrates

S ocrates is one of the few individuals whom one could say has so-shaped the cultural and intellectual development of the world that, without him, history would be profoundly different. He is best known for his association with the Socratic method of question and answer, his claim that he was ignorant (or aware of his own absence of knowledge), and his claim that the unexamined life is not worth living, for human beings. He was the inspiration for Plato, the thinker widely held to be the founder of the Western philosophical tradition. Plato in turn served as the teacher of Aristotle, thus establishing the famous triad of ancient philosophers: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Unlike other philosophers of his time and ours, Socrates never wrote anything down but was committed to living simply and to interrogating the everyday views and popular opinions of those in his home city of Athens. At the age of 70, he was put to death at the hands of his fellow citizens on charges of impiety and corruption of the youth. His trial, along with the social and political context in which occurred, has warranted as much treatment from historians and classicists as his arguments and methods have from philosophers.

This article gives an overview of Socrates: who he was, what he thought, and his purported method. It is both historical and philosophical. At the same time, it contains reflections on the difficult nature of knowing anything about a person who never committed any of his ideas to the written word. Much of what is known about Socrates comes to us from Plato, although Socrates appears in the works of other ancient writers as well as those who follow Plato in the history of philosophy. This article recognizes that finding the original Socrates may be impossible, but it attempts to achieve a close approximation.

1. Biography: Who was Socrates?

a. The Historical Socrates

i. Birth and Early Life

Socrates was born in Athens in the year 469 B.C.E. to Sophroniscus, a stonemason, and Phaenarete, a midwife. His family was not extremely poor, but they were by no means wealthy, and Socrates could not claim that he was of noble birth like Plato. He grew up in the political deme or district of Alopece, and when he turned 18, began to perform the typical political duties required of Athenian males. These included compulsory military service and membership in the Assembly, the governing body responsible for determining military strategy and legislation.

In a culture that worshipped male beauty, Socrates had the misfortune of being born incredibly ugly. Many of our ancient sources attest to his rather awkward physical appearance, and Plato more than once makes reference to it (Theaetetus 143e, Symposium, 215a-c; also Xenophon Symposium 4.19, 5.5-7 and Aristophanes Clouds 362). Socrates was exophthalmic, meaning that his eyes bulged out of his head and were not straight but focused sideways. He had a snub nose, which made him resemble a pig, and many sources depict him with a potbelly. Socrates did little to help his odd appearance, frequently wearing the same cloak and sandals throughout both the day and the evening. Plato’s Symposium (174a) offers us one of the few accounts of his caring for his appearance.

As a young man Socrates was given an education appropriate for a person of his station. By the middle of the 5th century B.C.E., all Athenian males were taught to read and write. Sophroniscus, however, also took pains to give his son an advanced cultural education in poetry, music, and athletics. In both Plato and Xenophon, we find a Socrates that is well versed in poetry, talented at music, and quite at-home in the gymnasium. In accordance with Athenian custom, his father also taught him a trade, though Socrates did not labor at it on a daily basis. Rather, he spent his days in the agora (the Athenian marketplace), asking questions of those who would speak with him. While he was poor, he quickly acquired a following of rich young aristocrats—one of whom was Plato—who particularly enjoyed hearing him interrogate those that were purported to be the wisest and most influential men in the city.

Socrates was married to Xanthippe, and according to some sources, had a second wife. Most suggest that he first married Xanthippe, and that she gave birth to his first son, Lamprocles. He is alleged to have married his second wife, Myrto, without dowry, and she gave birth to his other two sons, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. Various accounts attribute Sophroniscus to Xanthippe, while others even suggest that Socrates was married to both women simultaneously because of a shortage of males in Athens at the time. In accordance with Athenian custom, Socrates was open about his physical attraction to young men, though he always subordinated his physical desire for them to his desire that they improve the condition of their souls.

Socrates fought valiantly during his time in the Athenian military. Just before the Peloponnesian War with Sparta began in 431 B.C.E, he helped the Athenians win the battle of Potidaea (432 B.C.E.), after which he saved the life of Alcibiades, the famous Athenian general. He also fought as one of 7,000 hoplites aside 20,000 troops at the battle of Delium (424 B.C.E.) and once more at the battle of Amphipolis (422 B.C.E.). Both battles were defeats for Athens.

Despite his continued service to his city, many members of Athenian society perceived Socrates to be a threat to their democracy, and it is this suspicion that largely contributed to his conviction in court. It is therefore imperative to understand the historical context in which his trial was set.

ii. Later Life and Trial

1. The Peloponnesian War and the Threat to Democracy

Between 431—404 B.C.E. Athens fought one of its bloodiest and most protracted conflicts with neighboring Sparta, the war that we now know as the Peloponnesian War. Aside from the fact that Socrates fought in the conflict, it is important for an account of his life and trial because many of those with whom Socrates spent his time became either sympathetic to the Spartan cause at the very least or traitors to Athens at worst. This is particularly the case with those from the more aristocratic Athenian families, who tended to favor the rigid and restricted hierarchy of power in Sparta instead of the more widespread democratic distribution of power and free speech to all citizens that obtained in Athens. Plato more than once places in the mouth of his character Socrates praise for Sparta (Protagoras 342b, Crito 53a; cf. Republic 544c in which most people think the Spartan constitution is the best). The political regime of the Republic is marked by a small group of ruling elites that preside over the citizens of the ideal city.

There are a number of important historical moments throughout the war leading up to Socrates’ trial that figure in the perception of him as a traitor. Seven years after the battle of Amphipolis, the Athenian navy was set to invade the island of Sicily, when a number of statues in the city called “herms”, dedicated to the god Hermes, protector of travelers, were destroyed. Dubbed the ‘Mutilation of the Herms’ (415 B.C.E.), this event engendered not only a fear of those who might seek to undermine the democracy, but those who did not respect the gods. In conjunction with these crimes, Athens witnessed the profanation of the Eleusinian mysteries, religious rituals that were to be conducted only in the presence of priests but that were in this case performed in private homes without official sanction or recognition of any kind. Amongst those accused and persecuted on suspicion of involvement in the crimes were a number of Socrates’ associates, including Alcibiades, who was recalled from his position leading the expedition in Sicily. Rather than face prosecution for the crime, Alcibiades escaped and sought asylum in Sparta.

Though Alcibiades was not the only of Socrates’ associates implicated in the sacrilegious crimes (Charmides and Critias were suspected as well), he is arguably the most important. Socrates had by many counts been in love with Alcibiades and Plato depicts him pursuing or speaking of his love for him in many dialogues (Symposium 213c-d, Protagoras 309a, Gorgias 481d, Alcibiades I 103a-104c, 131e-132a). Alcibiades is typically portrayed as a wandering soul (Alcibiades I 117c-d), not committed to any one consistent way of life or definition of justice. Instead, he was a kind of cameleon-like flatterer that could change and mold himself in order to please crowds and win political favor (Gorgias 482a). In 411 B.C.E., a group of citizens opposed to the Athenian democracy led a coup against the government in hopes of establishing an oligarchy. Though the democrats put down the coup later that year and recalled Alcibiades to lead the Athenian fleet in the Hellespont, he aided the oligarchs by securing for them an alliance with the Persian satraps. Alcibiades therefore did not just aid the Spartan cause but allied himself with Persian interests as well. His association with the two principal enemies of Athens reflected poorly on Socrates, and Xenophon tells us that Socrates’ repeated association with and love for Alcibiades was instrumental in the suspicion that he was a Spartan apologist.

Sparta finally defeated Athens in 404 B.C.E., just five years before Socrates’ trial and execution. Instead of a democracy, they installed as rulers a small group of Athenians who were loyal to Spartan interests. Known as “The Thirty” or sometimes as the “Thirty Tyrants”, they were led by Critias, a known associate of Socrates and a member of his circle. Critias’ nephew Charmides, about whom we have a Platonic dialogue of the same name, was also a member. Though Critias put forth a law prohibiting Socrates from conducting discussions with young men under the age of 30, Socrates’ earlier association with him—as well as his willingness to remain in Athens and endure the rule of the Thirty rather than flee—further contributed to the growing suspicion that Socrates was opposed to the democratic ideals of his city.

The Thirty ruled tyrannically—executing a number of wealthy Athenians as well as confiscating their property, arbitrarily arresting those with democratic sympathies, and exiling many others—until they were overthrown in 403 B.C.E. by a group of democratic exiles returning to the city. Both Critias and Charmides were killed and, after a Spartan-sponsored peace accord, the democracy was restored. The democrats proclaimed a general amnesty in the city and thereby prevented politically motivated legal prosecutions aimed at redressing the terrible losses incurred during the reign of the Thirty. Their hope was to maintain unity during the reestablishment of their democracy.

One of Socrates’ main accusers, Anytus, was one of the democratic exiles that returned to the city to assist in the overthrow of the Thirty. Plato’s Meno, set in the year 402 B.C.E., imagines a conversation between Socrates and Anytus in which the latter argues that any citizen of Athens can teach virtue, an especially democratic view insofar as it assumes knowledge of how to live well is not the restricted domain of the esoteric elite or privileged few. In the discussion, Socrates argues that if one wants to know about virtue, one should consult an expert on virtue (Meno 91b-94e). The political turmoil of the city, rebuilding itself as a democracy after nearly thirty years of destruction and bloodshed, constituted a context in which many citizens were especially fearful of threats to their democracy that came not from the outside, but from within their own city.

While many of his fellow citizens found considerable evidence against Socrates, there was also historical evidence in addition to his military service for the case that he was not just a passive but an active supporter of the democracy. For one thing, just as he had associates that were known oligarchs, he also had associates that were supporters of the democracy, including the metic family of Cephalus and Socrates’ friend Chaerephon, the man who reported that the oracle at Delphi had proclaimed that no man was wiser than Socrates. Additionally, when he was ordered by the Thirty to help retrieve the democratic general Leon from the island of Salamis for execution, he refused to do so. His refusal could be understood not as the defiance of a legitimately established government but rather his allegiance to the ideals of due process that were in effect under the previously instituted democracy. Indeed, in Plato’s Crito, Socrates refuses to escape from prison on the grounds that he lived his whole life with an implied agreement with the laws of the democracy (Crito 50a-54d). Notwithstanding these facts, there was profound suspicion that Socrates was a threat to the democracy in the years after the end of the Peloponnesian War. But because of the amnesty, Anytus and his fellow accusers Meletus and Lycon were prevented from bringing suit against Socrates on political grounds. They opted instead for religious grounds.

2. Greek Religion and Socrates’ Impiety

Because of the amnesty the charges made against Socrates were framed in religious terms. As recounted by Diogenes Laertius (1.5.40), the charges were stated as follows: “Socrates does criminal wrong by not recognizing the gods that the city recognizes, and furthermore by introducing new divinities; and he also does criminal wrong by corrupting the youth” (other accounts: Xenophon Memorabilia I.I.1 and Apology 11-12, Plato, Apology 24b and Euthyphro 2c-3b). Many people understood the charge about corrupting the youth to signify that Socrates taught his subversive views to others, a claim that he adamantly denies in his defense speech by claiming that he has no wisdom to teach (Plato, Apology 20c) and that he cannot be held responsible for the actions of those that heard him speak (Plato, Apology 33a-c).

It is now customary to refer to the principal written accusation on the deposition submitted to the Athenian court as an accusation of impiety, or unholiness. Rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices that were officially sanctioned by the city and its officials marked ancient Greek religion. The sacred was woven into the everyday experience of citizens who demonstrated their piety by correctly observing their ancestral traditions. Interpretation of the gods at their temples was the exclusive domain of priests appointed and recognized by the city. The boundary and separation between the religious and the secular that we find in many countries today therefore did not obtain in Athens. A religious crime was consequently an offense not just against the gods, but also against the city itself.

Socrates and his contemporaries lived in a polytheistic society, a society in which the gods did not create the world but were themselves created. Socrates would have been brought up with the stories of the gods recounted in Hesiod and Homer, in which the gods were not omniscient, omnibenevolent, or eternal, but rather power-hungry super-creatures that regularly intervened in the affairs of human beings. One thinks for example of Aphrodite saving Paris from death at the hands of Menelaus (Homer, Iliad 3.369-382) or Zeus sending Apollo to rescue the corpse of Sarpedon after his death in battle (Homer, Iliad 16.667-684). Human beings were to fear the gods, sacrifice to them, and honor them with festivals and prayers.

Socrates instead seemed to have a conception of the divine as always benevolent, truthful, authoritative, and wise. For him, divinity always operated in accordance with the standards of rationality. This conception of divinity, however, dispenses with the traditional conception of prayer and sacrifice as motivated by hopes for material payoff. Socrates’ theory of the divine seemed to make the most important rituals and sacrifices in the city entirely useless, for if the gods are all good, they will benefit human beings regardless of whether or not human beings make offerings to them. Jurors at his trial might have thought that, without the expectation of material reward or protection from the gods, Socrates was disconnecting religion from its practical roots and its connection with the civic identity of the city.

While Socrates was critical of blind acceptance of the gods and the myths we find in Hesiod and Homer, this in itself was not unheard of in Athens at the time. Solon, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Euripides had all spoken against the capriciousness and excesses of the gods without incurring penalty. It is possible to make the case that Socrates’ jurors might not have indicted him solely on questioning the gods or even of interrogating the true meaning of piety. Indeed, there was no legal definition of piety in Athens at the time, and jurors were therefore in a similar situation to the one in which we find Socrates in Plato’s Euthyphro, that is, in need of an inquiry into what the nature of piety truly is. What seems to have concerned the jurors was not only Socrates’ challenge to the traditional interpretation of the gods of the city, but his seeming allegiance to an entirely novel divine being, unfamiliar to anyone in the city.

This new divine being is what is known as Socrates’ daimon. Though it has become customary to think of a daimon as a spirit or quasi-divinity (for example, Symposium 202e-203a), in ancient Greek religion it was not solely a specific class of divine being but rather a mode of activity, a force that drives a person when no particular divine agent can be named (Burkett, 180). Socrates claimed to have heard a sign or voice from his days as a child that accompanied him and forbid him to pursue certain courses of action (Plato, Apology 31c-d, 40a-b, Euthydemus 272e-273a, Euthyphro 3b, Phaedrus 242b, Theages 128-131a, Theaetetus 150c-151b, Rep 496c; Xenophon, Apology 12, Memorabilia 1.1.3-5). Xenophon adds that the sign also issued positive commands (Memorablia 1.1.4, 4.3.12, 4.8.1, Apology 12). This sign was accessible only to Socrates, private and internal to his own mind. Whether Socrates received moral knowledge of any sort from the sign is a matter of scholarly debate, but beyond doubt is the strangeness of Socrates’ insistence that he took private instructions from a deity that was unlicensed by the city. For all the jurors knew, the deity could have been hostile to Athenian interests. Socrates’ daimon was therefore extremely influential in his indictment on the charge of worshipping new gods unknown to the city (Plato, Euthyphro 3b, Xenophon, Memorabilia I.1.2).

Whereas in Plato’s Apology Socrates makes no attempt to reconcile his divine sign with traditional views of piety, Xenophon’s Socrates argues that just as there are those who rely on birdcalls and receive guidance from voices, so he too is influenced by his daimon. However, Socrates had no officially sanctioned religious role in the city. As such, his attempt to assimilate himself to a seer or necromancer appointed by the city to interpret divine signs actually may have undermined his innocence, rather than help to establish it. His insistence that he had direct, personal access to the divine made him appear guilty to enough jurors that he was sentenced to death.

b. The Socratic Problem: the Philosophical Socrates

The Socratic problem is the problem faced by historians of philosophy when attempting to reconstruct the ideas of the original Socrates as distinct from his literary representations. While we know many of the historical details of Socrates’ life and the circumstances surrounding his trial, Socrates’ identity as a philosopher is much more difficult to establish. Because he wrote nothing, what we know of his ideas and methods comes to us mainly from his contemporaries and disciples.

There were a number of Socrates’ followers who wrote conversations in which he appears. These works are what are known as the logoi sokratikoi, or Socratic accounts. Aside from Plato and Xenophon, most of these dialogues have not survived. What we know of them comes to us from other sources. For example, very little survives from the dialogues of Antisthenes, whom Xenophon reports as one of Socrates’ leading disciples. Indeed, from polemics written by the rhetor Isocrates, some scholars have concluded that he was the most prominent Socratic in Athens for the first decade following Socrates’ death. Diogenes Laertius (6.10-13) attributes to Antisthenes a number of views that we recognize as Socratic, including that virtue is sufficient for happiness, the wise man is self-sufficient, only the virtuous are noble, the virtuous are friends, and good things are morally fine and bad things are base.

Aeschines of Sphettus wrote seven dialogues, all of which have been lost. It is possible for us to reconstruct the plots of two of them: the Alcibiades—in which Socrates shames Alcibiades into admitting he needs Socrates’ help to be virtuous—and the Aspasia—in which Socrates recommends the famous wife of Pericles as a teacher for the son of Callias. Aeschines’ dialogues focus on Socrates’ ability to help his interlocutor acquire self-knowledge and better himself.

Phaedo of Elis wrote two dialogues. His central use of Socrates is to show that philosophy can improve anyone regardless of his social class or natural talents. Euclides of Megara wrote six dialogues, about which we know only their titles. Diogenes Laertius reports that he held that the good is one, that insight and prudence are different names for the good, and that what is opposed to the good does not exist. All three are Socratic themes. Lastly, Aristippus of Cyrene wrote no Socratic dialogues but is alleged to have written a work entitled To Socrates.

The two Socratics on whom most of our philosophical understanding of Socrates depends are Plato and Xenophon. Scholars also rely on the works of the comic playwright Aristophanes and Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle.

i. Origin of the Socratic Problem

The Socratic problem first became pronounced in the early 19th century with the influential work of Friedrich Schleiermacher. Until this point, scholars had largely turned to Xenophon to identify what the historical Socrates thought. Schleiermacher argued that Xenophon was not a philosopher but rather a simple citizen-soldier, and that his Socrates was so dull and philosophically uninteresting that, reading Xenophon alone, it would be difficult to understand the reputation accorded Socrates by so many of his contemporaries and nearly all the schools of philosophy that followed him. The better portrait of Socrates, Schleiermacher claimed, comes to us from Plato.

Though many scholars have since jettisoned Xenophon as a legitimate source for representing the philosophical views of the historical Socrates, they remain divided over the reliability of the other three sources. For one thing, Aristophanes was a comic playwright, and therefore took considerable poetic license when scripting his characters. Aristotle, born 15 years after Socrates’ death, hears about Socrates primarily from Plato. Plato himself wrote dialogues or philosophical dramas, and thus cannot be understood to be presenting his readers with exact replicas or transcriptions of conversations that Socrates actually had. Furthermore, many scholars think that Plato’s so-called middle and late dialogues do not present the views of the historical Socrates.

We therefore see the difficult nature of the Socratic problem: because we don’t seem to have any consistently reliable sources, finding the true Socrates or the original Socrates proves to be an impossible task. What we are left with, instead, is a composite picture assembled from various literary and philosophical components that give us what we might think of as Socratic themes or motifs.

ii. Aristophanes

Born in 450 B.C.E., Aristophanes wrote a number of comic plays intended to satirize and caricature many of his fellow Athenians. His Clouds (423 B.C.E.) was so instrumental in parodying Socrates and painting him as a dangerous intellectual capable of corrupting the entire city that Socrates felt compelled in his trial defense to allude to the bad reputation he acquired as a result of the play (Plato, Apology 18a-b, 19c). Aristophanes was much closer in age to Socrates than Plato and Xenophon, and as such is the only one of our sources exposed to Socrates in his younger years.

In the play, Socrates is the head of a phrontistêrion, a school of learning where students are taught the nature of the heavens and how to win court cases. Socrates appears in a swing high above the stage, purportedly to better study the heavens. His patron deities, the clouds, represent his interest in meteorology and may also symbolize the lofty nature of reasoning that may take either side of an argument. The main plot of the play centers on an indebted man called Strepsiades, whose son Phidippides ends up in the school to learn how to help his father avoid paying off his debts. By the end of the play, Phidippides has beaten his father, arguing that it is perfectly reasonable to do so on the grounds that, just as it is acceptable for a father to spank his son for his own good, so it is acceptable for a son to hit a father for his own good. In addition to the theme that Socrates corrupts the youth, we therefore also find in the Clouds the origin of the rumor that Socrates makes the stronger argument the weaker and the weaker argument the stronger. Indeed, the play features a personification of the Stronger Argument—which represents traditional education and values—attacked by the Weaker Argument—which advocates a life of pleasure.

While the Clouds is Aristophanes’ most famous and comprehensive attack on Socrates, Socrates appears in other of his comedies as well. In the Birds (414 B.C.E.), Aristophanes coins a Greek verb based on Socrates’ name to insinuate that Socrates was truly a Spartan sympathizer (1280-83). Young men who were found “Socratizing” were expressing their admiration of Sparta and its customs. And in the Frogs (405), the Chorus claims that it is not refined to keep company with Socrates, who ignores the poets and wastes time with ‘frivolous words’ and ‘pompous word-scraping’ (1491-1499).

Aristophanes’ Socrates is a kind of variegated caricature of trends and new ideas emerging in Athens that he believed were threatening to the city. We find a number of such themes prevalent in Presocratic philosophy and the teachings of the Sophists, including those about natural science, mathematics, social science, ethics, political philosophy, and the art of words. Amongst other things, Aristophanes was troubled by the displacement of the divine through scientific explanations of the world and the undermining of traditional morality and custom by explanations of cultural life that appealed to nature instead of the gods. Additionally, he was reticent about teaching skill in disputation, for fear that a clever speaker could just as easily argue for the truth as argue against it. These issues constitute what is sometimes called the “new learning” developing in 5th century B.C.E. Athens, for which the Aristophanic Socrates is the iconic symbol.

iii. Xenophon

Born in the same decade as Plato (425 B.C.E.), Xenophon lived in the political deme of Erchia. Though he knew Socrates he would not have had as much contact with him as Plato did. He was not present in the courtroom on the day of Socrates’ trial, but rather heard an account of it later on from Hermogenes, a member of Socrates’ circle. His depiction of Socrates is found principally in four works: Apology—in which Socrates gives a defense of his life before his jurors—Memorabilia—in which Xenophon himself explicates the charges against Socrates and tries to defend him—Symposium—a conversation between Socrates and his friends at a drinking party—and Oeconomicus—a Socratic discourse on estate management. Socrates also appears in Xenophon’s Hellenica and Anabasis.

Xenophon’s reputation as a source on the life and ideas of Socrates is one on which scholars do not always agree. Largely thought to be a significant source of information about Socrates before the 19th century, for most of the 20th century Xenophon’s ability to depict Socrates as a philosopher was largely called into question. Following Schleiermacher, many argued that Xenophon himself was either a bad philosopher who did not understand Socrates, or not a philosopher at all, more concerned with practical, everyday matters like economics. However, recent scholarship has sought to challenge this interpretation, arguing that it assumes an understanding of philosophy as an exclusively speculative and critical endeavor that does not attend to the ancient conception of philosophy as a comprehensive way of life.

While Plato will likely always remain the principal source on Socrates and Socratic themes, Xenophon’s Socrates is distinct in philosophically interesting ways. He emphasizes the values of self-mastery (enkrateia), endurance of physical pain (karteria), and self-sufficiency (autarkeia). For Xenophon’s Socrates, self-mastery or moderation is the foundation of virtue (Memorabilia, 1.5.4). Whereas in Plato’s Apology the oracle tells Chaerephon that no one is wiser than Socrates, in Xenophon’s Apology Socrates claims that the oracle told Chaerephon that “no man was more free than I, more just, and more moderate” (Xenophon, Apology, 14).

Part of Socrates’ freedom consists in his freedom from want, precisely because he has mastered himself. As opposed to Plato’s Socrates, Xenophon’s Socrates is not poor, not because he has much, but because he needs little. Oeconomicus 11.3 for instance shows Socrates displeased with those who think him poor. One can be rich even with very little on the condition that one has limited his needs, for wealth is just the excess of what one has over what one requires. Socrates is rich because what he has is sufficient for what he needs (Memorabilia 1.2.1, 1.3.5, 4.2.38-9).

We also find Xenophon attributing to Socrates a proof of the existence of God. The argument holds that human beings are the product of an intelligent design, and we therefore should conclude that there is a God who is the maker (dēmiourgos) or designer of all things (Memorabilia 1.4.2-7). God creates a systematically ordered universe and governs it in the way our minds govern our bodies (Memorabilia 1.4.1-19, 4.3.1-18). While Plato’s Timaeus tells the story of a dēmiourgos creating the world, it is Timaeus, not Socrates, who tells the story. Indeed, Socrates speaks only sparingly at the beginning of the dialogue, and most scholars do not count as Socratic the cosmological arguments therein.

iv. Plato

Plato was Socrates’ most famous disciple, and the majority of what most people know about Socrates is known about Plato’s Socrates. Plato was born to one of the wealthiest and politically influential families in Athens in 427 B.C.E., the son of Ariston and Perictione. His brothers were Glaucon and Adeimantus, who are Socrates’ principal interlocutors for the majority of the Republic. Though Socrates is not present in every Platonic dialogue, he is in the majority of them, often acting as the main interlocutor who drives the conversation.

The attempt to extract Socratic views from Plato’s texts is itself a notoriously difficult problem, bound up with questions about the order in which Plato composed his dialogues, one’s methodological approach to reading them, and whether or not Socrates, or anyone else for that matter, speaks for Plato. Readers interested in the details of this debate should consult “Plato.” Generally speaking, the predominant view of Plato’s Socrates in the English-speaking world from the middle to the end of the 20th century was simply that he was Plato’s mouthpiece. In other words, anything Socrates says in the dialogues is what Plato thought at the time he wrote the dialogue. This view, put forth by the famous Plato scholar Gregory Vlastos, has been challenged in recent years, with some scholars arguing that Plato has no mouthpiece in the dialogues (see Cooper xxi-xxiii). While we can attribute to Plato certain doctrines that are consistent throughout his corpus, there is no reason to think that Socrates, or any other speaker, always and consistently espouses these doctrines.

The main interpretive obstacle for those seeking the views of Socrates from Plato is the question of the order of the dialogues. Thrasyllus, the 1st century (C.E.) Platonist who was the first to arrange the dialogues according to a specific paradigm, organized the dialogues into nine tetralogies, or groups of four, on the basis of the order in which he believed they should be read. Another approach, customary for most scholars by the late 20th century, groups the dialogues into three categories on the basis of the order in which Plato composed them. Plato begins his career, so the narrative goes, representing his teacher Socrates in typically short conversations about ethics, virtue, and the best human life. These are “early” dialogues. Only subsequently does Plato develop his own philosophical views—the most famous of which is the doctrine of the Forms or Ideas—that Socrates defends. These “middle” dialogues put forth positive doctrines that are generally thought to be Platonic and not Socratic. Finally, towards the end of his life, Plato composes dialogues in which Socrates typically either hardly features at all or is altogether absent. These are the “late” dialogues.

There are a number of complications with this interpretive thesis, and many of them focus on the portrayal of Socrates. Though the Gorgias is an early dialogue, Socrates concludes the dialogue with a myth that some scholars attribute to a Pythagorean influence on Plato that he would not have had during Socrates’ lifetime. Though the Parmenides is a middle dialogue, the younger Socrates speaks only at the beginning before Parmenides alone speaks for the remainder of the dialogue. While the Philebus is a late dialogue, Socrates is the main speaker. Some scholars identify the Meno as an early dialogue because Socrates refutes Meno’s attempts to articulate the nature of virtue. Others, focusing on Socrates’ use of the theory of recollection and the method of hypothesis, argue that it is a middle dialogue. Finally, while Plato’s most famous work the Republic is a middle dialogue, some scholars make a distinction within the Republic itself. The first book, they argue, is Socratic, because in it we find Socrates refuting Thrasymachus’ definition of justice while maintaining that he knows nothing about justice. The rest of the dialogue they claim, with its emphasis on the division of the soul and the metaphysics of the Forms, is Platonic.

To discern a consistent Socrates in Plato is therefore a difficult task. Instead of speaking about chronology of composition, contemporary scholars searching for views that are likely to have been associated with the historical Socrates generally focus on a group of dialogues that are united by topical similarity. These “Socratic dialogues” feature Socrates as the principal speaker, challenging his interlocutor to elaborate on and critically examine his own views while typically not putting forth substantive claims of his own. These dialogues—including those that some scholars think are not written by Plato and those that most scholars agree are not written by Plato but that Thrasyllus included in his collection—are as follows: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Alcibiades I, Alcibiades II, Hipparchus, Rival Lovers, Theages, Charmides, Laches, Lysis, Euthydemus, Protagoras, Gorgias, Meno, Greater Hippias, Lesser Hippias, Ion, Menexenus, Clitophon, Minos. Some of the more famous positions Socrates defends in these dialogues are covered in the content section.

v. Aristotle

Aristotle was born in 384 B.C.E., 15 years after the death of Socrates. At the age of eighteen, he went to study at Plato’s Academy, and remained there for twenty years. Afterwards, he traveled throughout Asia and was invited by Phillip II of Macedon to tutor his son Alexander, known to history as Alexander the Great. While Aristotle would never have had the chance to meet Socrates, we have in his writings an account of both Socrates’ method and the topics about which he had conversations. Given the likelihood that Aristotle heard about Socrates from Plato and those at his Academy, it is not surprising that most of what he says about Socrates follows the depiction of him in the Platonic dialogues.

Aristotle related four concrete points about Socrates. The first is that Socrates asked questions without supplying an answer of his own, because he claimed to know nothing (De Elenchis Sophisticus 1836b6-8). The picture of Socrates here is consistent with that of Plato’s Apology. Second, Aristotle claims that Socrates never asked questions about nature, but concerned himself only with ethical questions. Aristotle thus attributes to the historical Socrates both the method and topics we find in Plato’s Socratic dialogues.

Third, Aristotle claims that Socrates is the first to have employed epagōgē, a word typically rendered in English as “induction.” This translation, however, is misleading, lest we impute to Socrates a preference for inductive reasoning as opposed to deductive reasoning. The term better indicates that Socrates was fond or arguing via the use of analogy. For instance, just as a doctor does not practice medicine for himself but for the best interest of his patient, so the ruler in the city takes no account of his own personal profit, but is rather interested in caring for his citizens (Republic 342d-e).

The fourth and final claim Aristotle makes about Socrates itself has two parts. First, Socrates was the first to ask the question, ti esti: what is it? For example, if someone were to suggest to Socrates that our children should grow up to be courageous, he would ask, what is courage? That is, what is the universal definition or nature that holds for all examples of courage? Second, as distinguished from Plato, Socrates did not separate universals from their particular instantiations. For Plato, the noetic object, the knowable thing, is the separate universal, not the particular. Socrates simply asked the “what is it” question (on this and the previous two points, see Metaphysics I.6.987a29-b14; cf. b22-24, b27-33, and see XIII.4.1078b12-34).

2. Content: What does Socrates Think?

Given the nature of these sources, the task of recounting what Socrates thought is not an easy one. Nonetheless, reading Plato’s Apology, it is possible to articulate a number of what scholars today typically associate with Socrates. Plato the author has his Socrates claim that Plato was present in the courtroom for Socrates’ defense (Apology 34a), and while this cannot mean that Plato records the defense as a word for word transcription, it is the closest thing we have to an account of what Socrates actually said at a concrete point in his life.

a. Presocratic Philosophy and the Sophists

Socrates opens his defense speech by defending himself against his older accusers (Apology 18a), claiming they have poisoned the minds of his jurors since they were all young men. Amongst these accusers was Aristophanes. In addition to the claim that Socrates makes the worse argument into the stronger, there is a rumor that Socrates idles the day away talking about things in the sky and below the earth. His reply is that he never discusses such topics (Apology 18a-c). Socrates is distinguishing himself here not just from the sophists and their alleged ability to invert the strength of arguments, but from those we have now come to call the Presocratic philosophers.

The Presocratics were not just those who came before Socrates, for there are some Presocratic philosophers who were his contemporaries. The term is sometimes used to suggest that, while Socrates cared about ethics, the Presocratic philosophers did not. This is misleading, for we have evidence that a number of Presocratics explored ethical issues. The term is best used to refer to the group of thinkers whom Socrates did not influence and whose fundamental uniting characteristic was that they sought to explain the world in terms of its own inherent principles. The 6th cn. Milesian Thales, for instance, believed that the fundamental principle of all things was water. Anaximander believed the principle was the indefinite (apeiron), and for Anaxamines it was air. Later in Plato’s Apology (26d-e), Socrates rhetorically asks whether Meletus thinks he is prosecuting Anaxagoras, the 5th cn. thinker who argued that the universe was originally a mixture of elements that have since been set in motion by Nous, or Mind. Socrates suggests that he does not engage in the same sort of cosmological inquiries that were the main focus of many Presocratics.

The other group against which Socrates compares himself is the Sophists, learned men who travelled from city to city offering to teach the youth for a fee. While he claims he thinks it an admirable thing to teach as Gorgias, Prodicus, or Hippias claim they can (Apology 20a), he argues that he himself does not have knowledge of human excellence or virtue (Apology 20b-c). Though Socrates inquires after the nature of virtue, he does not claim to know it, and certainly does not ask to be paid for his conversations.

b. Socratic Themes in Plato’s Apology

i. Socratic Ignorance

Plato’s Socrates moves next to explain the reason he has acquired the reputation he has and why so many citizens dislike him. The oracle at Delphi told Socrates’ friend Chaerephon, “no one is wiser than Socrates” (Apology 21a). Socrates explains that he was not aware of any wisdom he had, and so set out to find someone who had wisdom in order to demonstrate that the oracle was mistaken. He first went to the politicians but found them lacking wisdom. He next visited the poets and found that, though they spoke in beautiful verses, they did so through divine inspiration, not because they had wisdom of any kind. Finally, Socrates found that the craftsmen had knowledge of their own craft, but that they subsequently believed themselves to know much more than they actually did. Socrates concluded that he was better off than his fellow citizens because, while they thought they knew something and did not, he was aware of his own ignorance. The god who speaks through the oracle, he says, is truly wise, whereas human wisdom is worth little or nothing (Apology 23a).

This awareness of one’s own absence of knowledge is what is known as Socratic ignorance, and it is arguably the thing for which Socrates is most famous. Socratic ignorance is sometimes called simple ignorance, to be distinguished from the double ignorance of the citizens with whom Socrates spoke. Simple ignorance is being aware of one’s own ignorance, whereas double ignorance is not being aware of one’s ignorance while thinking that one knows. In showing many influential figures in Athens that they did not know what they thought they did, Socrates came to be despised in many circles.

It is worth nothing that Socrates does not claim here that he knows nothing. He claims that he is aware of his ignorance and that whatever it is that he does know is worthless. Socrates has a number of strong convictions about what makes for an ethical life, though he cannot articulate precisely why these convictions are true. He believes for instance that it is never just to harm anyone, whether friend or enemy, but he does not, at least in Book I of the Republic, offer a systematic account of the nature of justice that could demonstrate why this is true. Because of his insistence on repeated inquiry, Socrates has refined his convictions such that he can both hold particular views about justice while maintaining that he does not know the complete nature of justice.

We can see this contrast quite clearly in Socrates’ cross-examination of his accuser Meletus. Because he is charged with corrupting the youth, Socrates inquires after who it is that helps the youth (Apology, 24d-25a). In the same way that we take a horse to a horse trainer to improve it, Socrates wants to know the person to whom we take a young person to educate him and improve him. Meletus’ silence condemns him: he has never bothered to reflect on such matters, and therefore is unaware of his ignorance about matters that are the foundation of his own accusation (Apology 25b-c). Whether or not Socrates—or Plato for that matter—actually thinks it is possible to achieve expertise in virtue is a subject on which scholars disagree.

ii. Priority of the Care of the Soul

Throughout his defense speech (Apology 20a-b, 24c-25c, 31b, 32d, 36c, 39d) Socrates repeatedly stresses that a human being must care for his soul more than anything else (see also Crito 46c-47d, Euthyphro 13b-c, Gorgias 520a4ff). Socrates found that his fellow citizens cared more for wealth, reputation, and their bodies while neglecting their souls (Apology 29d-30b). He believed that his mission from the god was to examine his fellow citizens and persuade them that the most important good for a human being was the health of the soul. Wealth, he insisted, does not bring about human excellence or virtue, but virtue makes wealth and everything else good for human beings (Apology 30b).

Socrates believes that his mission of caring for souls extends to the entirety of the city of Athens. He argues that the god gave him to the city as a gift and that his mission is to help improve the city. He thus attempts to show that he is not guilty of impiety precisely because everything he does is in response to the oracle and at the service of the god. Socrates characterizes himself as a gadfly and the city as a sluggish horse in need of stirring up (Apology 30e). Without philosophical inquiry, the democracy becomes stagnant and complacent, in danger of harming itself and others. Just as the gadfly is an irritant to the horse but rouses it to action, so Socrates supposes that his purpose is to agitate those around him so that they begin to examine themselves. One might compare this claim with Socrates’ assertion in the Gorgias that, while his contemporaries aim at gratification, he practices the true political craft because he aims at what is best (521d-e). Such comments, in addition to the historical evidence that we have, are Socrates’ strongest defense that he is not only not a burden to the democracy but a great asset to it.

iii. The Unexamined Life

After the jury has convicted Socrates and sentenced him to death, he makes one of the most famous proclamations in the history of philosophy. He tells the jury that he could never keep silent, because “the unexamined life is not worth living for human beings” (Apology 38a). We find here Socrates’ insistence that we are all called to reflect upon what we believe, account for what we know and do not known, and generally speaking to seek out, live in accordance with, and defend those views that make for a well lived and meaningful life.

Some scholars call attention to Socrates’ emphasis on human nature here, and argue that the call to live examined lives follows from our nature as human beings. We are naturally directed by pleasure and pain. We are drawn to power, wealth and reputation, the sorts of values to which Athenians were drawn as well. Socrates’ call to live examined lives is not necessarily an insistence to reject all such motivations and inclinations but rather an injunction to appraise their true worth for the human soul. The purpose of the examined life is to reflect upon our everyday motivations and values and to subsequently inquire into what real worth, if any, they have. If they have no value or indeed are even harmful, it is upon us to pursue those things that are truly valuable.

One can see in reading the Apology that Socrates examines the lives of his jurors during his own trial. By asserting the primacy of the examined life after he has been convicted and sentenced to death, Socrates, the prosecuted, becomes the prosecutor, surreptitiously accusing those who convicted him of not living a life that respects their own humanity. He tells them that by killing him they will not escape examining their lives. To escape giving an account of one’s life is neither possible nor good, Socrates claims, but it is best to prepare oneself to be as good as possible (Apology 39d-e).

We find here a conception of a well-lived life that differs from one that would likely be supported by many contemporary philosophers. Today, most philosophers would argue that we must live ethical lives (though what this means is of course a matter of debate) but that it is not necessary for everyone to engage in the sort of discussions Socrates had everyday, nor must one do so in order to be considered a good person. A good person, we might say, lives a good life insofar as he does what is just, but he does not necessarily need to be consistently engaged in debates about the nature of justice or the purpose of the state. No doubt Socrates would disagree, not just because the law might be unjust or the state might do too much or too little, but because, insofar as we are human beings, self-examination is always beneficial to us.

c. Other Socratic Positions and Arguments

In addition to the themes one finds in the Apology, the following are a number of other positions in the Platonic corpus that are typically considered Socratic.

i. Unity of Virtue; All Virtue is Knowledge

In the Protagoras (329b-333b) Socrates argues for the view that all of the virtues—justice, wisdom, courage, piety, and so forth—are one. He provides a number of arguments for this thesis. For example, while it is typical to think that one can be wise without being temperate, Socrates rejects this possibility on the grounds that wisdom and temperance both have the same opposite: folly. Were they truly distinct, they would each have their own opposites. As it stands, the identity of their opposites indicates that one cannot possess wisdom without temperance and vice versa.

This thesis is sometimes paired with another Socratic, view, that is, that virtue is a form of knowledge (Meno 87e-89a; cf. Euthydemus 278d-282a). Things like beauty, strength, and health benefit human beings, but can also harm them if they are not accompanied by knowledge or wisdom. If virtue is to be beneficial it must be knowledge, since all the qualities of the soul are in themselves neither beneficial not harmful, but are only beneficial when accompanied by wisdom and harmful when accompanied by folly.

ii. No One Errs Knowingly/No One Errs Willingly

Socrates famously declares that no one errs or makes mistakes knowingly (Protagoras 352c, 358b-b). Here we find an example of Socrates’ intellectualism. When a person does what is wrong, their failure to do what is right is an intellectual error, or due to their own ignorance about what is right. If the person knew what was right, he would have done it. Hence, it is not possible for someone simultaneously know what is right and do what is wrong. If someone does what is wrong, they do so because they do not know what is right, and if they claim the have known what was right at the time when they committed the wrong, they are mistaken, for had they truly known what was right, they would have done it.

Socrates therefore denies the possibility of akrasia, or weakness of the will. No one errs willingly (Protagoras 345c4-e6). While it might seem that Socrates is equivocating between knowingly and willingly, a look at Gorgias 466a-468e helps clarify his thesis. Tyrants and orators, Socrates tells Polus, have the least power of any member of the city because they do not do what they want. What they do is not good or beneficial even though human beings only want what is good or beneficial. The tyrant’s will, corrupted by ignorance, is in such a state that what follows from it will necessarily harm him. Conversely, the will that is purified by knowledge is in such a state that what follows from it will necessarily be beneficial.

iii. All Desire is for the Good

One of the premises of the argument just mentioned is that human beings only desire the good. When a person does something for the sake of something else, it is always the thing for the sake of which he is acting that he wants. All bad things or intermediate things are done not for themselves but for the sake of something else that is good. When a tyrant puts someone to death, for instance, he does this because he thinks it is beneficial in some way. Hence his action is directed towards the good because this is what he truly wants (Gorgias 467c-468b).

A similar version of this argument is in the Meno, 77b-78b. Those that desire bad things do not know that they are truly bad; otherwise, they would not desire them. They do not naturally desire what is bad but rather desire those things that they believe to be good but that are in fact bad. They desire good things even though they lack knowledge of what is actually good.

iv. It is Better to Suffer an Injustice Than to Commit One

Socrates infuriates Polus with the argument that it is better to suffer an injustice than commit one (Gorgias 475a-d). Polus agrees that it is more shameful to commit an injustice, but maintains it is not worse. The worst thing, in his view, is to suffer injustice. Socrates argues that, if something is more shameful, it surpasses in either badness or pain or both. Since committing an injustice is not more painful than suffering one, committing an injustice cannot surpass in pain or both pain and badness. Committing an injustice surpasses suffering an injustice in badness; differently stated, committing an injustice is worse than suffering one. Therefore, given the choice between the two, we should choose to suffer rather than commit an injustice.

This argument must be understood in terms of the Socratic emphasis on the care of the soul. Committing an injustice corrupts one’s soul, and therefore committing injustice is the worst thing a person can do to himself (cf. Crito 47d-48a, Republic I 353d-354a). If one commits injustice, Socrates goes so far as to claim that it is better to seek punishment than avoid it on the grounds that the punishment will purge or purify the soul of its corruption (Gorgias 476d-478e).

v. Eudaimonism

The Greek word for happiness is eudaimonia, which signifies not merely feeling a certain way but being a certain way. A different way of translating eudaimonia is well-being. Many scholars believe that Socrates holds two related but not equivalent principles regarding eudaimonia: first, that it is rationally required that a person make his own happiness the foundational consideration for his actions, and second, that each person does in fact pursue happiness as the foundational consideration for his actions. In relation to Socrates’ emphasis on virtue, it is not entirely clear what that means. Virtue could be identical to happiness—in which case there is no difference between the two and if I am virtuous I am by definition happy—virtue could be a part of happiness—in which case if I am virtuous I will be happy although I could be made happier by the addition of other goods—or virtue could be instrumental for happiness—in which case if I am virtuous I might be happy (and I couldn’t be happy without virtue), but there is no guarantee that I will be happy.

There are a number of passages in the Apology that seem to indicate that the greatest good for a human being is having philosophical conversation (36b-d, 37e-38a, 40e-41c). Meno 87c-89a suggests that knowledge of the good guides the soul toward happiness (cf. Euthydemus 278e-282a). And at Gorgias 507a-c Socrates suggests that the virtuous person, acting in accordance with wisdom, attains happiness (cf. Gorgias 478c-e: the happiest person has no badness in his soul).

vi. Ruling is An Expertise

Socrates is committed to the theme that ruling is a kind of craft or art (technē). As such, it requires knowledge. Just as a doctor brings about a desired result for his patient—health, for instance—so the ruler should bring about some desired result in his subject (Republic 341c-d, 342c). Medicine, insofar as it has the best interest of its patient in mind, never seeks to benefit the practitioner. Similarly, the ruler’s job is to act not for his own benefit but for the benefit of the citizens of the political community. This is not to say that there might not be some contingent benefit that accrues to the practitioner; the doctor, for instance, might earn a fine salary. But this benefit is not intrinsic to the expertise of medicine as such. One could easily conceive of a doctor that makes very little money. One cannot, however, conceive of a doctor that does not act on behalf of his patient. Analogously, ruling is always for the sake of the ruled citizen, and justice, contra the famous claim from Thrasymachus, is not whatever is in the interest of the ruling power (Republic 338c-339a).

d. Socrates the Ironist

The suspicion that Socrates is an ironist can mean a number of things: on the one hand, it can indicate that Socrates is saying something with the intent to convey the opposite meaning. Some readers for instance, including a number in the ancient world, understood Socrates’ avowal of ignorance in precisely this way. Many have interpreted Socrates’ praise of Euthyphro, in which he claims that he can learn from him and will become his pupil, as an example of this sort of irony (Euthyphro 5a-b). On the other hand, the Greek word eirōneia was understood to carry with it a sense of subterfuge, rendering the sense of the word something like masking with the intent to deceive.

Additionally, there are a number of related questions about Socrates’ irony. Is the interlocutor supposed to be aware of the irony, or is he ignorant of it? Is it the job of the reader to discern the irony? Is the purpose of irony rhetorical, intended to maintain Socrates’ position as the director of the conversation, or pedagogical, meant to encourage the interlocutor to learn something? Could it be both?

Scholars disagree on the sense in which we ought to call Socrates ironic. When Socrates asks Callicles to tell him what he means by the stronger and to go easy on him so that he might learn better, Callicles claims he is being ironic (Gorgias 489e). Thrasymachus accuses Socrates of being ironic insofar as he pretends he does not have an account of justice, when he is actually hiding what he truly thinks (Republic 337a). And though the Symposium is generally not thought to be a “Socratic” dialogue, we there find Alcibiades accusing Socrates of being ironic insofar as he acts like he is interested in him but then deny his advances (Symposium 216e, 218d). It is not clear which kind of irony is at work with these examples.

Aristotle defines irony as an attempt at self-deprecation (Nicomachean Ethics 4.7, 1127b23-26). He argues that self-deprecation is the opposite of boastfulness, and people that engage in this sort of irony do so to avoid pompousness and make their characters more attractive. Above all, such people disclaim things that bring reputation. On this reading, Socrates was prone to understatement.

There are some thinkers for whom Socratic irony is not just restricted to what Socrates says. The 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard held the view that Socrates himself, his character, is ironic. The 20th century philosopher Leo Strauss defined irony as the noble dissimulation of one’s worth. On this reading, Socrates’ irony consisted in his refusal to display his superiority in front of his inferiors so that his message would be understood only by the privileged few. As such, Socratic irony is intended to conceal Socrates’ true message.

3. Method: How Did Socrates Do Philosophy?

As famous as the Socratic themes are, the Socratic method is equally famous. Socrates conducted his philosophical activity by means of question an answer, and we typically associate with him a method called the elenchus. At the same time, Plato’s Socrates calls himself a midwife—who has no ideas of his own but helps give birth to the ideas of others—and proceeds dialectically—defined either as asking questions, embracing the practice of collection and division, or proceeding from hypotheses to first principles.

a. The Elenchus: Socrates the Refuter

A typical Socratic elenchus is a cross-examination of a particular position, proposition, or definition, in which Socrates tests what his interlocutor says and refutes it. There is, however, great debate amongst scholars regarding not only what is being refuted but also whether or not the elenchus can prove anything. There are questions, in other words, about the topic of the elenchus and its purpose or goal.

i. Topic

Socrates typically begins his elenchus with the question, “what is it”? What is piety, he asks Euthyphro. Euthyphro appears to give five separate definitions of piety: piety is proceeding against whomever does injustice (5d-6e), piety is what is loved by the gods (6e-7a), piety is what is loved by all the gods (9e), the godly and the pious is the part of the just that is concerned with the care of the gods (12e), and piety is the knowledge of sacrificing and praying (13d-14a). For some commentators, what Socrates is searching for here is a definition. Other commentators argue that Socrates is searching for more than just the definition of piety but seeks a comprehensive account of the nature of piety. Whatever the case, Socrates refutes the answer given to him in response to the ‘what is it’ question.

Another reading of the Socratic elenchus is that Socrates is not just concerned with the reply of the interlocutor but is concerned with the interlocutor himself. According to this view, Socrates is as much concerned with the truth or falsity of propositions as he is with the refinement of the interlocutor’s way of life. Socrates is concerned with both epistemological and moral advances for the interlocutor and himself. It is not propositions or replies alone that are refuted, for Socrates does not conceive of them dwelling in isolation from those that hold them. Thus conceived, the elenchus refutes the person holding a particular view, not just the view. For instance, Socrates shames Thrasymachus when he shows him that he cannot maintain his view that justice is ignorance and injustice is wisdom (Republic I 350d). The elenchus demonstrates that Thrasymachus cannot consistently maintain all his claims about the nature of justice. This view is consistent with a view we find in Plato’s late dialogue called the Sophist, in which the Visitor from Elea, not Socrates, claims that the soul will not get any advantage from learning that it is offered to it until someone shames it by refuting it (230b-d).

ii. Purpose

In terms of goal, there are two common interpretations of the elenchus. Both have been developed by scholars in response to what Gregory Vlastos called the problem of the Socratic elenchus. The problem is how Socrates can claim that position W is false, when the only thing he has established is its inconsistency with other premises whose truth he has not tried to establish in the elenchus.

The first response is what is called the constructivist position. A constructivist argues that the elenchus establishes the truth or falsity of individual answers. The elenchus on this interpretation can and does have positive results. Vlastos himself argued that Socrates not only established the inconsistency of the interlocutor’s beliefs by showing their inconsistency, but that Socrates’ own moral beliefs were always consistent, able to withstand the test of the elenchus. Socrates could therefore pick out a faulty premise in his elenctic exchange with an interlocutor, and sought to replace the interlocutor’s false beliefs with his own.

The second response is called the non-constructivist position. This position claims that Socrates does not think the elenchus can establish the truth or falsity of individual answers. The non-constructivist argues that all the elenchus can show is the inconsistency of W with the premises X, Y, and Z. It cannot establish that ~W is the case, or for that matter replace any of the premises with another, for this would require a separate argument. The elenchus establishes the falsity of the conjunction of W, X, Y, and Z, but not the truth or falsity of any of those premises individually. The purpose of the elenchus on this interpretation is to show the interlocutor that he is confused, and, according to some scholars, to use that confusion as a stepping stone on the way to establishing a more consistent, well-formed set of beliefs.

b. Maieutic: Socrates the Midwife

In Plato’s Theaetetus Socrates identifies himself as a midwife (150b-151b). While the dialogue is not generally considered Socratic, it is elenctic insofar as it tests and refutes Theaetetus’ definitions of knowledge. It also ends without a conclusive answer to its question, a characteristic it shares with a number of Socratic dialogues.

Socrates tells Theaetetus that his mother Phaenarete was a midwife (149a) and that he himself is an intellectual midwife. Whereas the craft of midwifery (150b-151d) brings on labor pains or relieves them in order to help a woman deliver a child, Socrates does not watch over the body but over the soul, and helps his interlocutor give birth to an idea. He then applies the elenchus to test whether or not the intellectual offspring is a phantom or a fertile truth. Socrates stresses that both he and actual midwives are barren, and cannot give birth to their own offspring. In spite of his own emptiness of ideas, Socrates claims to be skilled at bringing forth the ideas of others and examining them.

c. Dialectic: Socrates the Constructer

The method of dialectic is thought to be more Platonic than Socratic, though one can understand why many have associated it with Socrates himself. For one thing, the Greek dialegesthai ordinarily means simply “to converse” or “to discuss.” Hence when Socrates is distinguishing this sort of discussion from rhetorical exposition in the Gorgias, the contrast seems to indicate his preference for short questions and answers as opposed to longer speeches (447b-c, 448d-449c).

There are two other definitions of dialectic in the Platonic corpus. First, in the Republic, Socrates distinguishes between dianoetic thinking, which makes use of the senses and assumes hypotheses, and dialectical thinking, which does not use the senses and goes beyond hypotheses to first principles (Republic VII 510c-511c, 531d-535a). Second, in the Phaedrus, Sophist, Statesman, and Philebus, dialectic is defined as a method of collection and division. One collects things that are scattered into one kind and also divides each kind according to its species (Phaedrus 265d-266c).

Some scholars view the elenchus and dialectic as fundamentally different methods with different goals, while others view them as consistent and reconcilable. Some even view them as two parts of one argument procedure, in which the elenchus refutes and dialectic constructs.

4. Legacy: How Have Other Philosophers Understood Socrates?

Nearly every school of philosophy in antiquity had something positive to say about Socrates, and most of them drew their inspiration from him. Socrates also appears in the works of many famous modern philosophers. Immanuel Kant, the 18th century German philosopher best known for the categorical imperative, hailed Socrates, amongst other ancient philosophers, as someone who didn’t just speculate but who lived philosophically. One of the more famous quotes about Socrates is from John Stuart Mill, the 19th century utilitarian philosopher who claimed that it is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. The following is but a brief survey of Socrates as he is treated in philosophical thinking that emerges after the death of Aristotle in 322 B.C.E.

a. Hellenistic Philosophy

i. The Cynics

The Cynics greatly admired Socrates, and traced their philosophical lineage back to him. One of the first representatives of the Socratic legacy was the Cynic Diogenes of Sinope. No genuine writings of Diogenes have survived and most of our evidence about him is anecdotal. Nevertheless, scholars attribute a number of doctrines to him. He sought to undermine convention as a foundation for ethical values and replace it with nature. He understood the essence of human being to be rational, and defined happiness as freedom and self-mastery, an objective readily accessible to those who trained the body and mind.

ii. The Stoics

There is a biographical story according to which Zeno, the founder of the Stoic school and not the Zeno of Zeno's Paradoxes, became interested in philosophy by reading and inquiring about Socrates. The Stoics took themselves to be authentically Socratic, especially in defending the unqualified restriction of ethical goodness to ethical excellence, the conception of ethical excellence as a kind of knowledge, a life not requiring any bodily or external advantage nor ruined by any bodily disadvantage, and the necessity and sufficiency of ethical excellence for complete happiness.

Zeno is known for his characterization of the human good as a smooth flow of life. Stoics were therefore attracted to the Socratic elenchus because it could expose inconsistencies—both social and psychological—that disrupted one’s life. In the absence of justification for a specific action or belief, one would not be in harmony with oneself, and therefore would not live well. On the other hand, if one held a position that survived cross-examination, such a position would be consistent and coherent. The Socratic elenchus was thus not just an important social and psychological test, but also an epistemological one. The Stoics held that knowledge was a coherent set of psychological attitudes, and therefore a person holding attitudes that could withstand the elenchus could be said to have knowledge. Those with inconsistent or incoherent psychological commitments were thought to be ignorant.

Socrates also figures in Roman Stoicism, particularly in the works of Seneca and Epictetus. Both men admired Socrates’ strength of character. Seneca praises Socrates for his ability to remain consistent unto himself in the face of the threat posed by the Thirty Tyrants, and also highlights the Socratic focus on caring for oneself instead of fleeing oneself and seeking fulfillment by external means. Epictetus, when offering advice about holding to one’s own moral laws as inviolable maxims, claims, “though you are not yet a Socrates, you ought, however, to live as one desirous of becoming a Socrates” (Enchiridion 50).

One aspect of Socrates to which Epictetus was particularly attracted was the elenchus. Though his understanding of the process is in some ways different from Socrates’, throughout his Discourses Epictetus repeatedly stresses the importance of recognition of one’s ignorance (2.17.1) and awareness of one’s own impotence regarding essentials (2.11.1). He characterizes Socrates as divinely appointed to hold the elenctic position (3.21.19) and associates this role with Socrates’ protreptic expertise (2.26.4-7). Epictetus encouraged his followers to practice the elenchus on themselves, and claims that Socrates did precisely this on account of his concern with self-examination (2.1.32-3).

iii. The Skeptics

Broadly speaking, skepticism is the view that we ought to be either suspicious of claims to epistemological truth or at least withhold judgment from affirming absolute claims to knowledge. Amongst Pyrrhonian skeptics, Socrates appears at times like a dogmatist and at other times like a skeptic or inquirer. On the one hand, Sextus Empiricus lists Socrates as a thinker who accepts the existence of god (Against the Physicists, I.9.64) and then recounts the cosmological argument that Xenophon attributes to Socrates (Against the Physicists, I.9.92-4). On the other hand, in arguing that human being is impossible to conceive, Sextus Empiricus cites Socrates as unsure whether or not he is a human being or something else (Outlines of Pyrrhonism 2.22). Socrates is also said to have remained in doubt about this question (Against the Professors 7.264).

Academic skeptics grounded their position that nothing can be known in Socrates’ admission of ignorance in the Apology (Cicero, On the Orator 3.67, Academics 1.44). Arcesilaus, the first head of the Academy to take it toward a skeptical turn, picked up from Socrates the procedure of arguing, first asking others to give their positions and then refuting them (Cicero, On Ends 2.2, On the Orator 3.67, On the Nature of the Gods 1.11). While the Academy would eventually move away from skepticism, Cicero, speaking on behalf of the Academy of Philo, makes the claim that Socrates should be understood as endorsing the claim that nothing, other than one’s own ignorance, could be known (Academics 2.74).

iv. The Epicurean

The Epicureans were one of the few schools that criticized Socrates, though many scholars think that this was in part because of their animus toward their Stoic counterparts, who admired him. In general, Socrates is depicted in Epicurean writings as a sophist, rhetorician, and skeptic who ignored natural science for the sake of ethical inquiries that concluded without answers. Colotes criticizes Socrates’ statement in the Phaedrus (230a) that he does not know himself (Plutarch, Against Colotes 21 1119b), and Philodemus attacks Socrates’ argument in the Protagoras (319d) that virtue cannot be taught (Rhetoric I 261, 8ff).

The Epicureans wrote a number of books against several of Plato’s Socratic dialogues, including the Lysis, Euthydemus, and Gorgias. In the Gorgias we find Socrates suspicious of the view that pleasure is intrinsically worthy and his insistence that pleasure is not the equivalent of the good (Gorgias 495b-499b). In defining pleasure as freedom from disturbance (ataraxia) and defining this sort of pleasure as the sole good for human beings, the Epicureans shared little with the unbridled hedonism Socrates criticizes Callicles for embracing. Indeed, in the Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus explicitly argues against pursuing this sort of pleasure (131-132). Nonetheless, the Epicureans did equate pleasure with the good, and the view that pleasure is not the equivalent of the good could not have endeared Socrates to their sentiment.

Another reason for the Epicurean refusal to praise Socrates or make him a cornerstone of their tradition was his perceived irony. According to Cicero, Epicurus was opposed to Socrates’ representing himself as ignorant while simultaneously praising others like Protagoras, Hippias, Prodicus, and Gorgias (Rhetoric, Vol. II, Brutus 292). This irony for the Epicureans was pedagogically pointless: if Socrates had something to say, he should have said it instead of hiding it.

v. The Peripatetics

Aristotle’s followers, the Peripatetics, either said little about Socrates or were pointedly vicious in their attacks. Amongst other things, the Peripatetics accused Socrates of being a bigamist, a charge that appears to have gained so much traction that the Stoic Panaetius wrote a refutation of it (Plutarch, Aristides 335c-d). The general peripatetic criticism of Socrates, similar in one way to the Epicureans, was that he concentrated solely on ethics, and that this was an unacceptable ideal for the philosophical life.

b. Modern Philosophy

i. Hegel

In Socrates, Hegel found what he called the great historic turning point (Philosophy of History, 448). With Socrates, Hegel claims, two opposed rights came into collision: the individual consciousness and the universal law of the state. Prior to Socrates, morality for the ancients was present but it was not present Socratically. That is, the good was present as a universal, without its having had the form of the conviction of the individual in his consciousness (407). Morality was present as an immediate absolute, directing the lives of citizens without their having reflected upon it and deliberated about it for themselves. The law of the state, Hegel claims, had authority as the law of the gods, and thus had a universal validity that was recognized by all (408).

In Hegel’s view the coming of Socrates signals a shift in the relationship between the individual and morality. The immediate now had to justify itself to the individual consciousness. Hegel thus not only ascribes to Socrates the habit of asking questions about what one should do but also about the actions that the state has prescribed. With Socrates, consciousness is turned back within itself and demands that the law should establish itself before consciousness, internal to it, not merely outside it (408-410). Hegel attributes to Socrates a reflective questioning that is skeptical, which moves the individual away from unreflective obedience and into reflective inquiry about the ethical standards of one’s community.

Generally, Hegel finds in Socrates a skepticism that renders ordinary or immediate knowledge confused and insecure, in need of reflective certainty which only consciousness can bring (370). Though he attributes to the sophists the same general skeptical comportment, in Socrates Hegel locates human subjectivity at a higher level. With Socrates and onward we have the world raising itself to the level of conscious thought and becoming object for thought. The question as to what Nature is gives way to the question about what Truth is, and the question about the relationship of self-conscious thought to real essence becomes the predominant philosophical issue (450-1).

ii. Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard’s most well recognized views on Socrates are from his dissertation, The Concept of Irony With Continual Reference to Socrates. There, he argues that Socrates is not the ethical figure that the history of philosophy has thought him to be, but rather an ironist in all that he does. Socrates does not just speak ironically but is ironic. Indeed, while most people have found Aristophanes’ portrayal of Socrates an obvious exaggeration and caricature, Kierkegaard goes so far as to claim that he came very close to the truth in his depiction of Socrates. He rejects Hegel’s picture of Socrates ushering in a new era of philosophical reflection and instead argues that the limits of Socratic irony testified to the need for religious faith. As opposed to the Hegelian view that Socratic irony was an instrument in the service of the development of self-consciousness, Kierkegaard claims that irony was Socrates’ position or comportment, and that he did not have any more than this to give.