About William James

April 3, 2017

About Soren Aabye Kierkegaard

April 4, 2017American Pragmatism

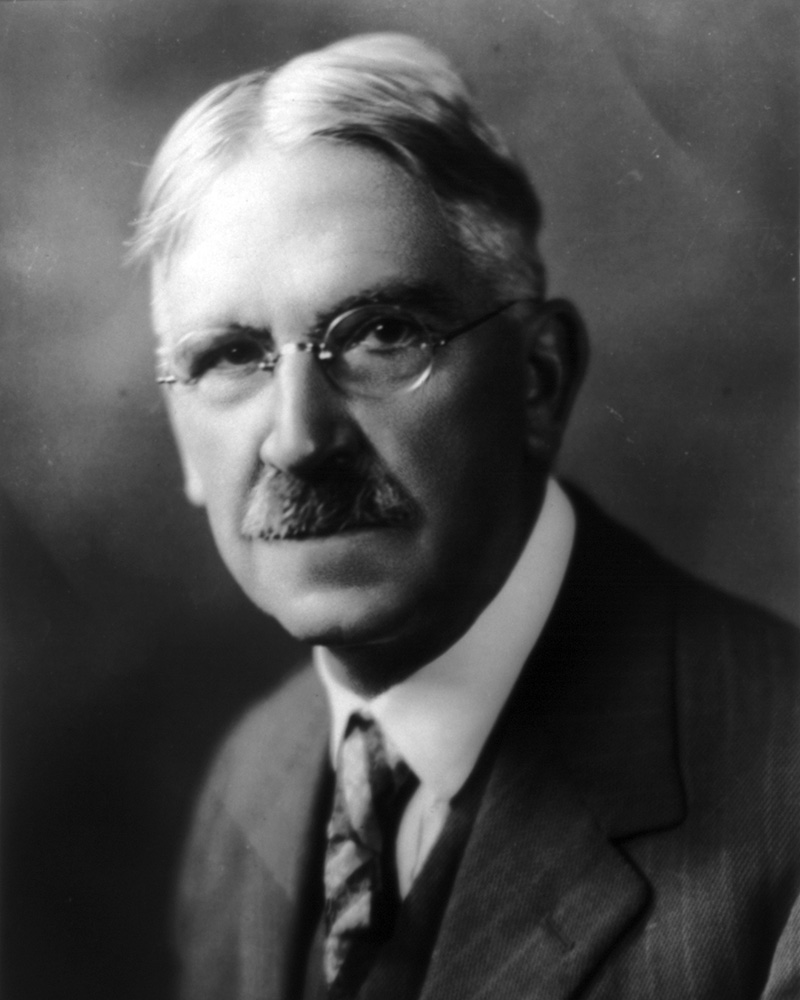

About John Dewey

J ohn Dewey was a leading proponent of the American school of thought known as pragmatism, a view that rejected the dualistic epistemology and metaphysics of modern philosophy in favor of a naturalistic approach that viewed knowledge as arising from an active adaptation of the human organism to its environment. On this view, inquiry should not be understood as consisting of a mind passively observing the world and drawing from this ideas that if true correspond to reality, but rather as a process which initiates with a check or obstacle to successful human action, proceeds to active manipulation of the environment to test hypotheses, and issues in a re-adaptation of organism to environment that allows once again for human action to proceed. With this view as his starting point, Dewey developed a broad body of work encompassing virtually all of the main areas of philosophical concern in his day. He also wrote extensively on social issues in such popular publications as the New Republic, thereby gaining a reputation as a leading social commentator of his time.

1. Life and Works

John Dewey was born on October 20, 1859, the third of four sons born to Archibald Sprague Dewey and Lucina Artemesia Rich of Burlington, Vermont. The eldest sibling died in infancy, but the three surviving brothers attended the public school and the University of Vermont in Burlington with John. While at the University of Vermont, Dewey was exposed to evolutionary theory through the teaching of G.H. Perkins and Lessons in Elementary Physiology, a text by T.H. Huxley, the famous English evolutionist. The theory of natural selection continued to have a life-long impact upon Dewey's thought, suggesting the barrenness of static models of nature, and the importance of focusing on the interaction between the human organism and its environment when considering questions of psychology and the theory of knowledge. The formal teaching in philosophy at the University of Vermont was confined for the most part to the school of Scottish realism, a school of thought that Dewey soon rejected, but his close contact both before and after graduation with his teacher of philosophy, H.A.P. Torrey, a learned scholar with broader philosophical interests and sympathies, was later accounted by Dewey himself as "decisive" to his philosophical development.

After graduation in 1879, Dewey taught high school for two years, during which the idea of pursuing a career in philosophy took hold. With this nascent ambition in mind, he sent a philosophical essay to W.T. Harris, then editor of the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, and the most prominent of the St. Louis Hegelians. Harris's acceptance of the essay gave Dewey the confirmation he needed of his promise as a philosopher. With this encouragement he traveled to Baltimore to enroll as a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University.

At Johns Hopkins Dewey came under the tutelage of two powerful and engaging intellects who were to have a lasting influence on him. George Sylvester Morris, a German-trained Hegelian philosopher, exposed Dewey to the organic model of nature characteristic of German idealism. G. Stanley Hall, one of the most prominent American experimental psychologists at the time, provided Dewey with an appreciation of the power of scientific methodology as applied to the human sciences. The confluence of these viewpoints propelled Dewey's early thought, and established the general tenor of his ideas throughout his philosophical career.

Upon obtaining his doctorate in 1884, Dewey accepted a teaching post at the University of Michigan, a post he was to hold for ten years, with the exception of a year at the University of Minnesota in 1888. While at Michigan Dewey wrote his first two books: Psychology (1887), and Leibniz's New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1888). Both works expressed Dewey's early commitment to Hegelian idealism, while the Psychology explored the synthesis between this idealism and experimental science that Dewey was then attempting to effect. At Michigan Dewey also met one of his important philosophical collaborators, James Hayden Tufts, with whom he would later author Ethics (1908; revised ed. 1932).

In 1894, Dewey followed Tufts to the recently founded University of Chicago. It was during his years at Chicago that Dewey's early idealism gave way to an empirically based theory of knowledge that was in concert with the then developing American school of thought known as pragmatism. This change in view finally coalesced into a series of four essays entitled collectively "Thought and its Subject-Matter," which was published along with a number of other essays by Dewey's colleagues and students at Chicago under the title Studies in Logical Theory (1903). Dewey also founded and directed a laboratory school at Chicago, where he was afforded an opportunity to apply directly his developing ideas on pedagogical method. This experience provided the material for his first major work on education, The School and Society (1899).

Disagreements with the administration over the status of the Laboratory School led to Dewey's resignation from his post at Chicago in 1904. His philosophical reputation now secured, he was quickly invited to join the Department of Philosophy at Columbia University. Dewey spent the rest of his professional life at Columbia. Now in New York, located in the midst of the Northeastern universities that housed many of the brightest minds of American philosophy, Dewey developed close contacts with many philosophers working from divergent points of view, an intellectually stimulating atmosphere which served to nurture and enrich his thought.

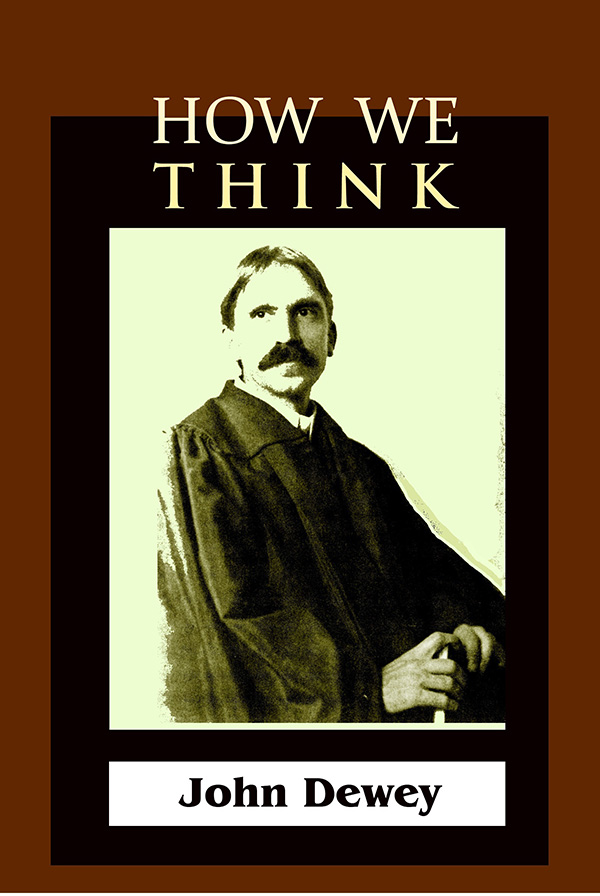

During his first decade at Columbia Dewey wrote a great number of articles in the theory of knowledge and metaphysics, many of which were published in two important books: The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy and Other Essays in Contemporary Thought (1910) and Essays in Experimental Logic(1916). His interest in educational theory also continued during these years, fostered by his work at Teachers College at Columbia. This led to the publication of How We Think (1910; revised ed. 1933), an application of his theory of knowledge to education, and Democracy and Education (1916), perhaps his most important work in the field.

During his years at Columbia Dewey's reputation grew not only as a leading philosopher and educational theorist, but also in the public mind as an important commentator on contemporary issues, the latter due to his frequent contributions to popular magazines such as The New Republic and Nation, as well as his ongoing political involvement in a variety of causes, such as women's suffrage and the unionization of teachers. One outcome of this fame was numerous invitations to lecture in both academic and popular venues. Many of his most significant writings during these years were the result of such lectures, includingReconstruction in Philosophy (1920), Human Nature and Conduct (1922), Experience and Nature(1925), The Public and its Problems (1927), and The Quest for Certainty (1929).

Dewey's retirement from active teaching in 1930 did not curtail his activity either as a public figure or productive philosopher. Of special note in his public life was his participation in the Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Against Leon Trotsky at the Moscow Trial, which exposed Stalin's political machinations behind the Moscow trials of the mid-1930s, and his defense of fellow philosopher Bertrand Russell against an attempt by conservatives to remove him from his chair at the College of the City of New York in 1940. A primary focus of Dewey's philosophical pursuits during the 1930s was the preparation of a final formulation of his logical theory, published as Logic: The Theory of Inquiry in 1938. Dewey's other significant works during his retirement years include Art as Experience (1934), A Common Faith(1934), Freedom and Culture (1939), Theory of Valuation (1939), and Knowing and the Known(1949), the last coauthored with Arthur F. Bentley. Dewey continued to work vigorously throughout his retirement until his death on June 2, 1952, at the age of ninety-two.

2. Theory of Knowledge

The central focus of Dewey's philosophical interests throughout his career was what has been traditionally called "epistemology," or the "theory of knowledge." It is indicative, however, of Dewey's critical stance toward past efforts in this area that he expressly rejected the term "epistemology," preferring the "theory of inquiry" or "experimental logic" as more representative of his own approach.

In Dewey's view, traditional epistemologies, whether rationalist or empiricist, had drawn too stark a distinction between thought, the domain of knowledge, and the world of fact to which thought purportedly referred: thought was believed to exist apart from the world, epistemically as the object of immediate awareness, ontologically as the unique aspect of the self. The commitment of modern rationalism, stemming from Descartes, to a doctrine of innate ideas, ideas constituted from birth in the very nature of the mind itself, had effected this dichotomy; but the modern empiricists, beginning with Locke, had done the same just as markedly by their commitment to an introspective methodology and a representational theory of ideas. The resulting view makes a mystery of the relevance of thought to the world: if thought constitutes a domain that stands apart from the world, how can its accuracy as an account of the world ever be established? For Dewey a new model, rejecting traditional presumptions, was wanting, a model that Dewey endeavored to develop and refine throughout his years of writing and reflection.

In his early writings on these issues, such as "Is Logic a Dualistic Science?" (1890) and "The Present Position of Logical Theory" (1891), Dewey offered a solution to epistemological issues mainly along the lines of his early acceptance of Hegelian idealism: the world of fact does not stand apart from thought, but is itself defined within thought as its objective manifestation. But during the succeeding decade Dewey gradually came to reject this solution as confused and inadequate.

A number of influences have bearing on Dewey's change of view. For one, Hegelian idealism was not conducive to accommodating the methodologies and results of experimental science which he accepted and admired. Dewey himself had attempted to effect such an accommodation between experimental psychology and idealism in his early Psychology (1887), but the publication of William James' Principles of Psychology (1891), written from a more thoroughgoing naturalistic stance, suggested the superfluity of idealist principles in the treatment of the subject.

Second, Darwin's theory of natural selection suggested in a more particular way the form which a naturalistic approach to the theory of knowledge should take. Darwin's theory had renounced supernatural explanations of the origins of species by accounting for the morphology of living organisms as a product of a natural, temporal process of the adaptation of lineages of organisms to their environments, environments which, Darwin understood, were significantly determined by the organisms that occupied them. The key to the naturalistic account of species was a consideration of the complex interrelationships between organisms and environments. In a similar way, Dewey came to believe that a productive, naturalistic approach to the theory of knowledge must begin with a consideration of the development of knowledge as an adaptive human response to environing conditions aimed at an active restructuring of these conditions. Unlike traditional approaches in the theory of knowledge, which saw thought as a subjective primitive out of which knowledge was composed, Dewey's approach understood thought genetically, as the product of the interaction between organism and environment, and knowledge as having practical instrumentality in the guidance and control of that interaction. Thus Dewey adopted the term "instrumentalism" as a descriptive appellation for his new approach.

Dewey's first significant application of this new naturalistic understanding was offered in his seminal article "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" (1896). In this article, Dewey argued that the dominant conception of the reflex arc in the psychology of his day, which was thought to begin with the passive stimulation of the organism, causing a conscious act of awareness eventuating in a response, was a carry-over of the old, and errant, mind-body dualism. Dewey argued for an alternative view: the organism interacts with the world through self-guided activity that coordinates and integrates sensory and motor responses. The implication for the theory of knowledge was clear: the world is not passively perceived and thereby known; active manipulation of the environment is involved integrally in the process of learning from the start.

Dewey first applied this interactive naturalism in an explicit manner to the theory of knowledge in his four introductory essays in Studies in Logical Theory. Dewey identified the view expressed in Studies with the school of pragmatism, crediting William James as its progenitor. James, for his part, in an article appearing in the Psychological Bulletin, proclaimed the work as the expression of a new school of thought, acknowledging its originality.

A detailed genetic analysis of the process of inquiry was Dewey's signal contribution to Studies. Dewey distinguished three phases of the process. It begins with the problematic situation, a situation where instinctive or habitual responses of the human organism to the environment are inadequate for the continuation of ongoing activity in pursuit of the fulfillment of needs and desires. Dewey stressed inStudies and subsequent writings that the uncertainty of the problematic situation is not inherently cognitive, but practical and existential. Cognitive elements enter into the process as a response to precognitive maladjustment.

The second phase of the process involves the isolation of the data or subject matter which defines the parameters within which the reconstruction of the initiating situation must be addressed. In the third, reflective phase of the process, the cognitive elements of inquiry (ideas, suppositions, theories, etc.) are entertained as hypothetical solutions to the originating impediment of the problematic situation, the implications of which are pursued in the abstract. The final test of the adequacy of these solutions comes with their employment in action. If a reconstruction of the antecedent situation conducive to fluid activity is achieved, then the solution no longer retains the character of the hypothetical that marks cognitive thought; rather, it becomes a part of the existential circumstances of human life.

The error of modern epistemologists, as Dewey saw it, was that they isolated the reflective stages of this process, and hypostatized the elements of those stages (sensations, ideas, etc.) into pre-existing constituents of a subjective mind in their search for an incorrigible foundation of knowledge. For Dewey, the hypostatization was as groundless as the search for incorrigibility was barren. Rejecting foundationalism, Dewey accepted the fallibilism that was characteristic of the school of pragmatism: the view that any proposition accepted as an item of knowledge has this status only provisionally, contingent upon its adequacy in providing a coherent understanding of the world as the basis for human action.

Dewey defended this general outline of the process of inquiry throughout his long career, insisting that it was the only proper way to understand the means by which we attain knowledge, whether it be the commonsense knowledge that guides the ordinary affairs of our lives, or the sophisticated knowledge arising from scientific inquiry. The latter is only distinguished from the former by the precision of its methods for controlling data, and the refinement of its hypotheses. In his writings in the theory of inquiry subsequent to Studies, Dewey endeavored to develop and deepen instrumentalism by considering a number of central issues of traditional epistemology from its perspective, and responding to some of the more trenchant criticisms of the view.

One traditional question that Dewey addressed in a series of essays between 1906 and 1909 was that of the meaning of truth. Dewey at that time considered the pragmatic theory of truth as central to the pragmatic school of thought, and vigorously defended its viability. Both Dewey and William James, in his book Pragmatism (1907), argued that the traditional correspondence theory of truth, according to which the true idea is one that agrees or corresponds to reality, only begs the question of what the "agreement" or "correspondence" of idea with reality is. Dewey and James maintained that an idea agrees with reality, and is therefore true, if and only if it is successfully employed in human action in pursuit of human goals and interests, that is, if it leads to the resolution of a problematic situation in Dewey's terms. The pragmatic theory of truth met with strong opposition among its critics, perhaps most notably from the British logician and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Dewey later began to suspect that the issues surrounding the conditions of truth, as well as knowledge, were hopelessly obscured by the accretion of traditional, and in his view misguided, meanings to the terms, resulting in confusing ambiguity. He later abandoned these terms in favor of "warranted assertiblity" to describe the distinctive property of ideas that results from successful inquiry.

One of the most important developments of his later writings in the theory of knowledge was the application of the principles of instrumentalism to the traditional conceptions and formal apparatus of logical theory. Dewey made significant headway in this endeavor in his lengthy introduction to Essays in Experimental Logic, but the project reached full fruition in Logic: The Theory of Inquiry.

The basis of Dewey's discussion in the Logic is the continuity of intelligent inquiry with the adaptive responses of pre-human organisms to their environments in circumstances that check efficient activity in the fulfillment of organic needs. What is distinctive about intelligent inquiry is that it is facilitated by the use of language, which allows, by its symbolic meanings and implication relationships, the hypothetical rehearsal of adaptive behaviors before their employment under actual, prevailing conditions for the purpose of resolving problematic situations. Logical form, the specialized subject matter of traditional logic, owes its genesis not to rational intuition, as had often been assumed by logicians, but due to its functional value in (1) managing factual evidence pertaining to the problematic situation that elicits inquiry, and (2) controlling the procedures involved in the conceptualized entertainment of hypothetical solutions. As Dewey puts it, "logical forms accrue to subject-matter when the latter is subjected to controlled inquiry."

From this new perspective, Dewey reconsiders many of the topics of traditional logic, such as the distinction between deductive and inductive inference, propositional form, and the nature of logical necessity. One important outcome of this work was a new theory of propositions. Traditional views in logic had held that the logical import of propositions is defined wholly by their syntactical form (e.g., "All As are Bs," "Some Bs are Cs"). In contrast, Dewey maintained that statements of identical propositional form can play significantly different functional roles in the process of inquiry. Thus in keeping with his distinction between the factual and conceptual elements of inquiry, he replaced the accepted distinctions between universal, particular, and singular propositions based on syntactical meaning with a distinction between existential and ideational propositions, a distinction that largely cuts across traditional classifications. The same general approach is taken throughout the work: the aim is to offer functional analyses of logical principles and techniques that exhibit their operative utility in the process of inquiry as Dewey understood it.

The breadth of topics treated and the depth and continuity of the discussion of these topics mark theLogic as Dewey's decisive statement in logical theory. The recognition of the work's importance within the philosophical community of the time can be gauged by the fact that the Journal of Philosophy, the most prominent American journal in the field, dedicated an entire issue to a discussion of the work, including contributions by such philosophical luminaries as C. I. Lewis of Harvard University, and Ernest Nagel, Dewey's colleague at Columbia University. Although many of his critics did question, and continue to question, the assumptions of his approach, one that is certainly unique in the development of twentieth century logical theory, there is no doubt that the work was and continues to be an important contribution to the field.

3. Metaphysics

Dewey's naturalistic metaphysics first took shape in articles that he wrote during the decade after the publication of Studies in Logical Theory, a period when he was attempting to elucidate the implications of instrumentalism. Dewey disagreed with William James's assessment that pragmatic principles were metaphysically neutral. (He discusses this disagreement in "What Does Pragmatism Mean by Practical," published in 1908.) Dewey's view was based in part on an assessment of the motivations behind traditional metaphysics: a central aim of the metaphysical tradition had been the discovery of an immutable cognitive object that could serve as a foundation for knowledge. The pragmatic theory, by showing that knowledge is a product of an activity directed to the fulfillment of human purposes, and that a true (or warranted) belief is known to be such by the consequences of its employment rather than by any psychological or ontological foundations, rendered this longstanding aim of metaphysics, in Dewey's view, moot, and opened the door to renewed metaphysical discussion grounded firmly on an empirical basis.

Dewey begins to define the general form that an empirical metaphysics should take in a number of articles, including "The Postulate of Immediate Empiricism" (1905) and "Does Reality Possess Practical Character?" (1908). In the former article, Dewey asserts that things experienced empirically "are what they are experienced as." Dewey uses as an example a noise heard in a darkened room that is initially experienced as fearsome. Subsequent inquiry (e.g., turning on the lights and looking about) reveals that the noise was caused by a shade tapping against a window, and thus innocuous. But the subsequent inquiry, Dewey argues, does not change the initial status of the noise: it was experienced as fearsome, and in fact was fearsome. The point stems from the naturalistic roots of Dewey's logic. Our experience of the world is constituted by our interrelationship with it, a relationship that is imbued with practical import. The initial fearsomeness of the noise is the experiential correlate of the uncertain, problematic character of the situation, an uncertainty that is not merely subjective or mental, but a product of the potential inadequacy of previously established modes of behavior to deal effectively with the pragmatic demands of present circumstances. The subsequent inquiry does not, therefore, uncover a reality (the innocuousness of the noise) underlying a mere appearance (its fearsomeness), but by settling the demands of the situation, it effects a change in the inter-dynamics of the organism-environment relationship of the initial situation--a change in reality.

There are two important implications of this line of thought that distinguish it from the metaphysical tradition. First, although inquiry is aimed at resolving the precarious and confusing aspects of experience to provide a stable basis for action, this does not imply the unreality of the unstable and contingent, nor justify its relegation to the status of mere appearance. Thus, for example, the usefulness and reliability of utilizing certain stable features of things encountered in our experience as a basis for classification does not justify according ultimate reality to essences or Platonic forms any more than, as rationalist metaphysicians in the modern era have thought, the similar usefulness of mathematical reasoning in understanding natural processes justifies the conclusion that the world can be exhaustively defined mathematically.

Second, the fact that the meanings we attribute to natural events might change in any particular in the future as renewed inquiries lead to more adequate understandings of natural events (as was implied by Dewey's fallibilism) does not entail that our experience of the world at any given time may as a whole be errant. Thus the implicit skepticism that underlies the representational theory of ideas and raises questions concerning the veracity of perceptual experience as such is unwarranted. Dewey stresses the point that sensations, hypotheses, ideas, etc., come into play to mediate our encounter with the world only in the context of active inquiry. Once inquiry is successful in resolving a problematic situation, mediatory sensations and ideas, as Dewey says, "drop out; and things are present to the agent in the most naively realistic fashion."

These contentions positioned Dewey's metaphysics within the territory of a naive realism, and in a number of his articles, such as "The Realism of Pragmatism" (1905), "Brief Studies in Realism" (1911), and "The Existence of the World as a Logical Problem" (1915), it is this view that Dewey expressly avows (a view that he carefully distinguishes from what he calls "presentational realism," which he attributes to a number of the other realists of his day). Opposing narrow-minded positions that would accord full ontological status only to certain, typically the most stable or reliable, aspects of experience, Dewey argues for a position that recognizes the real significance of the multifarious richness of human experience.

Dewey offered a fuller statement of his metaphysics in 1925, with the publication of one of his most significant philosophical works, Experience and Nature. In the introductory chapter, Dewey stresses a familiar theme from his earlier writings: that previous metaphysicians, guided by unavowed biases for those aspects of experience that are relatively stable and secure, have illicitly reified these biases into narrow ontological presumptions, such as the temporal identity of substance, or the ultimate reality of forms or essences. Dewey finds this procedure so pervasive in the history of thought that he calls it simplythe philosophic fallacy, and signals his intention to eschew the disastrous consequences of this approach by offering a descriptive account of all of the various generic features of human experience, whatever their character.

Dewey begins with the observation that the world as we experience it both individually and collectively is an admixture of the precarious, the transitory and contingent aspect of things, and the stable, the patterned regularity of natural processes that allows for prediction and human intervention. Honest metaphysical description must take into account both of these elements of experience. Dewey endeavors to do this by an event ontology. The world, rather than being comprised of things or, in more traditional terms, substances, is comprised of happenings or occurrences that admit of both episodic uniqueness and general, structured order. Intrinsically events have an ineffable qualitative character by which they are immediately enjoyed or suffered, thus providing the basis for experienced value and aesthetic appreciation. Extrinsically events are connected to one another by patterns of change and development; any given event arises out of determinant prior conditions and leads to probable consequences. The patterns of these temporal processes is the proper subject matter of human knowledge--we know the world in terms of causal laws and mathematical relationships--but the instrumental value of understanding and controlling them should not blind us to the immediate, qualitative aspect of events; indeed, the value of scientific understanding is most significantly realized in the facility it affords for controlling the circumstances under which immediate enjoyments may be realized.

It is in terms of the distinction between qualitative immediacy and the structured order of events that Dewey understands the general pattern of human life and action. This understanding is captured by James' suggestive metaphor that human experience consists of an alternation of flights and perchings, an alternation of concentrated effort directed toward the achievement of foreseen aims, what Dewey calls "ends-in-view," with the fruition of effort in the immediate satisfaction of "consummatory experience." Dewey's insistence that human life follows the patterns of nature, as a part of nature, is the core tenet of his naturalistic outlook.

Dewey also addresses the social aspect of human experience facilitated by symbolic activity, particularly that of language. For Dewey the question of the nature of social relationships is a significant matter not only for social theory, but metaphysics as well, for it is from collective human activity, and specifically the development of shared meanings that govern this activity, that the mind arises. Thus rather than understanding the mind as a primitive and individual human endowment, and a precondition of conscious and intentional action, as was typical in the philosophical tradition since Descartes, Dewey offers a genetic analysis of mind as an emerging aspect of cooperative activity mediated by linguistic communication. Consciousness, in turn, is not to be understood as a domain of private awareness, but rather as the fulcrum point of the organism's readjustment to the challenge of novel conditions where the meanings and attitudes that formulate habitual behavioral responses to the environment fail to be adequate. Thus Dewey offers in the better part of a number of chapters of Experience and Nature a response to the traditional mind-body problem of the metaphysical tradition, a response that understands the mind as an emergent issue of natural processes, more particularly the web of interactive relationships between human beings and the world in which they live.

4. Ethical and Social Theory

Dewey's mature thought in ethics and social theory is not only intimately linked to the theory of knowledge in its founding conceptual framework and naturalistic standpoint, but also complementary to it in its emphasis on the social dimension of inquiry both in its processes and its consequences. In fact, it would be reasonable to claim that Dewey's theory of inquiry cannot be fully understood either in the meaning of its central tenets or the significance of its originality without considering how it applies to social aims and values, the central concern of his ethical and social theory.

Dewey rejected the atomistic understanding of society of the Hobbesian social contract theory, according to which the social, cooperative aspect of human life was grounded in the logically prior and fully articulated rational interests of individuals. Dewey's claim in Experience and Nature that the collection of meanings that constitute the mind have a social origin expresses the basic contention, one that he maintained throughout his career, that the human individual is a social being from the start, and that individual satisfaction and achievement can be realized only within the context of social habits and institutions that promote it.

Moral and social problems, for Dewey, are concerned with the guidance of human action to the achievement of socially defined ends that are productive of a satisfying life for individuals within the social context. Regarding the nature of what constitutes a satisfying life, Dewey was intentionally vague, out of his conviction that specific ends or goods can be defined only in particular socio-historical contexts. In theEthics (1932) he speaks of the ends simply as the cultivation of interests in goods that recommend themselves in the light of calm reflection. In other works, such as Human Nature and Conduct and Art as Experience, he speaks of (1) the harmonizing of experience (the resolution of conflicts of habit and interest both within the individual and within society), (2) the release from tedium in favor of the enjoyment of variety and creative action, and (3) the expansion of meaning (the enrichment of the individual's appreciation of his or her circumstances within human culture and the world at large). The attunement of individual efforts to the promotion of these social ends constitutes, for Dewey, the central issue of ethical concern of the individual; the collective means for their realization is the paramount question of political policy.

Conceived in this manner, the appropriate method for solving moral and social questions is the same as that required for solving questions concerning matters of fact: an empirical method that is tied to an examination of problematic situations, the gathering of relevant facts, and the imaginative consideration of possible solutions that, when utilized, bring about a reconstruction and resolution of the original situations. Dewey, throughout his ethical and social writings, stressed the need for an open-ended, flexible, and experimental approach to problems of practice aimed at the determination of the conditions for the attainment of human goods and a critical examination of the consequences of means adopted to promote them, an approach that he called the "method of intelligence."

The central focus of Dewey's criticism of the tradition of ethical thought is its tendency to seek solutions to moral and social problems in dogmatic principles and simplistic criteria which in his view were incapable of dealing effectively with the changing requirements of human events. In Reconstruction of Philosophyand The Quest for Certainty, Dewey located the motivation of traditional dogmatic approaches in philosophy in the forlorn hope for security in an uncertain world, forlorn because the conservatism of these approaches has the effect of inhibiting the intelligent adaptation of human practice to the ineluctable changes in the physical and social environment. Ideals and values must be evaluated with respect to their social consequences, either as inhibitors or as valuable instruments for social progress, and Dewey argues that philosophy, because of the breadth of its concern and its critical approach, can play a crucial role in this evaluation.

In large part, then, Dewey's ideas in ethics and social theory were programmatic rather than substantive, defining the direction that he believed human thought and action must take in order to identify the conditions that promote the human good in its fullest sense, rather than specifying particular formulae or principles for individual and social action. He studiously avoided participating in what he regarded as the unfortunate practice of previous moral philosophers of offering general rules that legislate universal standards of conduct. But there are strong suggestions in a number of his works of basic ethical and social positions. In Human Nature and Conduct Dewey approaches ethical inquiry through an analysis of human character informed by the principles of scientific psychology. The analysis is reminiscent of Aristotelian ethics, concentrating on the central role of habit in formulating the dispositions of action that comprise character, and the importance of reflective intelligence as a means of modifying habits and controlling disruptive desires and impulses in the pursuit of worthwhile ends.

The social condition for the flexible adaptation that Dewey believed was crucial for human advancement is a democratic form of life, not instituted merely by democratic forms of governance, but by the inculcation of democratic habits of cooperation and public spiritedness, productive of an organized, self-conscious community of individuals responding to society's needs by experimental and inventive, rather than dogmatic, means. The development of these democratic habits, Dewey argues in School and Society andDemocracy and Education, must begin in the earliest years of a child's educational experience. Dewey rejected the notion that a child's education should be viewed as merely a preparation for civil life, during which disjoint facts and ideas are conveyed by the teacher and memorized by the student only to be utilized later on. The school should rather be viewed as an extension of civil society and continuous with it, and the student encouraged to operate as a member of a community, actively pursuing interests in cooperation with others. It is by a process of self-directed learning, guided by the cultural resources provided by teachers, that Dewey believed a child is best prepared for the demands of responsible membership within the democratic community.

5. Aesthetics

Dewey's one significant treatment of aesthetic theory is offered in Art as Experience, a book that was based on the William James Lectures that he delivered at Harvard University in 1931. The book stands out as a diversion into uncommon philosophical territory for Dewey, adumbrated only by a somewhat sketchy and tangential treatment of art in one chapter of Experience and Nature. The unique status of the work in Dewey's corpus evoked some criticism from Dewey's followers, most notably Stephen Pepper, who believed that it marked an unfortunate departure from the naturalistic standpoint of his instrumentalism, and a return to the idealistic viewpoints of his youth. On close reading, however, Art as Experience reveals a considerable continuity of Dewey's views on art with the main themes of his previous philosophical work, while offering an important and useful extension of those themes. Dewey had always stressed the importance of recognizing the significance and integrity of all aspects of human experience. His repeated complaint against the partiality and bias of the philosophical tradition expresses this theme. Consistent with this theme, Dewey took account of qualitative immediacy in Experience and Nature, and incorporated it into his view of the developmental nature of experience, for it is in the enjoyment of the immediacy of an integration and harmonization of meanings, in the "consummatory phase" of experience that, in Dewey's view, the fruition of the re-adaptation of the individual with environment is realized. These central themes are enriched and deepened in Art as Experience, making it one of Dewey's most significant works.

The roots of aesthetic experience lie, Dewey argues, in commonplace experience, in the consummatory experiences that are ubiquitous in the course of human life. There is no legitimacy to the conceit cherished by some art enthusiasts that aesthetic enjoyment is the privileged endowment of the few. Whenever there is a coalesence into an immediately enjoyed qualitative unity of meanings and values drawn from previous experience and present circumstances, life then takes on an aesthetic quality--what Dewey called having "an experience." Nor is the creative work of the artist, in its broad parameters, unique. The process of intelligent use of materials and the imaginative development of possible solutions to problems issuing in a reconstruction of experience that affords immediate satisfaction, the process found in the creative work of artists, is also to be found in all intelligent and creative human activity. What distinguishes artistic creation is the relative stress laid upon the immediate enjoyment of unified qualitative complexity as the rationalizing aim of the activity itself, and the ability of the artist to achieve this aim by marshalling and refining the massive resources of human life, meanings, and values.

The senses play a key role in artistic creation and aesthetic appreciation. Dewey, however, argues against the view, stemming historically from the sensationalistic empiricism of David Hume, that interprets the content of sense experience simply in terms of the traditionally codified list of sense qualities, such as color, odor, texture, etc., divorced from the funded meanings of past experience. It is not only the sensible qualities present in the physical media the artist uses, but the wealth of meaning that attaches to these qualities, that constitute the material that is refined and unified in the process of artistic expression. The artist concentrates, clarifies, and vivifies these meanings in the artwork. The unifying element in this process is emotion--not the emotion of raw passion and outburst, but emotion that is reflected upon and used as a guide to the overall character of the artwork. Although Dewey insisted that emotion is not the significant content of the work of art, he clearly understands it to be the crucial tool of the artist's creative activity.

Dewey repeatedly returns in Art as Experience to a familiar theme of his critical reflections upon the history of ideas, namely that a distinction too strongly drawn too often sacrifices accuracy of account for a misguided simplicity. Two applications of this theme are worth mentioning here. Dewey rejects the sharp distinction often made in aesthetics between the matter and the form of an artwork. What Dewey objected to was the implicit suggestion that matter and form stand side by side, as it were, in the artwork as distinct and precisely distinguishable elements. For Dewey, form is better understood in a dynamic sense as the coordination and adjustment of the qualities and associated meanings that are integrated within the artwork.

A second misguided distinction that Dewey rejects is that between the artist as the active creator and the audience as the passive recipient of art. This distinction artificially truncates the artistic process by in effect suggesting that the process ends with the final artifact of the artist's creativity. Dewey argues that, to the contrary, the process is barren without the agency of the appreciator, whose active assimilation of the artist's work requires a recapitulation of many of the same processes of discrimination, comparison, and integration that are present in the artist's initial work, but now guided by the artist's perception and skill. Dewey underscores the point by distinguishing between the "art product," the painting, sculpture, etc., created by the artist, and the "work of art" proper, which is only realized through the active engagement of an astute audience.

Ever concerned with the interrelationships between the various domains of human activity and concern, Dewey ends Art as Experience with a chapter devoted to the social implications of the arts. Art is a product of culture, and it is through art that the people of a given culture express the significance of their lives, as well as their hopes and ideals. Because art has its roots in the consummatory values experienced in the course of human life, its values have an affinity to commonplace values, an affinity that accords to art a critical office in relation to prevailing social conditions. Insofar as the possibility for a meaningful and satisfying life disclosed in the values embodied in art is not realized in the lives of the members of a society, the social relationships that preclude this realization are condemned. Dewey's specific target in this chapter was the conditions of workers in industrialized society, conditions which force upon the worker the performance of repetitive tasks that are devoid of personal interest and afford no satisfaction in personal accomplishment. The degree to which this critical function of art is ignored is a further indication of what Dewey regarded as the unfortunate distancing of the arts from the common pursuits and interests of ordinary life. The realization of art's social function requires the closure of this bifurcation.

6. Critical Reception and Influence

Dewey's philosophical work received varied responses from his philosophical colleagues during his lifetime. There were many philosophers who saw his work, as Dewey himself understood it, as a genuine attempt to apply the principles of an empirical naturalism to the perennial questions of philosophy, providing a beneficial clarification of issues and the concepts used to address them. Dewey's critics, however, often expressed the opinion that his views were more confusing than clarifying, and that they appeared to be more akin to idealism than the scientifically based naturalism Dewey expressly avowed. Notable in this connection are Dewey's disputes concerning the relation of the knowing subject to known objects with the realists Bertrand Russell, A. O. Lovejoy, and Evander Bradley McGilvery. Whereas these philosophers argued that the object of knowledge must be understood as existing apart from the knowing subject, setting the truth conditions for propositions, Dewey defended the view that things understood as isolated from any relationship with the human organism could not be objects of knowledge at all.

Dewey was sensitive and responsive to the criticisms brought against his views. He often attributed them to misinterpretations based on the traditional, philosophical connotations that some of his readers would attach to his terminology. This was clearly a fair assessment with respect to some of his critics. To take one example, Dewey used the term "experience," found throughout his philosophical writings, to denote the broad context of the human organism's interrelationship with its environment, not the domain of human thought alone, as some of his critics read him to mean. Dewey's concern for clarity of expression motivated efforts in his later writings to revise his terminology. Thus, for example, he later substituted "transaction" for his earlier "interaction" to denote the relationship between organism and environment, since the former better suggested a dynamic interdependence between the two, and in a new introduction to Experience and Nature, never published during his lifetime, he offered the term "culture" as an alternative to "experience." Late in his career he attempted a more sweeping revision of philosophical terminology in Knowing and the Known, written in collaboration with Arthur F. Bentley.

The influence of Dewey's work, along with that of the pragmatic school of thought itself, although considerable in the first few decades of the twentieth century, was gradually eclipsed during the middle part of the century as other philosophical methods, such as those of the analytic school in England and America and phenomenology in continental Europe, grew to ascendency. Recent trends in philosophy, however, leading to the dissolution of these rigid paradigms, have led to approaches that continue and expand on the themes of Dewey's work. W. V. O. Quine's project of naturalizing epistemology works upon naturalistic presumptions anticipated in Dewey's own naturalistic theory of inquiry. The social dimension and function of belief systems, explored by Dewey and other pragmatists, has received renewed attention by such writers as Richard Rorty and Jürgen Habermas. American phenomenologists such as Sandra Rosenthal and James Edie have considered the affinities of phenomenology and pragmatism, and Hilary Putnam, an analytically trained philosophy, has recently acknowledged the affinity of his own approach to ethics to that of Dewey's. The renewed openness and pluralism of recent philosophical discussion has meant a renewed interest in Dewey's philosophy, an interest that promises to continue for some time to come.

7. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

All of the published writings of John Dewey have been newly edited and published in The Collected Works of John Dewey, Jo Ann Boydston, ed., 37 volumes (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967-1991).

Dewey's complete correspondence has know been published in electronic form in The Correspondence of John Dewey, 3 vols., Larry Hickman, ed. (Charlottesville, Va: Intelex Corporation).

An authoritative collection of Dewey's writings is The Essential Dewey, 2 vols., Larry Hickman and Thomas M. Alexander, eds. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998).

b. Secondary Sources

- Alexander, Thomas M. The Horizons of Feeling: John Dewey's Theory of Art, Experience, and Nature. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987.

- Boisvert, Raymond D. Dewey's Metaphysics. New York: Fordham University Press, 1988.

- Boisvert, Raymond D. John Dewey: Rethinking Our Time. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

- Bullert, Gary. The Politics of John Dewey. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1983.

- Campbell, James. Understanding John Dewey: Nature and Cooperative Intelligence. Chicago and La Salle: Open Court, 1995.

- Damico, Alfonso J. Individuality and Community: The Social and Political Thought of John Dewey. Gainesville, FL: University Presses of Florida, 1978.

- Dykhuizen, George. The Life and Mind of John Dewey. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973.

- Eames, S. Morris. Experience and Value: Essays on John Dewey and Pragmatic Naturalism.Elizabeth R. Eames and Richard W. Field, eds. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

- Eldridge, Michael. Transforming Experience: John Dewey's Cultural Instrumentalism. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1998.

- Gouinlock, James. John Dewey's Philosophy of Value. New York: Humanities Press, 1972.

- Hickman, Larry. John Dewey's Pragmatic Technology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

- Hickman, Larry A., ed. Reading Dewey: Interpretations for a Postmodern Generation. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998.

- Hook, Sidney. John Dewey: An Intellectual Portrait. New York: John Day Co., 1939; New York: Prometheus Books, 1995.

- Jackson, Philip W. John Dewey and the Lessons of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Haskins, Casey and David I. Seiple, eds. Dewey Reconfigured: Essays on Deweyan Pragmatism.Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999.

- Levine, Barbara. Works about John Dewey: 1886-1995. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996.

- Rockefeller, Steven C. John Dewey: Religious Faith and Democratic Humanism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

- Schilpp, Paul Arthur and Lewis Edwin Hahn, eds. The Philosophy of John Dewey, The Library of Living Philosophers, vol. 1. La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1989.

- Sleeper, Ralph. The Necessity of Pragmatism: John Dewey's Conception of Philosophy. New York: Yale University Press, 1987.

- Thayer, H. S. The Logic of Pragmatism: An Examination of John Dewey's Logic. New York: Humanities Press, 1952.

- Tiles, J. E. Dewey. London: Routledge, 1988.

- Welchman, Jennifer. Dewey's Ethical Thought. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995.