About Sigmund Freud

April 5, 2017Psychoanalysis

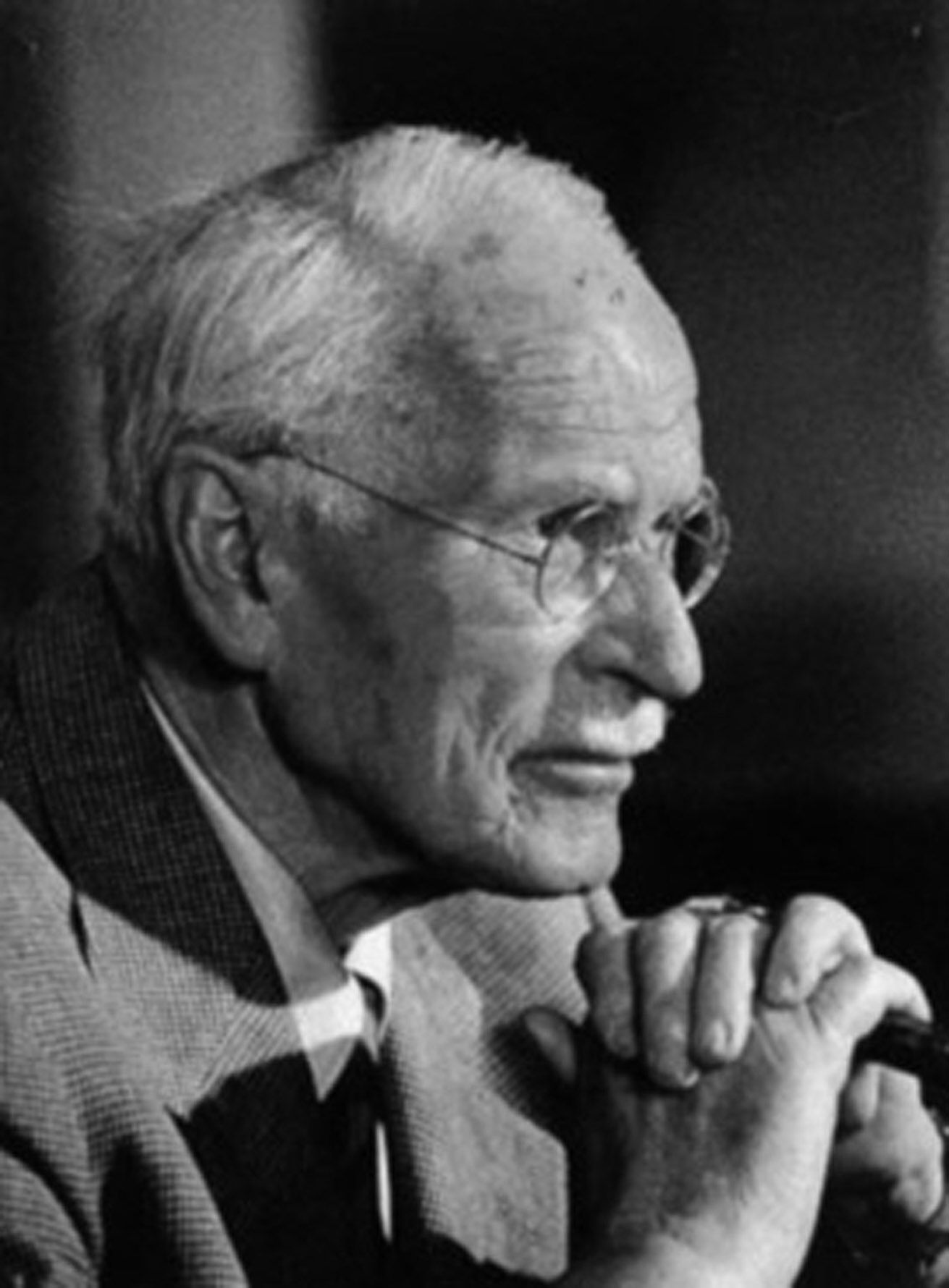

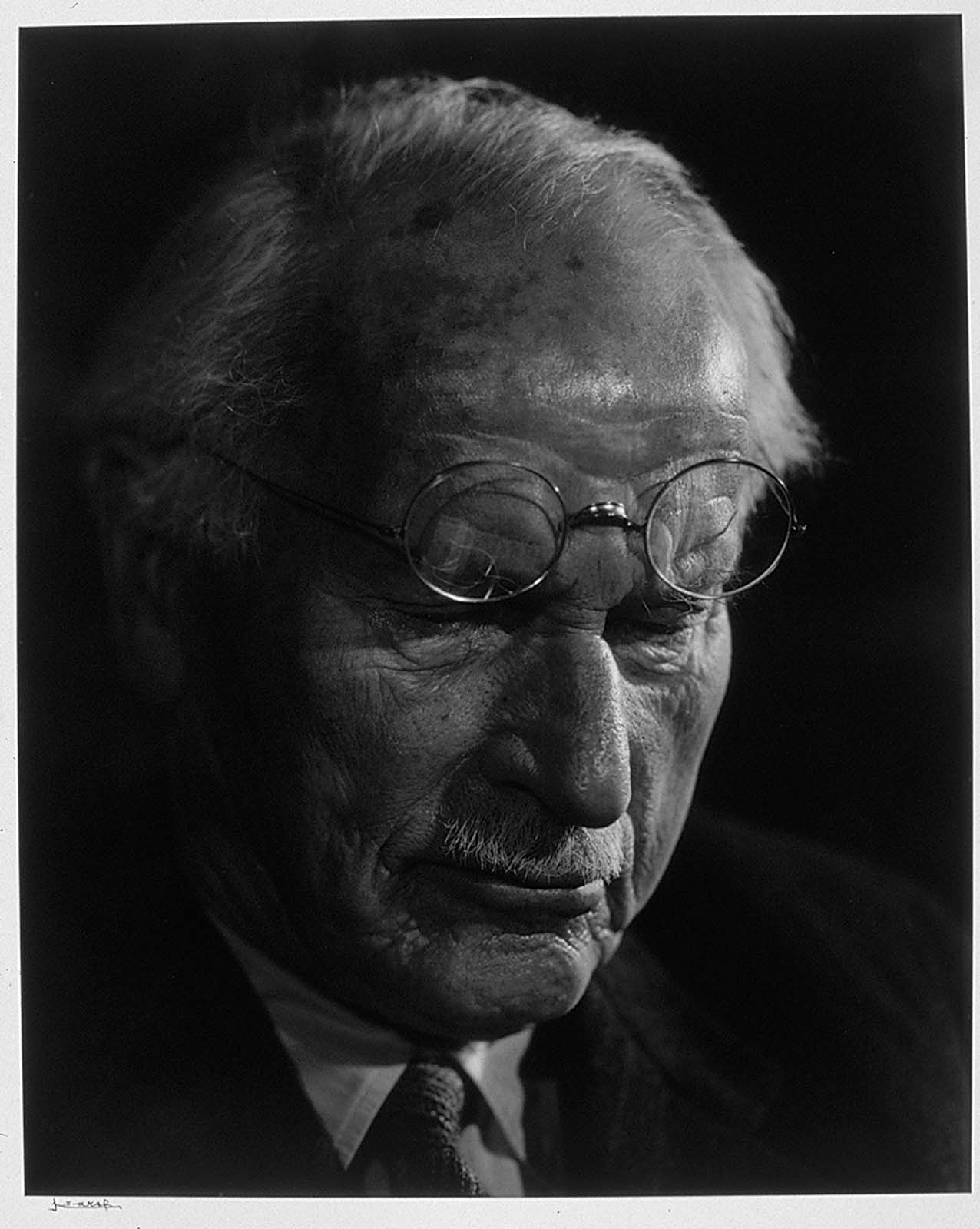

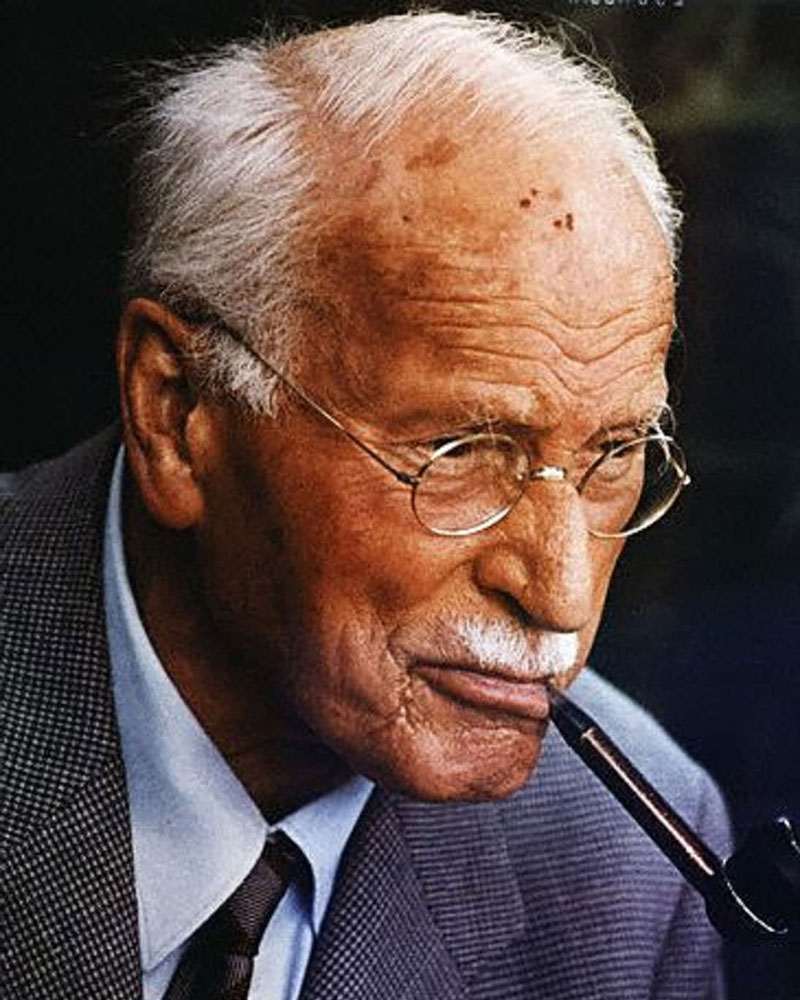

About Carl Gustav Jung

C arl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), founder of analytical psychology, was born the son of a clergyman in Kesswil (Thurgau canton, Switzerland) on Lake Constance. At the age of four he went to Basel, which he regarded as his hometown: his mother was born there, and he went to school and received his doctorate in medicine there. Several of his ancestors on his mother’s side were also Protestant theologians, including his grandfather and greatgrandfather. His paternal great-grandfather, however, was a Roman Catholic Kirchenrat (member of a consistory) in Mainz, and his grandfather was in his eighteenth year when he was converted by Schleiermacher to Protestantism. This heritage of concern with religious problems may have been the source of the questioning always characteristic of his work. Despite an inclination toward the humanities, his ancestors on his father’s side also included physicians who exercised an enduring influence on Jung’s intellectual development. His paternal grandfather, an aesthete and poet, was exiled from Germany for his revolutionary views; he was called to the chair of surgery in the University of Basel in 1822 through the intercession of Alexander von Humboldt and later founded the first insane asylum there, as well as the Ansta’t zur Hoffnung, a home for mentally retarded children.

Early career in psychiatry

As a young man, Jung was full of enthusiasm for biology, zoology, and paleontology; it was only later that he shifted to medicine. At the same time, philosophy and the history of religion excited him, and the list of great men who had a decisive influence upon him is a long one; it includes Heraclitus, Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, Paracelsus, Bohme, Joachim of Floris, Goethe, Carus, Hölderlin, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Freud, to name but a few. From as early as 1898 until the end of his life, occultism and mysticism interested him, as did the study of mythology. Thus, his lifework has that significant double aspect that ties it, on the one hand, to the natural sciences and, on the other, to the humanities. As he saw it, this was the only way to do justice to the multilayered structure of the psyche.

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), founder of analytical psychology, was born the son of a clergyman in Kesswil (Thurgau canton, Switzerland) on Lake Constance. At the age of four he went to Basel, which he regarded as his hometown: his mother was born there, and he went to school and received his doctorate in medicine there. Several of his ancestors on his mother’s side were also Protestant theologians, including his grandfather and greatgrandfather. His paternal great-grandfather, however, was a Roman Catholic Kirchenrat (member of a consistory) in Mainz, and his grandfather was in his eighteenth year when he was converted by Schleiermacher to Protestantism. This heritage of concern with religious problems may have been the source of the questioning always characteristic of his work. Despite an inclination toward the humanities, his ancestors on his father’s side also included physicians who exercised an enduring influence on Jung’s intellectual development. His paternal grandfather, an aesthete and poet, was exiled from Germany for his revolutionary views; he was called to the chair of surgery in the University of Basel in 1822 through the intercession of Alexander von Humboldt and later founded the first insane asylum there, as well as the Ansta’t zur Hoffnung, a home for mentally retarded children.

As a young man, Jung was full of enthusiasm for biology, zoology, and paleontology; it was only later that he shifted to medicine. At the same time, philosophy and the history of religion excited him, and the list of great men who had a decisive influence upon him is a long one; it includes Heraclitus, Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, Paracelsus, Bohme, Joachim of Floris, Goethe, Carus, Hölderlin, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Freud, to name but a few. From as early as 1898 until the end of his life, occultism and mysticism interested him, as did the study of mythology. Thus, his lifework has that significant double aspect that ties it, on the one hand, to the natural sciences and, on the other, to the humanities. As he saw it, this was the only way to do justice to the multilayered structure of the psyche.

Early career in psychiatry

Jung began as an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at Burghölzli, the psychiatric clinic of the University of Zurich. In 1902 the degree of doctor of medicine was conferred upon him for his dissertation, “On the Psychology and Pathology of Socalled Occult Phenomena” (1902). His later fundamental notion that there is in every individual a natural predisposition toward a “totality of the psyche” is first set forth here. He left for Paris that same year, studying with Pierre Janet for a semester, and then went to London to broaden his knowledge of psychopathology. In 1903 he married Emma Rauschenbach of Schaffhausen, who was his loyal companion and scientific collaborator until her death in 1955. With her he moved to their permanent home situated in a large garden in Kiisnacht on the shore of Lake Zurich, where he lived until his death.

Around the time of his marriage, Jung, together with a few associates, began his systematic investigations at the Burghölzli, the first fruits of which were his publication of Studies in Wordassociation in 1904 and 1909. The method of testing that he elaborated in these studies was used to reveal affectively significant groups of ideas in the unconscious region of the psyche. To designate them, he coined the term “complexes,” which has since become part of our everyday language. The association test made him known throughout the world (it won him, among other things, an honorary degree conferred by Clark University in the United States). Today it is still part of the diagnostic equipment of mental hospitals and courts, and it is used for training in personality diagnosis and for vocational guidance of all kinds. It likewise provided the initial impetus for his closer acquaintance in 1907 with Sigmund Freud, in whose work on the interpretation of dreams Jung found his own ideas and observations to be essentially confirmed and furthered.

Jung is generally regarded as a disciple, and an unfaithful one, of Freud. This is not at all correct. Jung did accept Freud’s findings and methods in the years of their close association, but the decisive underlying concept of Jung’s work may be traced back to the very beginnings of his career, many years before he met Freud. Today we know that the role of a lifelong disciple was inconceivable for Jung; his own stature would soon have broken such bonds. Thus it was that their collaboration could last but a short time; nevertheless, it did last from 1907 to 1913. After a joint lecture tour through the United States in 1909 and four years (1909–1913) as an editor of the Bleuler–Freud Jahrbuch fur psychologische und psychopathologische Forschungen and as the president of the International Psychoanalytic Society, which he himself founded, Jung’s path branched off in a different direction. This was foreshadowed as early as 1912 in his book Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (Symbols of Transformation, 1902–1959, vol. 5), in which he sought to elaborate the symbolic meaning of the dreams and fantasies of a young woman by the use of mythological parallels. With this book Jung advanced to a new position. He was unable to accept many of Freud’s most essential doctrines, such as the theory of wish fulfillment and the theory of infantile sexuality. To distinguish his own doctrine from Freud’s “psychoanalysis” and Adler’s “individual psychology,” he thenceforth called his theory “analytical psychology.” Later he himself called its theoretical aspect “complex psychology,” because of the complexity of its subject, but today only the earlier designation is employed.

Jung’s radically different approach was based in the last analysis on a Weltanschauung that differed from Freud’s. Freud’s positions remained grounded in the theories of cognition of the nineteenth century, while Jung’s were linked with that of the twentieth, which has brought with it revolutionary innovations in so many branches of science, especially modern physics and depth psychology.

After publishing numerous studies on psychiatric problems, among which his paper “The Psychology of Dementia Praecox” (1907) and several other of his articles anticipate modern interpretations of schizophrenia, Jung gave up his work at Burgholzli in 1909 and in 1913 resigned his lectureship at the University of Zurich, which he had held since 1905, to devote himself entirely to his private medical and psychotherapeutic practice, scientific research, writing, and travel.

Travels and spiritual explorations

In 1912–1913 Jung traveled repeatedly to France, Italy, and the United States; his travels ended with World War I. In addition to his military duties, Jung entered upon a period of intensive soulsearching and strenuous empirical scientific endeavor. Then there followed other voyages of discovery to study the psychology of primitive peoples by direct contact with them. In 1920 Jung was in Tunis and Algiers, in 1924–1925 among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico and Arizona, in 1925–1926 among the inhabitants of Mount Elgon in Kenya, and later in Egypt. He was aiming, in particular, to uncover the analogies between the unconscious psychic contents of modern Western man and certain manifestations of the psyche in primitive peoples, as well as of their myths and cults. He also studied Asian culture, for the religious symbols and phenomenology of Buddhism and Hinduism and the teachings of Lao-tzu, Confucius, and Zen always had special significance for him. He traveled to India twice, the second time in 1937.

Jung’s most important works appeared in rapid succession, covering everwidening spheres. In addition to psychiatry, he became more and more involved in Greek and other mythologies, patristics and Christian mysticism, gnosis and cabala, and above all alchemy, turning in his later years to modern physics and parapsychology. Everywhere he sought parallels and illuminating insights that provide a deeper understanding of the creative products of the human soul and its eternally recurring basic forms and statements. Above all, however, it was in the symbolism of alchemy and Hermetic philosophy that he found astounding correspondences to the psychic developmental process of the human being. Then there were the important problems of current events, which he treated with an uncanny clearsightedness, thus investing the chaos of our world with new meaning. To the very end his sense for medical problems led him to pursue the targets sighted in his early works: his last paper on schizophrenia (1958a) takes up an old theme, again pointing out the possible physiological etiology of this disease. He strove constantly to penetrate the deeper meaning of delusions and to interpret the material presented in schizophrenia, which is characteristically rich in symbols, and so became one of the champions of the psychotherapeutic approach to the treatment of schizophrenia.

Basic contributions

Only when we survey the nearly two hundred longer and shorter works of Jung do we realize the tremendous scope of the unique pioneering work he accomplished. His writings have been translated into nearly all European languages and into some Asiatic ones. We shall confine ourselves here to listing in brief form some of his most important principles and concepts.

The following concepts are both original and fundamentally significant:

(a) A new formulation of the libido concept, which refers not only to sexuality but to the whole of vital energy, which flows through the psyche in incessant motion, sometimes rising, sometimes diminishing, making possible a functional approach to psychic events.

(b) The concept of the psyche as a self-regulating system, in which the conscious and the unconscious realms are compensatorily related.

(c) The heuristic concept of the unconscious, which distinguishes between the contents of the personal unconscious and the contents of the collective unconscious: the personal unconscious includes material that originates in ontogenesis, and the collective unconscious includes material that originates in phylogenesis, i.e., those patterns of behavior, or actions and reactions of the psyche, that are determined by race and that Jung termed archetypes. They are imperceptible potentialities that manifest themselves as perceptible archetypal patterns and processes (or symbols) only under certain psychic conditions. They occur in man’s dreams, visions, and fantasies and have been expressed in the myths, religious concepts, fairy tales, sagas, and works of art of all epochs and all cultures. Moreover, Jung explicitly stressed the relationship between archetype and instinct.

(d) The concept of the process of individuation,

i.e., of “the evolution of the psyche to its wholeness,” its way of maturing, in which the archetypes appear both as structural elements and as regulators of the unconscious psychic material and constitute particularly dynamic factors. The phases of this process are characterized by the confrontation of the conscious with some typical components of the unconscious realm (shadow, animus–anima, the great mother, the wise old man, the self, etc.). From the perspective of wholeness, which is always kept in mind, both the first and the second halves of life receive their appropriate significance.

(e) The special consideration and development of the religious function of the psyche, which is an integrating element in mental health, its repression and neglect causing psychic disturbances.

(f) The differentiation between two attitude types: the extrovert (oriented toward the external world) and the introvert (oriented to the internal world) and of four functional types, which are characterized by the primacy of thought, intuition, feeling, and sensation respectively.

(g) The interpretation of dreams, using the elements of the subject’s dreams as representations of intrapsychic data, thus gaining insight into the subject’s projections and facilitating the remission of symptoms. In contrast to the causalreductive interpretation of Freud, attention is centered on the future-oriented aspect of unconscious processes.

(Ji) The positive conception of regression in particular and of neurosis in general. Jung gave the latter concept a new content by freeing it from attachment to the biological and instinctual and by giving it, as well as regression, a deeper spiritual sense.

(i)Synchronicity, i.e., the meaningful coincidence of an interior and an external event, as a principle that explains acausal connections, such as presentiments, prophetic dreams, fortuitous events, etc.

(j) The method of active imagination, a stimulation of the symbol-making ability of the psyche to create spontaneous products in which the unconscious contents are concretized in the form of words, musical sounds, painting, drawing, sculpture, dance, etc., and are able to resolve psychic disturbances.

Honors and offices

It is not surprising that these great achievements were appreciated both at home and abroad, earning Jung official positions and honors. Honorary doctorates were conferred on him by Clark, Fordham, Yale, and Harvard universities in the United States; by Oxford in England; by the universities of Calcutta, Benares, and Allahabad in India; and finally by the University of Geneva and the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Jung was awarded the city of Zurich’s literature prize in 1932, and in 1938 he was elected honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine in England. He was made an honorary member of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences in 1944. His academic appointments included the professorship of medical psychology at the University of Basel, which he held for only a brief period because of his health, and the titular professorship of philosophy in the faculty of philosophical and political sciences of the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, 1933–1941/1942.

Jung was elected honorary president of the German Medical Society for Psychotherapy in 1930, and from 1933 to 1939 he was president of the International Society for Psychotherapy, during which time he also edited the international periodical Zentralblatt fur Psychotherapie und ihre Grenzgebiete. He was also chairman of the board of trustees of the Lehrinstitut für Psychotherapie in 1939 and, until his death, of the Swiss Society for Practical Psychology, which he had founded in 1935. In 1948 he founded the bilingual (English and German) C. G. Jung Institute in Zurich, to which he entrusted the continuation and dissemination of his teachings and research and the training in psychotherapy of the new generation.

Jung the man

Justice would not be done to the genius of Jung if we were to try to understand only the scientific and professional aspects of his career. His was an extraordinary personality, combining the keenest contradictions. Contemplativeness and childlike cheerfulness, delicate sensibility and robust simplicity, cold reserve and true devotion, rigor and tolerance, humor and severity, aloofness and love for mankind, were equally prominent traits in his makeup. Except when he was troubled by the birth pangs of a new book, he generously shared his insights and explanations, both in conversation and in letters.

Freud unlocked the door to modern psychical research and psychotherapy. Jung penetrated into the psyche still deeper, shedding light on the impersonal, primeval forces that the twentieth century has confronted with horror and fear. In his untiring effort to solve intractable riddles, he constantly repeated this warning:

I am convinced that exploration of the psyche is the science of the future… This is the science we need most of all, for it is gradually becoming more and more obvious that neither famine nor earthquakes nor microbes nor carcinoma, but man himself is the greatest peril to man, just because there is no adequate defense against psychic epidemics, which cause infinitely more devastation than the greatest natural catastrophes. (Jung 1944)

Jolande Jacobi

[For the historical context of Jung’s work, seePsychoanalysisand the biographies of Bleuler; Freud; Janet. For further discussion of Jung’s ideas, seeAnalytical Psychology. Other relevant information may be found in Dreams; Fantasy; Literature, article on The Psychology Of Literature; Religion.]

WORKS BY JUNG

(1902) 1957 On the Psychology and Pathology of Socalled Occult Phenomena. Pages 3–88 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 1: Psychiatric Studies. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Zur Psychologic und Pathologic sogenannter occulter Phänomene.

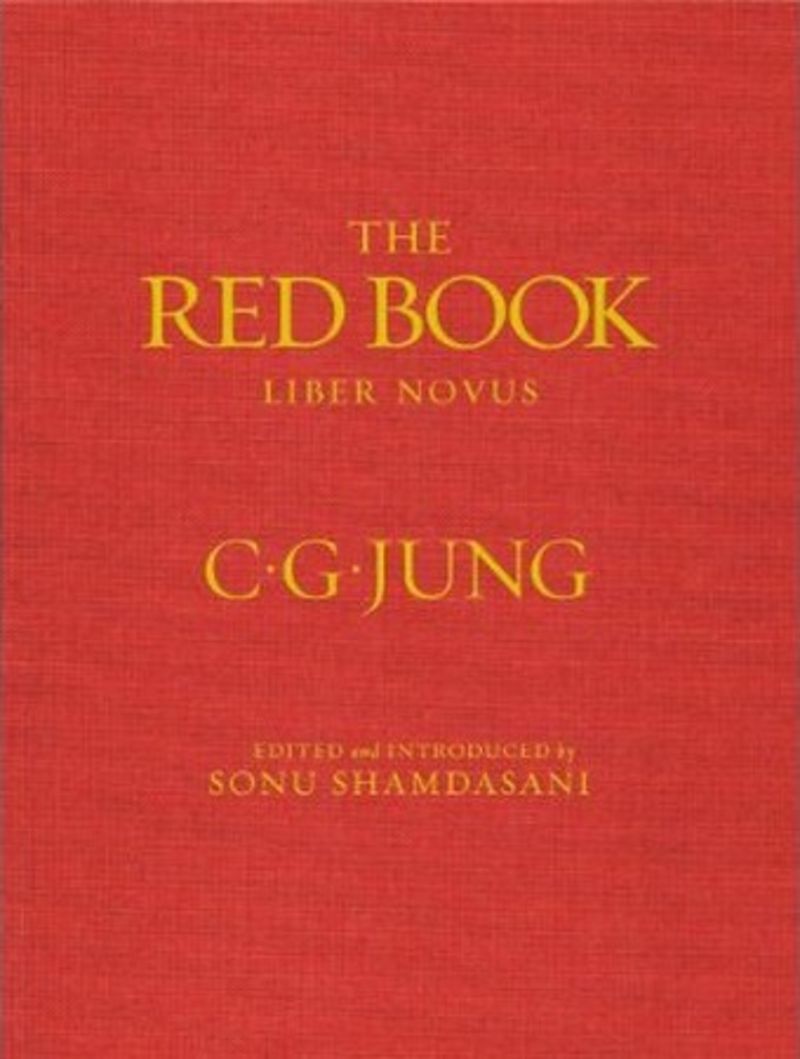

(1902–1959) 1953— Collected Works. Vols. 1— Edited by Herbert Read et al. New York: Pantheon. → Volume 1: Psychiatric Studies, 1957. Volume 3: The Psychogenesis of Mental Disease, 1960. Volume 4: Freud and Psychoanalysis, 1961. Volume 5: Symbols of Transformation, 1956. Volume 7: Two Essays on Analytical Psychology, 1953. Volume 8:The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, 1960. Volume 9, Part 1: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 1959. Volume 9, Part 2: Aion: Researches Into the Phenomenology of the Self, 1959. Volume 10: Civilization in Transition, 1963. Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East, 1958. Volume 12: Psychology and Alchemy, 1953. Volume 14: Mysterium Coniunctionis, 1963. Volume 16: The Practice of Psychotherapy, 1954. Volume 17: The Development of Personality, 1954. Forthcoming volumes include Volume 2: Experimental Researches; Volume 6: Psychological Types; Volume 13: Alchemical Studies; Volume 15: The Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature; and final volumes on his minor works, bibliography, and index.

(1904–1909) 1918 Studies in Word-association: Experiments in the Diagnosis of Psychopathological Conditions Carried Out at the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Zurich, Under the Direction of C. G. Jung. London: Heinemann. → First published as Diagnostische Assoziationsstudien.

(1906) 1941 Die psychologische Diagnose des Tatbestandes. Zurich: Rascher.

(1907) 1960 The Psychology of Dementia Praecox. Pages 1–151 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 3: The Psychogenesis of Mental Disease. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Über die Psychologie der Dementia Praecox: Ein Versuch.

(1909–1946) 1953 Psychological Reflections: An Anthology of the Writings of C. G. Jung. Selected and edited by Jolande Jacobi. New York: Pantheon.

(1910) 1954 Psychic Conflicts in a Child. Pages 8–35 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 17: The Development of Personality. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Über Konflikte der kindlichen Seele.”

(1913) 1961 Theory of Psychoanalysis. Pages 83–226 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 4: Freud and Psychoanalysis. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Versuch einer Darstellung der psychoanalytischen Theorie.

(1916–1945) 1948 Über psychische Energetik und das Wesen der Trädume. Zurich: Rascher. → Contains six essays, all of which appear in translation in Volume 8 of Jung 1902→1959 as The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche.

(1917) 1953 The Psychology of the Unconscious. Pages 1–117 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 7: Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Die Psychologic der Unbewussten Prozesse.

(1921) 1959 Psychological Types. London: Routledge. → First published as Psychologische Typen.

(1922–1931) 1959 Modern Man in Search of a Soul. London: Routledge. → First published as Seelenprobleme der Gegenwart.

(1926) 1954 Analytical Psychology and Education: Three Lectures. Pages 65→132 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 17: The Development of Personality. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Analytische Psychologic und Erziehung.

(1928) 1953 The Relations Between the Ego and the Unconscious. Pages 119–239 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 7: Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Die Beziehungen zwischen dem Ich und dem Unbewussten.

(1929) 1962 Commentary. Pages 77–137 in T’ai i chin hua tsung chih, The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book of Life. New York: Harcourt. → First published as “Europäischer Kommentar.”

(1929–1934) 1947 Wirklichkeit der Seele: Anwendung und Fortschritte der neueren Psychologic. Zurich: Rascher.

(1930–1940) 1950 Gestaltungen des Unbewussten. Zurich: Rascher.

(1932) 1958 Psychotherapists or the Clergy. Pages 325–347 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Die Beziehungen der “Psychotherapie zur Seelsorge.

(1935) 1958 Psychological Commentary on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Pages 509–526 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Psychologischer Kommentar zum Bardo ThÖdol”

(1935–1947) 1954 Von den Wurzeln des Bewusstseins: Studien Über den Archetypus. Zurich: Rascher.

(1936–1945) 1946 Aufsätze zur Zeitgeschichte. Zurich: Rascher.

(1938) 1958 Psychology and Religion. Pages 3–105 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. New York: Pantheon. → First published in English.

(1940) 1959 The Psychology of the Child Archetype. Pages 151–181 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 9, Part 1: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Zur Psychologic des KindArchetypus.”

(1941) 1959 The Psychological Aspects of the Kore. Pages 182–203 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 9, Part 1: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Zum psychologischen Aspekt der Kore-Figur.”

1942 Paracelsica: Zwei Vorlesungen über den Arzt und Philosophen Theophrastus. Zurich: Rascher.

(1942–1946) 1953 Symbolik des Geistes: Studien über psychische Phdnomenologie. Zurich: Rascher.

(1943) 1954 The Gifted Child. Pages 135–145 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 17: The Development of Personality. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Der Begabte.”

(1944) 1962 Epilogue. In Carl Gustav Jung, L’homme à la découverte de son âme. 6th ed. Geneva: Éditions du MontBlanc.

(1946) 1954 Psychology of the Transference. Pages 163–321 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 16: The Practice of Psychotherapy. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Die Psychologic der Übertragung.

(1952 a) 1958 Answer to Job. Pages 355–470 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Antwort auf Hiob.

(1952 b) 1960 Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. Pages 417–519 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 8: The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Synchronizitat als ein Prinzip akausaler Zusammenhänge.”

(1957) 1963 The Undiscovered Self (Present and Future). Pages 245–305 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Gegenwart und Zukunft.

(1958 a) 1960 Schizophrenia. Pages 256–271 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 3: The Psychogenesis of Mental Disease. New York: Pantheon. → First published in German.

(1958 b) 1963 Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth. Pages 307–433 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. New York: Pantheon. → First published as Ein moderner Mythos: Von Dingen, die am Himmel gesehen werden.

(1958 c) 1963 A Psychological View of Conscience. Pages

437–455 in Carl Gustav Jung, Collected Works. Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. New York: Pantheon. → First published as “Das Gewissen in psychologischer Sicht.”

SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abler, Gerhard 1948 Studies in Analytical Psychology. New York: Norton.

Clark, Robert Alfred 1953 Six Talks on Jung’s Psychology. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Boxwood.

Fordham, Michael 1957 New Developments in Analytical Psychology. London: Routledge.

Fordham, Michael (editor) 1963 Contacts With Jung: Essays on the Influence of His Work and Personality.London: Tavistock.

Glover, Edward (1950) 1956 Freud or Jung? New York: Meridian.

Harding, M. Esther 1948 Psychic Energy: Its Source and Goal. With a foreword by C. G. Jung. New York: Pantheon.

Jacobi, Jolande (1940) 1951 The Psychology of C. G. Jung. Rev. ed. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. → First published in German. A paperback edition was published in 1962 by the Yale University Press.

Jacobi, Jolande (1957) 1959 Complex, Archetype, Symbol in the Psychology of C. G. Jung. New York: Pantheon. → First published in German.

Jacobi, Jolande 1966 The Way to Individuation. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Jung Institut, Zurich 1955 Studien zur analytischen Psychologie C. G. Jungs. 2 vols. Zurich: Rascher.

Progoff, Ira 1953 Jung’s Psychology and Its Social Meaning. New York: Julian.