About John Duns Scotus

March 17, 2017

About Francis Bacon

March 20, 2017Renaissance Thought

About Niccolo Machiavelli

N iccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy, on May 3, 1469—a time when Italy was divided into four rival city-states and, thusly, was at the mercy of stronger governments throughout the rest of Europe.

The young Niccolò Machiavelli became a diplomat after the temporary fall of Florence's ruling Medici family in 1494. He served in that position for 14 years in Italy's Florentine Republic during the Medici family's exile, during which time he earned a reputation for deviousness, enjoying shocking his associates by appearing more shameless than he truly was.

After his involvement in an unsuccessful attempt to organize a Florentine militia against the return of the Medici family to power in 1512 became known, Machiavelli was tortured, jailed and banished from an active role in political life.

In his later years, Niccolò Machiavelli resided in a small village just outside of Florence. He died in the city on June 21, 1527. His tomb is in the church of Santa Croce in Florence, which, ironically, he had been banned from entering during the last years of his life. Today, Machiavelli is regarded as the "father of modern political theory."

1. Life and Works

a. Life

Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy, the third child and first son of attorney Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli and his wife, Bartolomea di Stefano Nelli.The Machiavelli family is believed to be descended from the old marquesses of Tuscany and to have produced thirteen Florentine Gonfalonieres of Justice,one of the offices of a group of nine citizens selected by drawing lots every two months and who formed the government, or Signoria; but he was never a full citizen of Florence because of the nature of Florentine citizenship in that time even under the republican regime. Machiavelli married Marietta Corsini in 1502.

Machiavelli was born in a tumultuous era in which popes waged acquisitive wars against Italian city-states, and people and cities often fell from power as France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, and Switzerland battled for regional influence and control. Political-military alliances continually changed, featuring condottieri (mercenary leaders), who changed sides without warning, and the rise and fall of many short-lived governments.

Machiavelli was taught grammar, rhetoric, and Latin. It is thought that he did not learn Greek even though Florence was at the time one of the centres of Greek scholarship in Europe. In 1494 Florence restored the republic, expelling the Medici family that had ruled Florence for some sixty years. Shortly after the execution of Savonarola, Machiavelli was appointed to an office of the second chancery, a medieval writing office that put Machiavelli in charge of the production of official Florentine government documents. Shortly thereafter, he was also made the secretary of the Dieci di Libertà e Pace.

In the first decade of the sixteenth century, he carried out several diplomatic missions: most notably to the Papacy in Rome. Moreover, from 1502 to 1503, he witnessed the brutal reality of the state-building methods of Cesare Borgia (1475–1507) and his father, Pope Alexander VI, who were then engaged in the process of trying to bring a large part of Central Italy under their possession. The pretext of defending Church interests was used as a partial justification by the Borgias. Other excursions to the court of Louis XII and the Spanish court influenced his writings such as The Prince.

Between 1503 and 1506, Machiavelli was responsible for the Florentine militia. He distrusted mercenaries (a distrust that he explained in his official reports and then later in his theoretical works for their unpatriotic and uninvested nature in the war that makes their allegiance fickle and often too unreliable when most needed) and instead staffed his army with citizens, a policy that was to be repeatedly successful. Under his command, Florentine citizen-soldiers defeated Pisa in 1509.

However, Machiavelli's success did not last. In August 1512 the Medici, backed by Pope Julius II used Spanish troops to defeat the Florentines at Prato, but many historians have argued that it was due to Piero Soderini's unwillingness to compromise with the Medici, who were holding Prato under siege. In the wake of the siege, Soderini resigned as Florentine head of state and left in exile. The experience would, like Machiavelli's time in foreign courts and with the Borgia, heavily influence his political writings.

After the Medici victory, the Florentine city-state and the republic were dissolved, and Machiavelli was deprived of office in 1512. In 1513 the Medici accused him of conspiracy against them and had him imprisoned. Despite having been subjected to torture ("with the rope" in which the prisoner is hanged from his bound wrists, from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body's weight and dislocating the shoulders), he denied involvement and was released after three weeks.

Machiavelli then retired to his estate at Sant'Andrea in Percussina, near San Casciano in Val di Pesa, and devoted himself to studying and writing of the political treatises that earned his place in the intellectual development of political philosophy and political conduct.

Despairing of the opportunity to remain directly involved in political matters, after a time, he began to participate in intellectual groups in Florence and wrote several plays that (unlike his works on political theory) were both popular and widely known in his lifetime. Still, politics remained his main passion and, to satisfy this interest, he maintained a well-known correspondence with more politically connected friends, attempting to become involved once again in political life.

In a letter to Francesco Vettori, he described his exile:

When evening comes, I go back home, and go to my study. On the threshold, I take off my work clothes, covered in mud and filth, and I put on the clothes an ambassador would wear. Decently dressed, I enter the ancient courts of rulers who have long since died. There, I am warmly welcomed, and I feed on the only food I find nourishing and was born to savour. I am not ashamed to talk to them and ask them to explain their actions and they, out of kindness, answer me. Four hours go by without my feeling any anxiety. I forget every worry. I am no longer afraid of poverty or frightened of death. I live entirely through them.

Machiavelli died in 1527 at 58 after receiving his last rites. He was buried at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. An epitaph honouring him is inscribed on his monument. The Latin legend reads: TANTO NOMINI NULLUM PAR ELOGIUM ("So great a name (has) no adequate praise" or "No eulogy (would be) a match for such a great name").

b. Works

The Prince

Machiavelli's best-known book Il Principe contains several maxims concerning politics. Instead of the more traditional target audience of a hereditary prince, it concentrates on the possibility of a "new prince". To retain power, the hereditary prince must carefully balance the interests of a variety of institutions to which the people are accustomed. By contrast, a new prince has the more difficult task in ruling: He must first stabilise his newfound power in order to build an enduring political structure. Machiavelli suggests that the social benefits of stability and security can be achieved in the face of moral corruption. Machiavelli believed that public and private morality had to be understood as two different things in order to rule well. As a result, a ruler must be concerned not only with reputation, but also must be positively willing to act immorally at the right times. Machiavelli believed as a ruler, it was better to be widely feared than to be greatly loved; A loved ruler retains authority by obligation while a feared leader rules by fear of punishment. As a political theorist, Machiavelli emphasized the occasional need for the methodical exercise of brute force or deceit including extermination of entire noble families to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince's authority.

Scholars often note that Machiavelli glorifies instrumentality in state building, an approach embodied by the saying "The ends justify the means." It should be noted that this quote has been disputed and may not come from Niccolò Machiavelli or his writings. Violence may be necessary for the successful stabilisation of power and introduction of new legal institutions. Force may be used to eliminate political rivals, to coerce resistant populations, and to purge the community of other men strong enough of a character to rule, who will inevitably attempt to replace the ruler. Machiavelli has become infamous for such political advice, ensuring that he would be remembered in history through the adjective, "Machiavellian".

Notwithstanding some mitigating themes, the Catholic Church banned The Prince, putting it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. Humanists also viewed the book negatively, including Erasmus of Rotterdam. As a treatise, its primary intellectual contribution to the history of political thought is the fundamental break between political realism and political idealism, due to it being a manual on acquiring and keeping political power. In contrast with Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli insisted that an imaginary ideal society is not a model by which a prince should orient himself.

Concerning the differences and similarities in Machiavelli's advice to ruthless and tyrannical princes in The Prince and his more republican exhortations in Discourses on Livy, many have concluded that The Prince, although written as advice for a monarchical prince, contains arguments for the superiority of republican regimes, similar to those found in the Discourses. In the 18th century, the work was even called a satire, for example by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. More recently, commentators such as Leo Strauss and Harvey Mansfield have agreed that The Prince can be read as having a deliberate comical irony.

Other interpretations include for example that of Antonio Gramsci, who argued that Machiavelli's audience for this work was not even the ruling class but the common people because the rulers already knew these methods through their education.

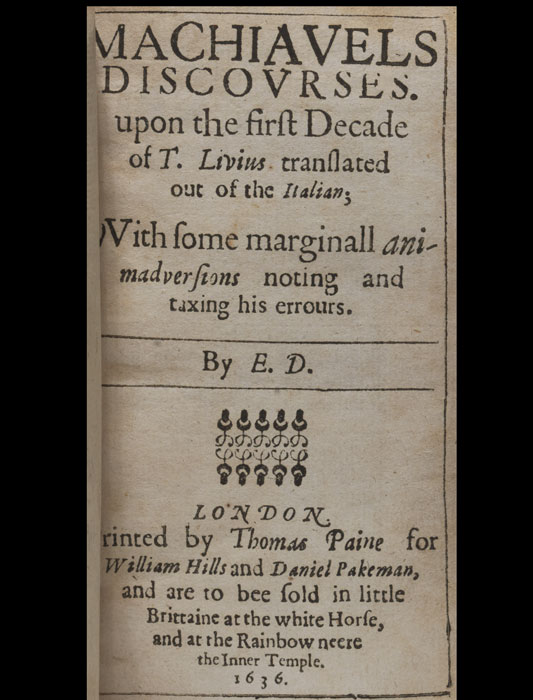

Discourses on Livy

The Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy, published in 1531, written 1517, often referred to simply as the "Discourses" or Discorsi, is nominally a discussion regarding the classical history of early Ancient Rome although it strays very far from this subject matter and also uses contemporary political examples to illustrate points. Machiavelli presents it as a series of lessons on how a republic should be started and structured. It is a larger work than The Prince, and while it more openly explains the advantages of republics, it also contains many similar themes. Commentators disagree about how much the two works agree with each other, frequently referring to leaders of democracies as "princes". It includes early versions of the concept of checks and balances and asserts the superiority of a republic over a principality. It became one of the central texts of republicanism, and has often been argued to be a superior work to The Prince.

From The Discourses:

- "In fact, when there is combined under the same constitution a prince, a nobility, and the power of the people, then these three powers will watch and keep each other reciprocally in check." Book I, Chapter II

- "Doubtless these means [of attaining power] are cruel and destructive of all civilised life, and neither Christian, nor even human, and should be avoided by everyone. In fact, the life of a private citizen would be preferable to that of a king at the expense of the ruin of so many human beings." Book I, Chapter XXVI

- "Now, in a well-ordered republic, it should never be necessary to resort to extra-constitutional measures. ..." Book I, Chapter XXXIV

- "... the governments of the people are better than those of princes." Book I, Chapter LVIII

- "... if we compare the faults of a people with those of princes, as well as their respective good qualities, we shall find the people vastly superior in all that is good and glorious". Book I, Chapter LVIII

- "For government consists mainly in so keeping your subjects that they shall be neither able nor disposed to injure you. ..." Book II, Chapter XXIII

- "... no prince is ever benefited by making himself hated." Book III, Chapter XIX

- "Let not princes complain of the faults committed by the people subjected to their authority, for they result entirely from their own negligence or bad example." Book III, Chapter XXIX

2. Beliefs

Empiricism and realism versus idealism

Machiavelli is sometimes seen as the prototype of a modern empirical scientist, building generalizations from experience and historical facts, and emphasizing the uselessness of theorizing with the imagination.

He emancipated politics from theology and moral philosophy. He undertook to describe simply what rulers actually did and thus anticipated what was later called the scientific spirit in which questions of good and bad are ignored, and the observer attempts to discover only what really happens.

— Joshua Kaplan, 2005

Machiavelli felt that his early schooling along the lines of a traditional classical education was essentially useless for the purpose of understanding politics. Nevertheless, he advocated intensive study of the past, particularly regarding the founding of a city, which he felt was a key to understanding its later development. Moreover, he studied the way people lived and aimed to inform leaders how they should rule and even how they themselves should live. For example, Machiavelli denies that living virtuously necessarily leads to happiness. And Machiavelli viewed misery as one of the vices that enables a prince to rule. Machiavelli stated that it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved. In much of Machiavelli's work, it seems that the ruler must adopt unsavory policies for the sake of the continuance of his regime.

A related and more controversial proposal often made is that he described how to do things in politics in a way which seemed neutral concerning who used the advice—tyrants or good rulers. That Machiavelli strove for realism is not doubted, but for four centuries scholars have debated how best to describe his morality. The Prince made the word "Machiavellian" a byword for deceit, despotism, and political manipulation. Even if Machiavelli was not himself evil, Leo Strauss declared himself inclined toward the traditional view that Machiavelli was self-consciously a "teacher of evil," since he counsels the princes to avoid the values of justice, mercy, temperance, wisdom, and love of their people in preference to the use of cruelty, violence, fear, and deception. Italian anti-fascist philosopher Benedetto Croce (1925) concludes Machiavelli is simply a "realist" or "pragmatist" who accurately states that moral values in reality do not greatly affect the decisions that political leaders make. German philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1946) held that Machiavelli simply adopts the stance of a political scientist—a Galileo of politics—in distinguishing between the "facts" of political life and the "values" of moral judgment. On the other hand, Walter Russell Mead has argued that The Prince's advice presupposes the importance of ideas like legitimacy in making changes to the political system.

Fortune

Machiavelli is generally seen as being critical of Christianity as it existed in his time, specifically its effect upon politics, and also everyday life. In his opinion, Christianity, along with the teleological Aristotelianism that the church had come to accept, allowed practical decisions to be guided too much by imaginary ideals and encouraged people to lazily leave events up to providence or, as he would put it, chance, luck or fortune. While Christianity sees modesty as a virtue and pride as sinful, Machiavelli took a more classical position, seeing ambition, spiritedness, and the pursuit of glory as good and natural things, and part of the virtue and prudence that good princes should have. Therefore, while it was traditional to say that leaders should have virtues, especially prudence, Machiavelli's use of the words virtù and prudenza was unusual for his time, implying a spirited and immodest ambition. Famously, Machiavelli argued that virtue and prudence can help a man control more of his future, in the place of allowing fortune to do so.

Najemy (1993) has argued that this same approach can be found in Machiavelli's approach to love and desire, as seen in his comedies and correspondence. Najemy shows how Machiavelli's friend Vettori argued against Machiavelli and cited a more traditional understanding of fortune.

On the other hand, humanism in Machiavelli's time meant that classical pre-Christian ideas about virtue and prudence, including the possibility of trying to control one's future, were not unique to him. But humanists did not go so far as to promote the extra glory of deliberately aiming to establish a new state, in defiance of traditions and laws.

While Machiavelli's approach had classical precedents, it has been argued that it did more than just bring back old ideas and that Machiavelli was not a typical humanist. Strauss (1958) argues that the way Machiavelli combines classical ideas is new. While Xenophon and Plato also described realistic politics and were closer to Machiavelli than Aristotle was, they, like Aristotle, also saw Philosophy as something higher than politics. Machiavelli was apparently a materialist who objected to explanations involving formal and final causation, or teleology.

Machiavelli's promotion of ambition among leaders while denying any higher standard meant that he encouraged risk-taking, and innovation, most famously the founding of new modes and orders. His advice to princes was therefore certainly not limited to discussing how to maintain a state. It has been argued that Machiavelli's promotion of innovation led directly to the argument for progress as an aim of politics and civilisation. But while a belief that humanity can control its own future, control nature, and "progress" has been long lasting, Machiavelli's followers, starting with his own friend Guicciardini, have tended to prefer peaceful progress through economic development, and not warlike progress. As Harvey Mansfield (1995, p. 74) wrote: "In attempting other, more regular and scientific modes of overcoming fortune, Machiavelli's successors formalised and emasculated his notion of virtue."

Machiavelli however, along with some of his classical predecessors, saw ambition and spiritedness, and therefore war, as inevitable and part of human nature.

Strauss concludes his 1958 Thoughts on Machiavelli by proposing that this promotion of progress leads directly to the modern arms race. Strauss argued that the unavoidable nature of such arms races, which have existed before modern times and led to the collapse of peaceful civilisations, provides us with both an explanation of what is most truly dangerous in Machiavelli's innovations, but also the way in which the aims of his apparently immoral innovation can be understood.

Religion

Machiavelli explains repeatedly that religion is man-made, and that the value of religion lies in its contribution to social order and the rules of morality must be dispensed with if security requires it. In The Prince, the Discourses, and in the Life of Castruccio Castracani, he describes "prophets", as he calls them, like Moses, Romulus, Cyrus the Great, and Theseus (he treated pagan and Christian patriarchs in the same way) as the greatest of new princes, the glorious and brutal founders of the most novel innovations in politics, and men whom Machiavelli assures us have always used a large amount of armed force and murder against their own people. He estimated that these sects last from 1,666 to 3,000 years each time, which, as pointed out by Leo Strauss, would mean that Christianity became due to start finishing about 150 years after Machiavelli. Machiavelli's concern with Christianity as a sect was that it makes men weak and inactive, delivering politics into the hands of cruel and wicked men without a fight.

While fear of God can be replaced by fear of the prince, if there is a strong enough prince, Machiavelli felt that having a religion is in any case especially essential to keeping a republic in order. For Machiavelli, a truly great prince can never be conventionally religious himself, but he should make his people religious if he can. According to Strauss (1958, pp. 226–227) he was not the first person to ever explain religion in this way, but his description of religion was novel because of the way he integrated this into his general account of princes.

Machiavelli's judgment that democracies need religion for practical political reasons was widespread among modern proponents of republics until approximately the time of the French revolution. This therefore represents a point of disagreement between himself and late modernity.

Positive side to factional and individual vice

Despite the classical precedents, which Machiavelli was not the only one to promote in his time, Machiavelli's realism and willingness to argue that good ends justify bad things, is seen as a critical stimulus towards some of the most important theories of modern politics.

Firstly, particularly in the Discourses on Livy, Machiavelli is unusual in the positive side he sometimes seems to describe in factionalism in republics. For example, quite early in the Discourses, (in Book I, chapter 4), a chapter title announces that the disunion of the plebs and senate in Rome "kept Rome free." That a community has different components whose interests must be balanced in any good regime is an idea with classical precedents, but Machiavelli's particularly extreme presentation is seen as a critical step towards the later political ideas of both a division of powers or checks and balances, ideas which lay behind the US constitution, as well as many other modern state constitutions.

Similarly, the modern economic argument for capitalism, and most modern forms of economics, was often stated in the form of "public virtue from private vices." Also in this case, even though there are classical precedents, Machiavelli's insistence on being both realistic and ambitious, not only admitting that vice exists but being willing to risk encouraging it, is a critical step on the path to this insight.

Mansfield however argues that Machiavelli's own aims have not been shared by those he influenced. Machiavelli argued against seeing mere peace and economic growth as worthy aims on their own, if they would lead to what Mansfield calls the "taming of the prince."

3. Influence

Machiavelli's ideas had a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern west, helped by the new technology of the printing press. During the first generations after Machiavelli, his main influence was in non-Republican governments. Pole reported that The Prince was spoken of highly by Thomas Cromwell in England and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism, and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace. A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V. In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de' Medici and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. As Bireley (1990:17) reports, in the 16th century, Catholic writers "associated Machiavelli with the Protestants, whereas Protestant authors saw him as Italian and Catholic". In fact, he was apparently influencing both Catholic and Protestant kings.

One of the most important early works dedicated to criticism of Machiavelli, especially The Prince, was that of the Huguenot, Innocent Gentillet, whose work commonly referred to as Discourse against Machiavelli or Anti Machiavel was published in Geneva in 1576. He accused Machiavelli of being an atheist and accused politicians of his time by saying that his works were the "Koran of the courtiers", that "he is of no reputation in the court of France which hath not Machiavel's writings at the fingers ends". Another theme of Gentillet was more in the spirit of Machiavelli himself: he questioned the effectiveness of immoral strategies (just as Machiavelli had himself done, despite also explaining how they could sometimes work). This became the theme of much future political discourse in Europe during the 17th century. This includes the Catholic Counter Reformation writers summarised by Bireley: Giovanni Botero, Justus Lipsius, Carlo Scribani, Adam Contzen, Pedro de Ribadeneira, and Diego Saavedra Fajardo. These authors criticized Machiavelli, but also followed him in many ways. They accepted the need for a prince to be concerned with reputation, and even a need for cunning and deceit, but compared to Machiavelli, and like later modernist writers, they emphasized economic progress much more than the riskier ventures of war. These authors tended to cite Tacitus as their source for realist political advice, rather than Machiavelli, and this pretense came to be known as "Tacitism". "Black tacitism" was in support of princely rule, but "red tacitism" arguing the case for republics, more in the original spirit of Machiavelli himself, became increasingly important.

Modern materialist philosophy developed in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, starting in the generations after Machiavelli. This philosophy tended to be republican, more in the original spirit of Machiavellian, but as with the Catholic authors Machiavelli's realism and encouragement of using innovation to try to control one's own fortune were more accepted than his emphasis upon war and politics. Not only was innovative economics and politics a result, but also modern science, leading some commentators to say that the 18th century Enlightenment involved a "humanitarian" moderating of Machiavellianism.

The importance of Machiavelli's influence is notable in many important figures in this endeavor, for example Bodin, Francis Bacon,Algernon Sidney, Harrington, John Milton, Spinoza, Rousseau, Hume, Edward Gibbon, and Adam Smith. Although he was not always mentioned by name as an inspiration, due to his controversy, he is also thought to have been an influence for other major philosophers, such as Montaigne, Descartes, Hobbes, Locke and Montesquieu.

Although Jean-Jacques Rousseau is associated with very different political ideas, it is important to view Machiavelli's work from different points of view rather than just the traditional notion. For example, Rousseau viewed Machiavelli's work as a satirical piece in which Machiavelli exposes the faults of a one-man rule rather than exalting amorality.

In the seventeenth century it was in England that Machiavelli's ideas were most substantially developed and adapted, and that republicanism came once more to life; and out of seventeenth-century English republicanism there were to emerge in the next century not only a theme of English political and historical reflection—of the writings of the Bolingbroke circle and of Gibbon and of early parliamentary radicals—but a stimulus to the Enlightenment in Scotland, on the Continent, and in America.

Scholars have argued that Machiavelli was a major indirect and direct influence upon the political thinking of the Founding Fathers of the United States due to his overwhelming favoritism of republicanism and the republic type of government. According to John McCormick, it is still very much debatable whether or not Machiavelli was "an advisor of tyranny or partisan of liberty." Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli's republicanism when they opposed what they saw as the emerging aristocracy that they feared Alexander Hamilton was creating with the Federalist Party. Hamilton learned from Machiavelli about the importance of foreign policy for domestic policy, but may have broken from him regarding how rapacious a republic needed to be in order to survive (George Washington was probably less influenced by Machiavelli). However, the Founding Father who perhaps most studied and valued Machiavelli as a political philosopher was John Adams, who profusely commented on the Italian's thought in his work, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America.

In his Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, John Adams praised Machiavelli, with Algernon Sidney and Montesquieu, as a philosophic defender of mixed government. For Adams, Machiavelli restored empirical reason to politics, while his analysis of factions was commendable. Adams likewise agreed with the Florentine that human nature was immutable and driven by passions. He also accepted Machiavelli's belief that all societies were subject to cyclical periods of growth and decay. For Adams, Machiavelli lacked only a clear understanding of the institutions necessary for good government.